It’s map Monday. And it’s also women’s history month.

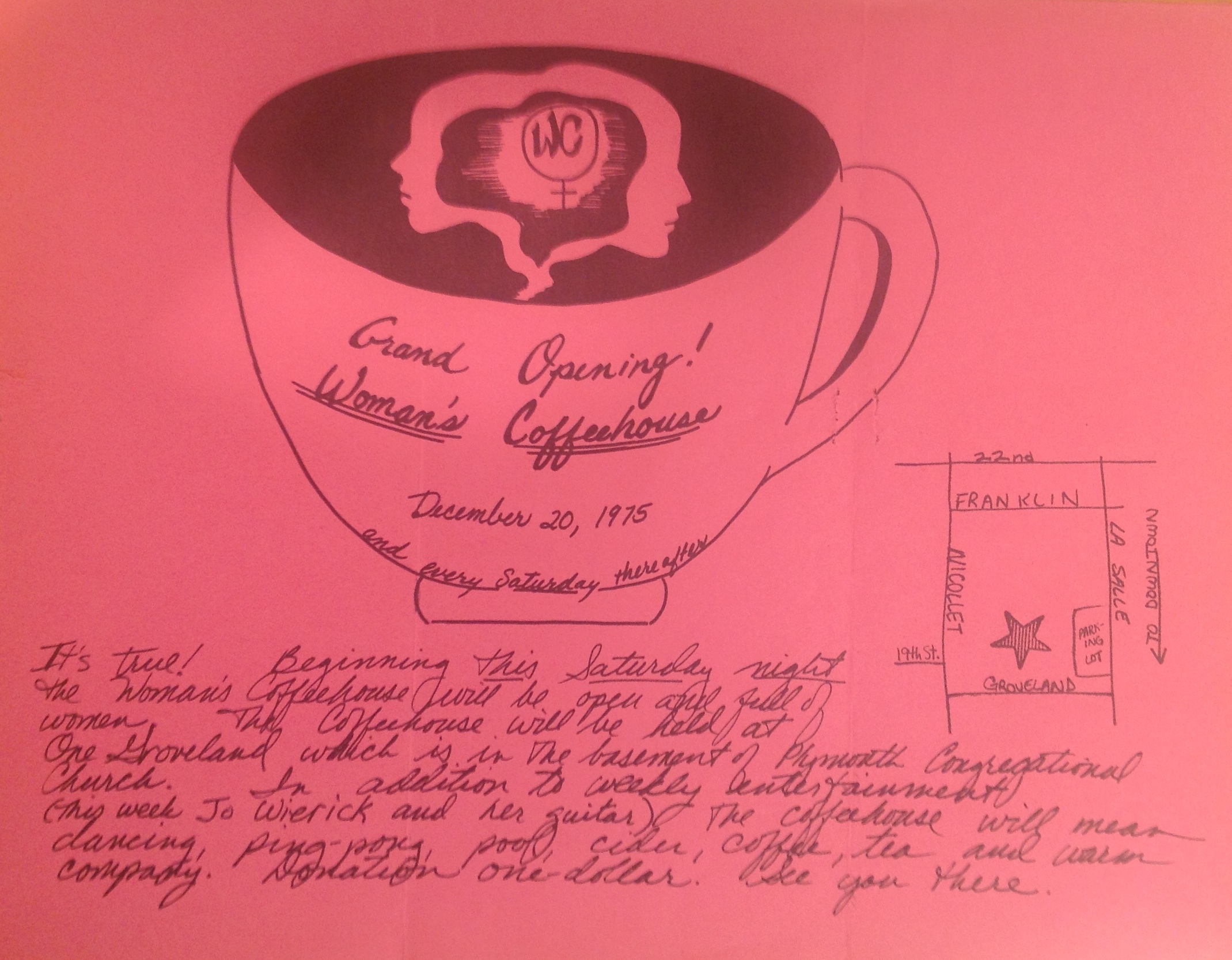

This 1975 flier features a hand-drawn map directing readers to the “Grand Opening” of the “Women’s Coffeehouse” in the basement of Plymouth Congregational Church. Until it closed its doors in September of 1989, the Coffeehouse was the “most celebrated and notorious of feminist institutions in Minneapolis,” according to historian Finn Enke. Coffeehouse founder Candace Margulies later recounted to Enke: “Imagine: two or three times a week hundreds of predominantly lesbian women gathering for workshops, political organizing, dances and concerts, in a church! It was like you had died and gone to lesbian heaven!”

While it attracted lesbians from all over the region, the Coffeehouse never used the word “lesbian” in its promotional material, which emphasized that it was “Open to all Women.” Its vision for a safe and sexually liberating space drew women to the basement of Plymouth Congregational Church for fourteen years before the Coffeehouse collapsed in internecine politics.

The weekly gatherings–and the collective that organized them–quickly became a hub for the national women’s liberation movement. Its performers, speakers and newsletters connected Minneapolis women to activists, causes and ideas from around the country. The collective organized diverse programming, gathering women on Friday and Saturday nights to hear emerging artists from the world of lesbian comedy and women’s music. Coffeehouse participants did workshops on auto repair, women’s health and socialism.

Conceived as a “chemical-free” alternative to the bar scene, the Coffeehouse became a center for all kinds of radical politics. While the group was dominated by white, middle-class women, the Coffeehouse collective sought connections to the city’s swelling American Indian Movement, finding common cause in an adversarial relationship with the FBI. Federal law enforcement kept both feminists and red power activists under constant surveillance in these years. The Coffeehouse raised funds for Native American child custody battles and the legal defense of activists behind the AIM occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota.

And every night they convened, at the conclusion of the political program, the women at the Coffeehouse danced. They found liberation in moving their bodies, late into the night, in a space with only women, free from harassment and fear.

Mixing dancing and politics was a hallmark of women’s liberation, which anointed early twentieth century feminist and anarchist Emma Goldman as one of their greatest heroines. One of the rallying cries of the movement was a quote attributed to Emma Goldman: “If I can’t dance I don’t want to be in your revolution.” In truth, this line was a paraphrase rather than a quote. Goldman’s actual rebuff of a comrade who condemned her dancing was less pithy. “I want freedom, the right to self-expression, everybody’s right to beautiful, radiant things,” Goldman declared in her 1931 autobiography.

This was the spirit that animated the Coffeehouse Collective. These women liberationists wanted to dance and debate; to find joy as well as justice. And they did–at the intersection of Groveland and Nicollet, on the edge of downtown Minneapolis–for more than a decade.

Flier is from the Coffeehouse Collective records at the Minnesota Historical Society. Thanks to Finn Enke for her wonderful analysis of the Coffeehouse Collective in Finding the Movement: Sexuality, Contested Space and Feminist Activism (2007: Duke University Press).