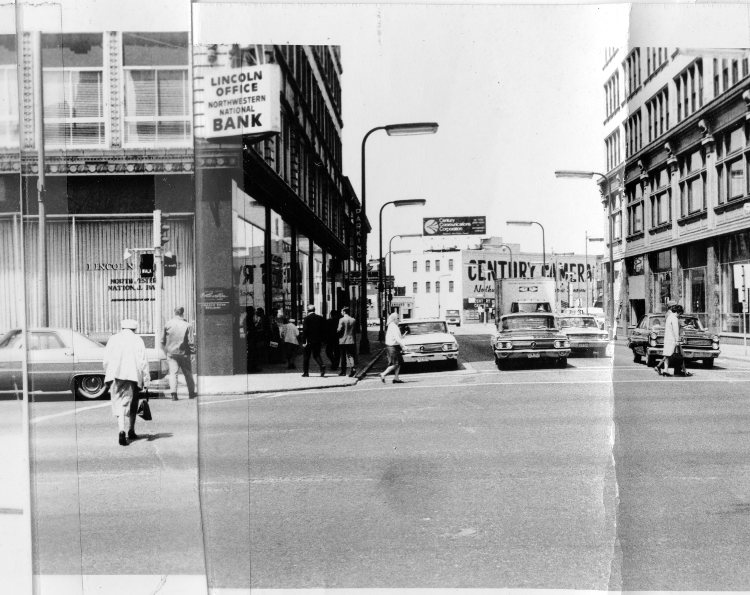

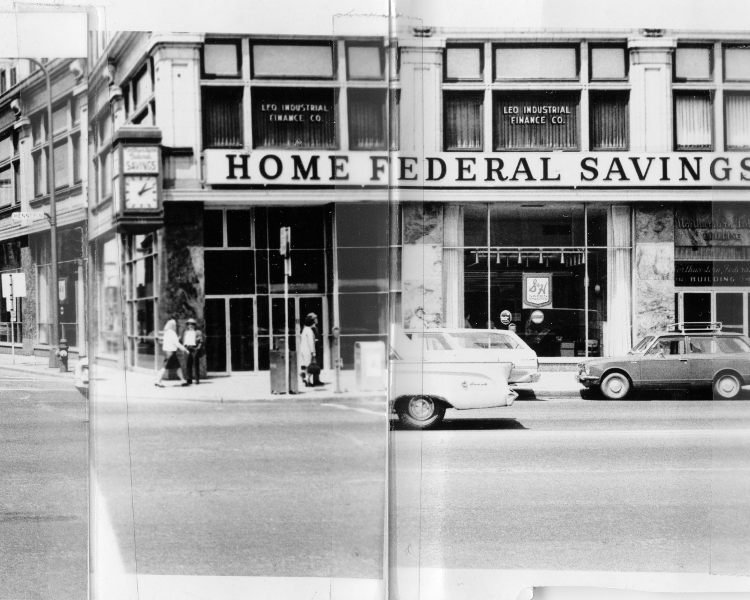

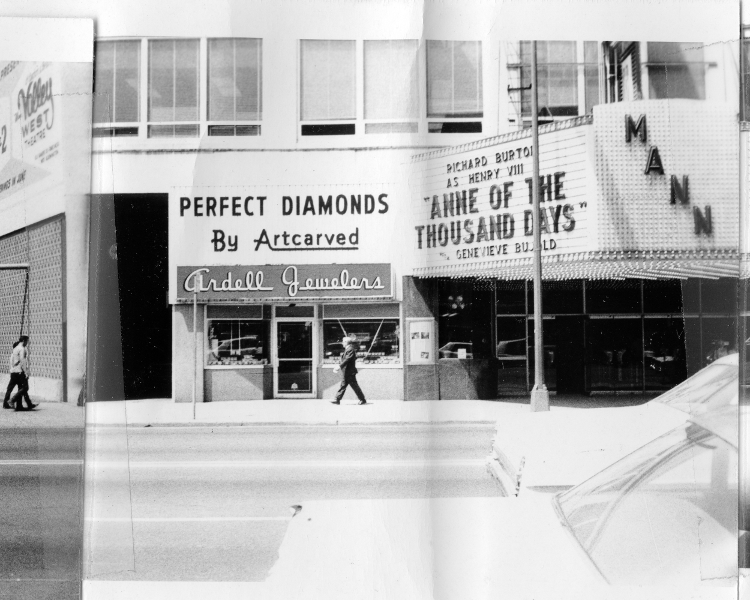

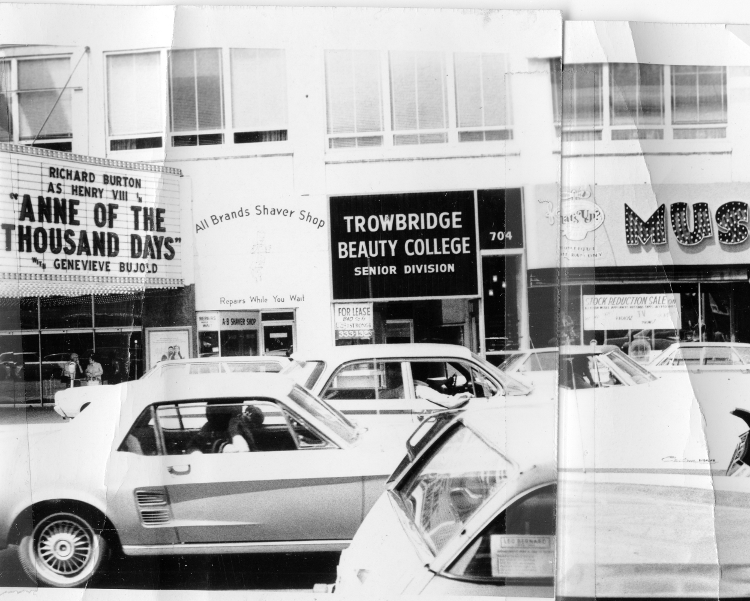

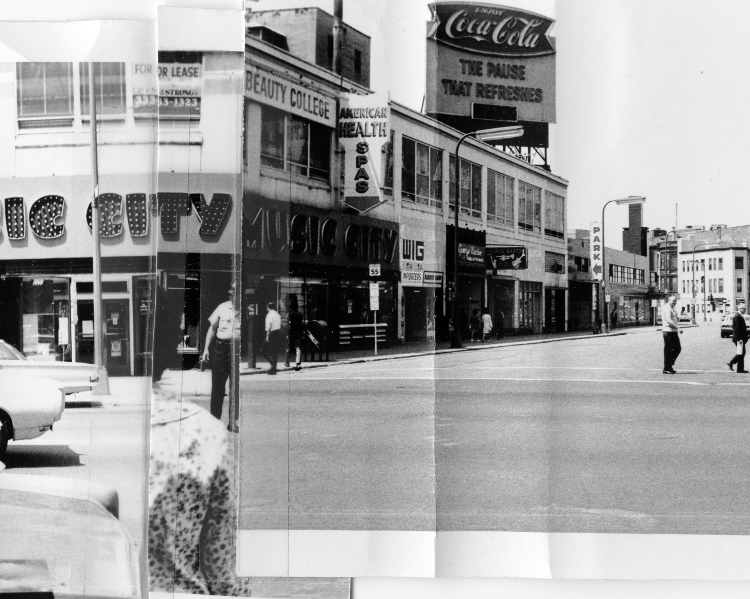

