It’s Map Monday. And it’s Indigenous Peoples Day in Minneapolis, which has adopted this new celebration to replace the long-controversial commemoration of Columbus Day.

With one of the largest urban communities of Native Americans in North America, Minneapolis has been a long-time center for indigenous activism. And it was these activists who convinced the City Council earlier this year to scrap Columbus Day, which has been under attack for years as racist tribune to the brutal colonization and dispossession of the Native peoples of North America.

Indigenous Peoples Day seeks to recognize the history of American Indians in the city. Ojibwe people began migrating to Minneapolis in large numbers during World War II, when war industries offered the prospect of steady employment for impoverished rural dwellers. These migrants made the city’s Phillips neighborhood–with its commercial corridor along Franklin Avenue– a national center for Indian life.

These new Minneapolitans built community through a network of institutions designed to help newcomers find jobs, housing, healthcare, education and social support in a city that was often hostile to Indians. Notable among these early groups was the Upper Midwest American Indian Center, which in 1961 became a center for these mutual aid efforts. In 1975, the Minneapolis American Indian Center opened on Franklin Avenue, the physical epicenter of the urban Indian community.

Most famously, in 1968 the city became the birthplace of the American Indian Movement, which mounted a frontal assault on institutionalized racism. According to founder Dennis Banks, AIM sought to challenge the city’s law enforcement and civil authorities which used the “prisons, courts, police, treaties” to create a brutal environment of oppression for Native Americans.

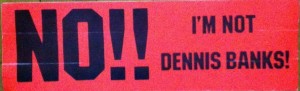

From its beginnings in south Minneapolis, AIM quickly grew into a national organization and is credited with fundamentally reshaping popular understandings of indigenous peoples. Its avowedly revolutionary agenda–and its repudiation of non-violence–also made it one of the most feared organizations of its time. This militancy prompted intensified surveillance of Native Americans, especially those in Minneapolis. Activists responded to harassment from local and federal authorities by printing this bumper sticker:

This political artifact came to me from the personal collection of Native American scholar and activist David Beaulieu, who explained that “No! I’m Not Dennis Banks” was meant to be a humorous rejoinder to police harassment. In pursuit of AIM leaders, police worked from the assumption that all Native Americans looked alike and that all Indians in the city were part of a violent revolutionary conspiracy. The bumper sticker was meant to protest the police practice of stopping all Native American motorists.

While the 1970s was a dramatic period for Native Americans in the city, this history stretches much further into the past. Long before this urban Indian community took shape, “long before the white man ever dream of our existence, the Dakota roamed this land,” Wanbdi Wakiya has written. The Dakota hunted and fished; collected maple sugar and harvested wild rice on the land that became Minneapolis for centuries before the United States established its military outpost at Fort Snelling in 1819.

