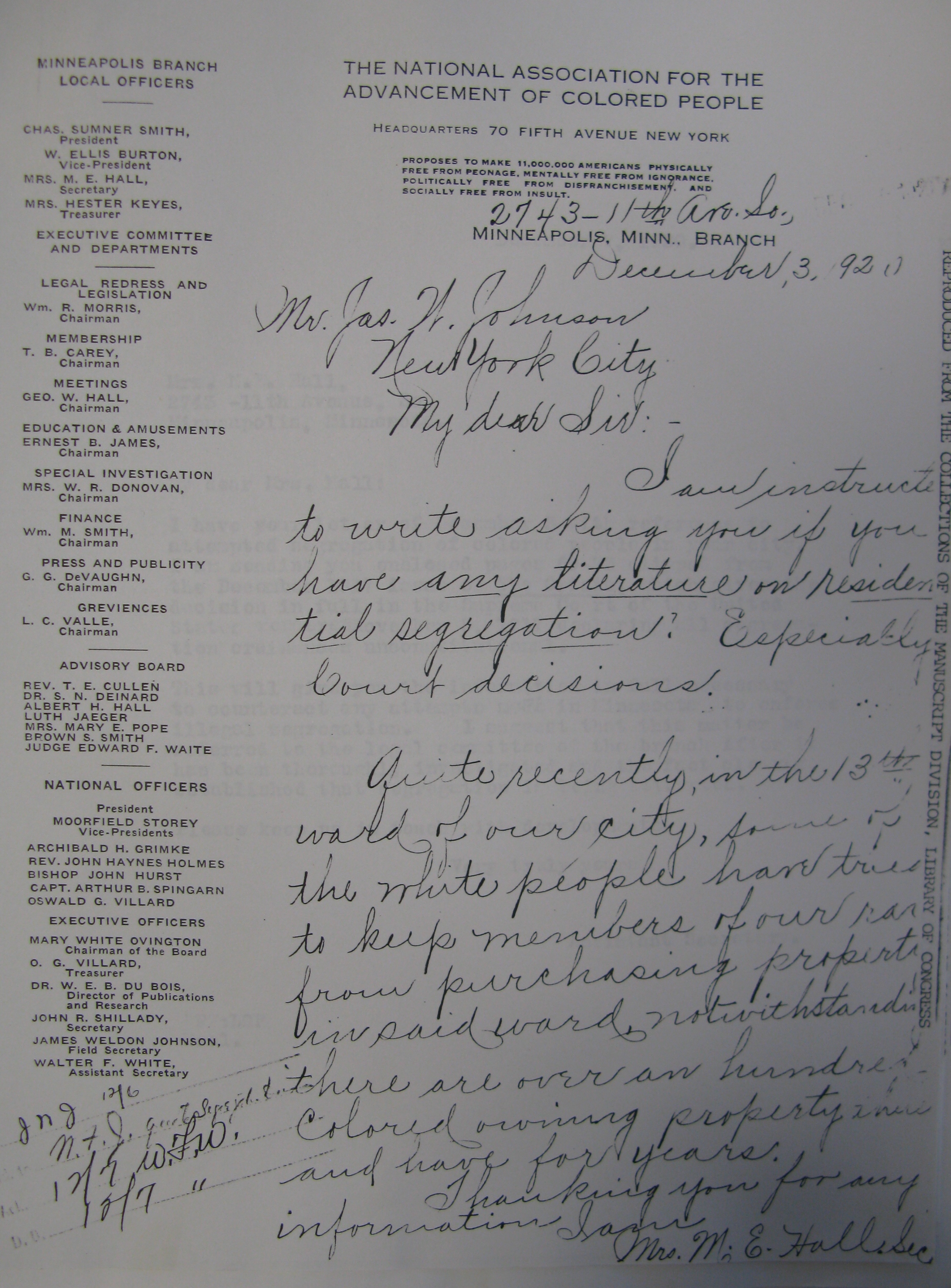

On December 3, 1920, the Secretary of the Minneapolis branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People penned a letter to her organization’s headquarters in New York City. She was writing to request any literature available on “residential segregation. Especially court decisions.”

Two weeks earlier, this small chapter of the national civil rights organization had watched, with dismay as 200 residents of South Minneapolis gathered at a community center on 43rd and Pillsbury Avenue South. The meeting was convened to protest “against the presence of Negroes or persons of Negro blood, as residents in the Thirteenth Ward,” according to the Minneapolis Morning Tribune article enclosed in the letter. Mrs. Hall elaborated on the situation for her New York correspondent. “White people,” she wrote in the letter above, ” have tried to keep members of our race from purchasing property in said ward, notwithstanding there are over an hundred colored owning property and have for years.”

Neighbors were agitated over falling real estate prices, which they blamed on an influx of African Americans. These activists had no way to know that Minneapolis had entered what would be perhaps the longest economic decline in the city’s history. Triggered by the collapse of farm commodities at the end of World War I, this slump would only deepen through the Great Depression. It would be more than two decades–after the end of World War II–before the city’s economy would revive.

In 1920, white Minneapolitans could not discern these larger economic trends. Instead, they focused their anxiety on what they saw as an obvious causal relationship between sinking real estate values and a burgeoning African American community. The newcomers had arrived in the city as part of the larger Great Migration, which brought massive numbers of African Americans out of Jim Crow peonage in the South to Northern cities. For these migrants, Minneapolis never had the allure of Chicago or Detroit or New York, largely because job prospects were so grim for African Americans in the Mill City. But the city had difficulty absorbing even this small number of opportunity seekers, who settled in the most overcrowded and crumbling sections of town. Their quest for housing was circumscribed by the hostility of neighborhood groups like the one that emerged at 43rd and Pillsbury.

At the meeting on Pillsbury, neighbors appointed a committee of 12 to “make a check on the number of residents with colored blood and ascertain who had sold the property to them.. .The aim, as set forth in the meeting, is to prevent others from buying real estate, and to negotiate with those who are now residents, seeking their change of residence,” according to the Morning Tribune.

One member of this committee declared that “they know they are undesirable as neighbors and hope to make a great profit on their investment by forcing white people to buy them out to get rid of them.”

Mrs. Hall got only a terse reply from New York, which included a clipping from the NAACP’s publication The Crisis. This article, according to the staff member who fielded her request, “gives the decision in full in the Supreme Court of the United Sates rendered Nov. 5, 1917 declaring all segregation ordinances unconstitutional.” The law was clear. Cities could not prohibit African Americans from buying property in any neighborhood. But of course–as this and other neighborhood campaigns showed –Hall and other civil rights activists risked the wrath of the mob if they dared to transgress the often invisible racial boundaries laid across the urban landscape.

The newspaper quotes are from the Minneapolis Morning Tribune. The letter reproduced above is from the NAACP archival collection at the Library of Congress. It comes to me via Professor Ann Juergens, of the William Mitchell College of Law, who shared this document and so much more from her pathbreaking research on civil rights pioneer Lena Olive Smith.