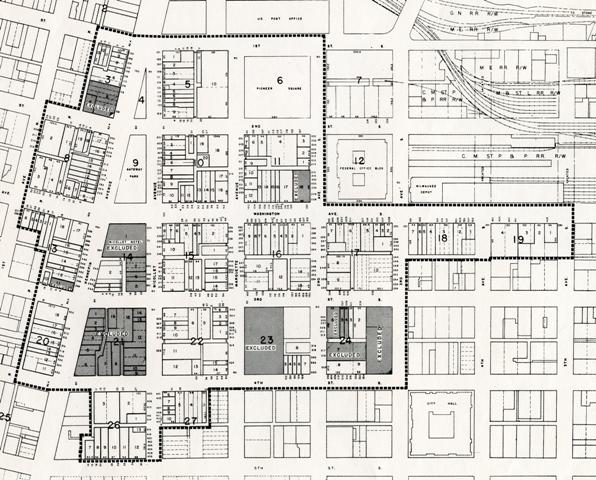

It’s map Monday. Today we have a diagram that shows the Gateway redevelopment project, a massive urban renewal effort that bulldozed a large chunk of downtown Minneapolis in the mid-twentieth century. This project opened a new era for Minneapolis and the nation. The largest urban renewal attempted in the United States until this point, it prompted wide scale demolition that left scars on the city that are only beginning to heal.

The parcels marked in dark gray on this map were “excluded” from the demolition, which began in 1959 and continued for five years. One of the surviving properties was the Nicollet Hotel, which received a dispensation from city planners. On the eve of the redevelopment effort, the hotel was purchased by a national chain. The building remained standing until 1991.

Over the last year, the “Nicollet Hotel” site has garnered intense scrutiny. After a series of failed efforts to construct a transit hub on this site, planners solicited proposals to develop what Council member Jacob Frey called “the sexiest parcel in the city.” City leaders revealed last week that they favored a plan by United Properties to erect a 36-story tower. In a nod to history, this new development will be called “The Gateway.”

The flashy skyscraper envisioned has little in common with the nineteenth century streetscape that disappeared under the wrecking balls of the 1950s. But the name hearkens back to an earlier period for this neighborhood, which had one of the liveliest streetscapes in the city.

For more than a century, city leaders have struggled to engineer what they believed to be the right mix of street life for this section of town. One of the main goals of this current proposal is to return pedestrians to an area now largely deserted by dark. But for the first half of the twentieth century, city leaders were exasperated by what they believed to be a surfeit of people on the street, after the historic heart of the city became the region’s largest skid row.

The “Gateway” development envisioned by United Properties is supposed to connect Nicollet Mall to the Mississippi River. In contrast, when the Nicollet Hotel was erected by a group of civic-minded businessmen in 1924, it was designed to wall off the “blighted” section of the city from its upscale shopping district. The hotel resembled a fortress, with high brick walls that towered over Gateway Park.

Gateway Park and Nicollet Hotel. Postcard collection. Special Collections Department, Hennepin County Libraries.

When the Nicollet Hotel was constructed, the adjoining park and its Beaux Arts pavilion were new. But the park had already become a gathering spot for residents of the surrounding skid row. City leaders dismissed these men as “loafers” and “undesirables,” ignoring the fact that they had labored for decades in seasonal industries before their bodies and the economy had changed. They no longer had the stamina or the opportunity to work in logging camps or on harvest gangs. Their lives became circumscribed by the neighborhood, which offered bars, cage hotels, missions

and cheap restaurants to meet their modest needs.

The Gateway renewal plan that emerged at the end of World War II sought to “increase the quantity and quality of people coming to the [Lower Loop or Gateway],” according to the 1956 Downtown Council. City leaders agreed that it was no longer enough to wall off the Gateway from the rest of the city. They called for its destruction, casting it as a diseased limb that threatened the body of the entire community. Only in this way could planners “restore the health of the city,” one report from the 1950s claimed, “in much the same way personal health might be restored by removing a clot from the bloodstream.”

City leaders are ebullient about this new “Gateway.” If this plan can deliver–succeeding after more than a century of city planning has fallen short–it will be a true watershed for the city.