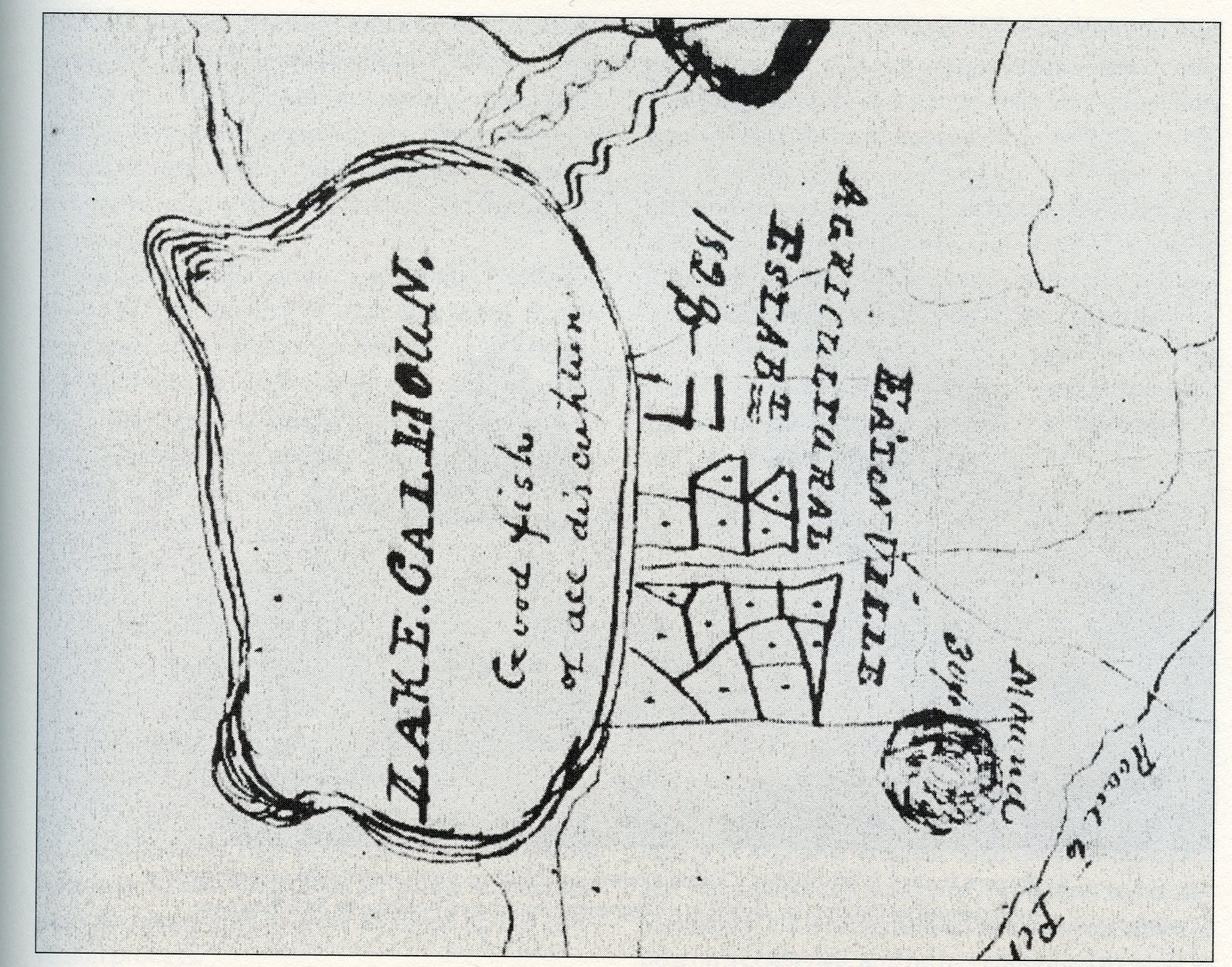

In the 1830s, a small band of Dakota led by Cloud Man established an innovative new settlement that sought to integrate American agricultural practices into Dakota lifeways. Drawn by Indian agent Lawrence Taliferro, this map featured above shows this settlement–the village of Heyate Otunwe, “the village at the side” that was located on the east side of Lake Calhoun. Taliaferro’s hand labeled it as “Eatonville Agricultural Estab. 1828.” It was at this village that the Dakota language was first systematically recorded on paper by missionaries Samuel and Gideon Pond, who sought to translate the Bible into Dakota. Though this agricultural experiment was successful in many ways, the village was abandoned in 1839. Hostilities between the Ojibwe and Dakota had flared and inhabitants feared that the location made them too vulnerable to attack.

The rich story of Indians in Minneapolis has recently become the focus of a new initiative undertaken by Migizi Communications and Laura Waterman Wittstock, who is researching both government policies and material conditions that shaped the experience of Native American migrants to the cities in the period after World War II. Check out this group’s Facebook page, which shares tidbits from their research each week. And check out the celebration at the Minneapolis American Indian Center later today. The event will feature food, poetry, dance performances and speeches. Speakers will include former vice presidential candidate Winona LaDuke, Minneapolis mayor Betsy Hodges, U.S. Senator Al Franken and U.S. Representative Keith Ellison.

Sources for this post include Brenda J. Child, Holding our World Together; Julie L. Davis, Survival Schools; Mni Sota Makoce: The Land of the Dakota, Gwen Westerman and Bruce White, eds. The bumper stickers is from the private collection of David Beaulieu. The quote from Wanbdi Wakiya is from Mni Sota Makoce. The map–originally drawn by Lawrence Taliaferro and in the collection of the Minnesota Historical Society– was reproduced here from the essay by Katherine Beane in Mni Sota Makoce.