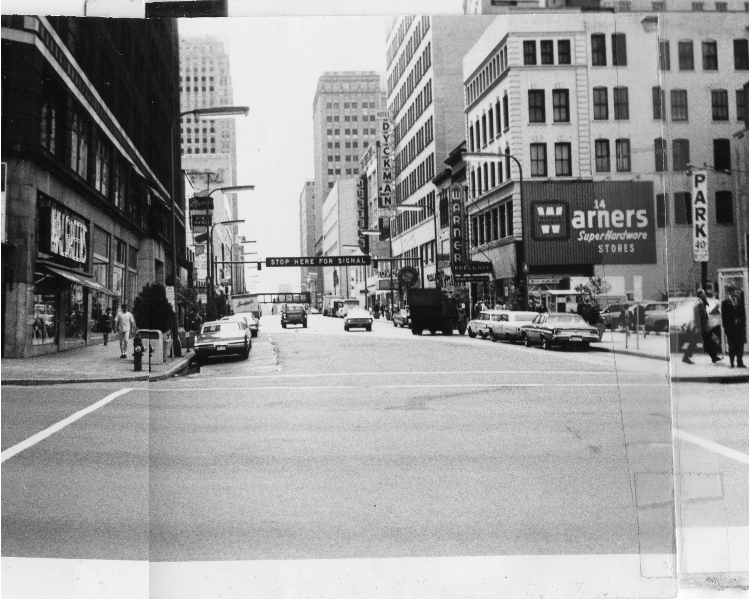

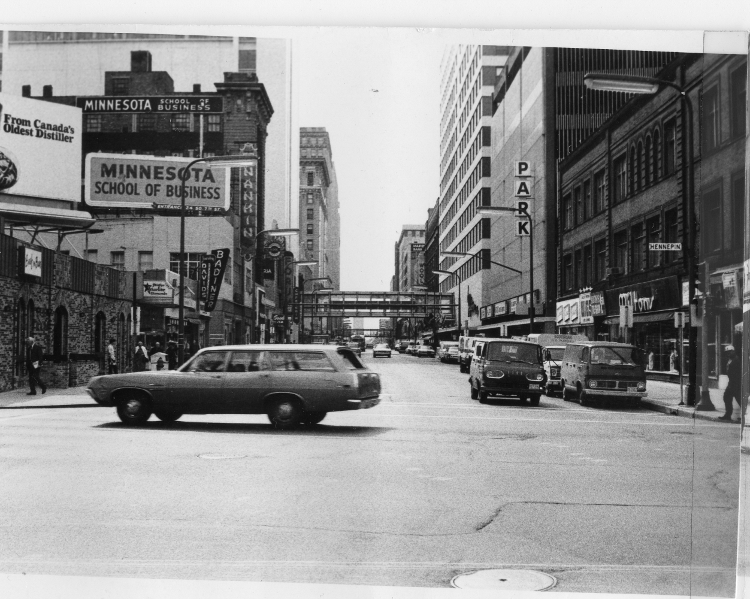

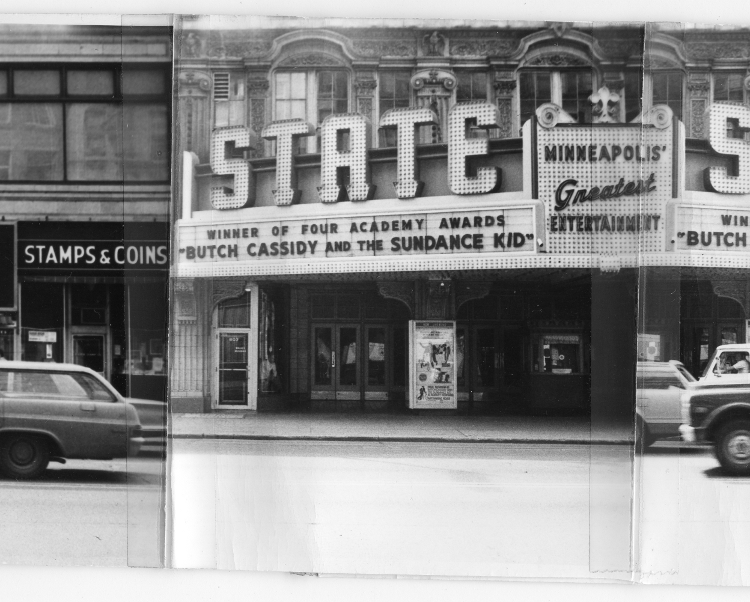

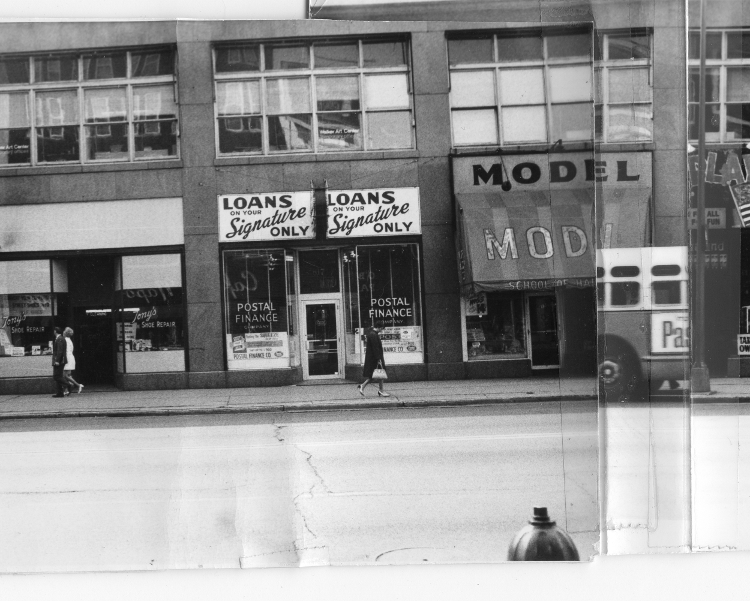

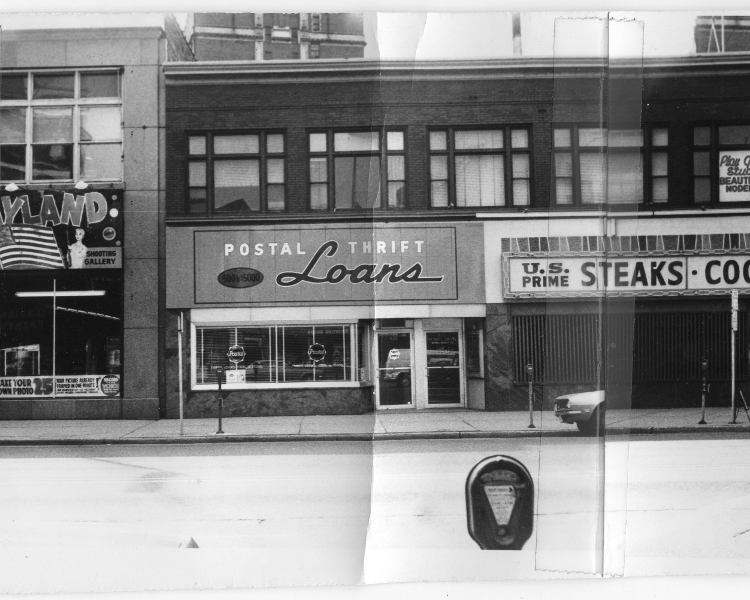

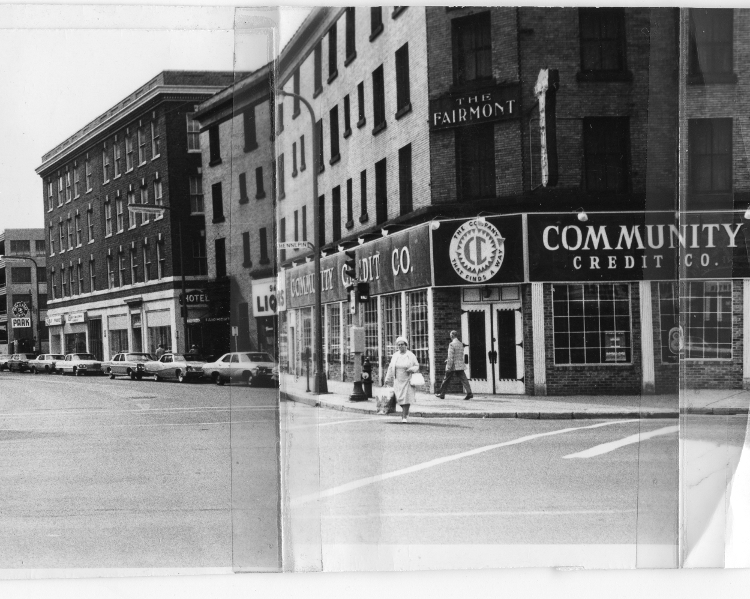

Washington Avenue between First and Nicollet. Click on the image to start the interactive tour.

This Washington Avenue “now-and-then visualization” was designed and engineered by Historyapolis intern Kevin Ehrman-Solberg, who curated the historic images and took the current-day photos of the street. The text for the post was co-written by Kevin Ehrman-Solberg and Kirsten Delegard.

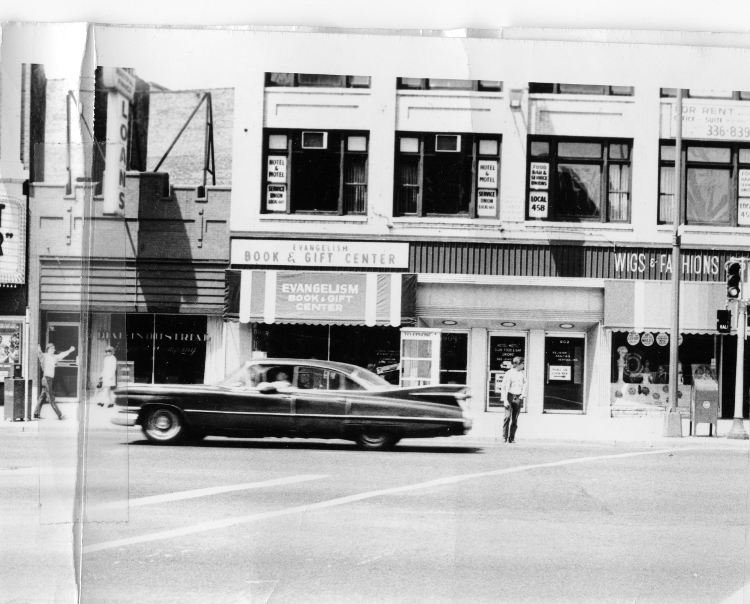

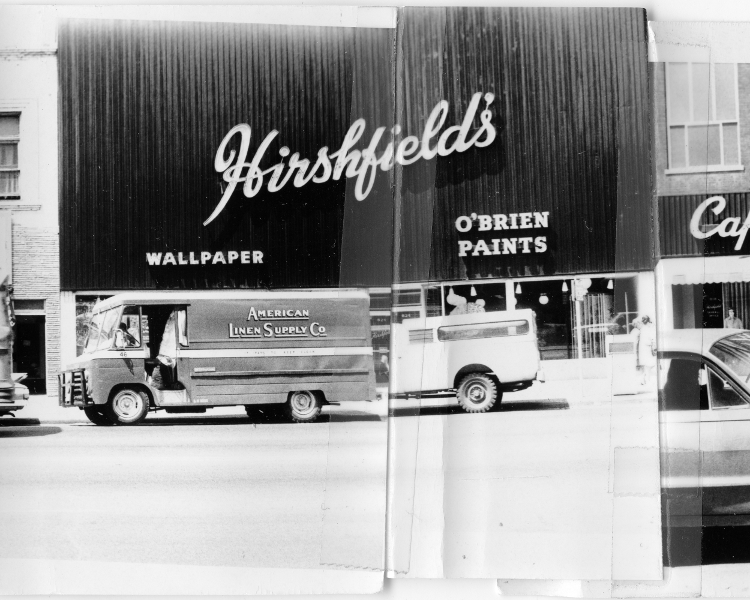

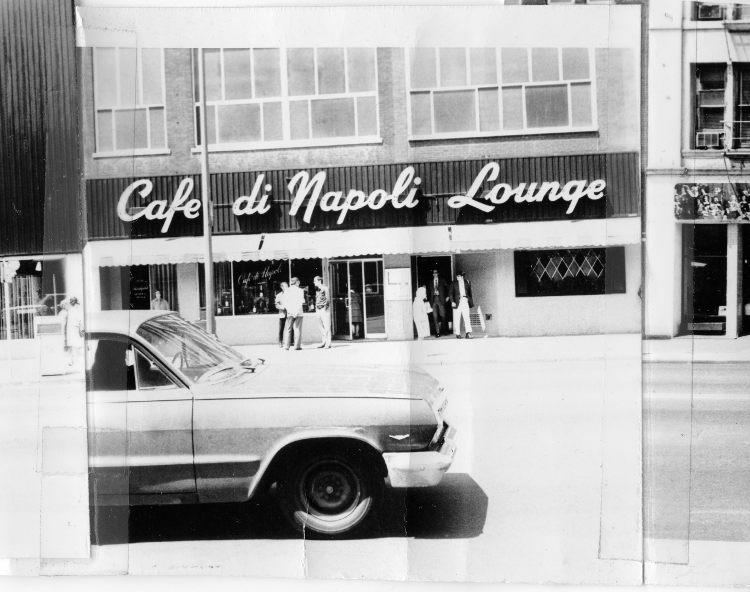

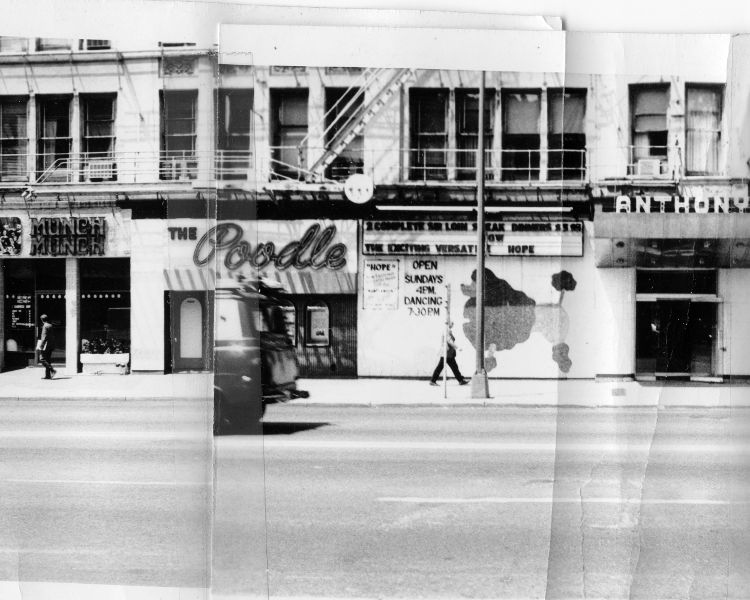

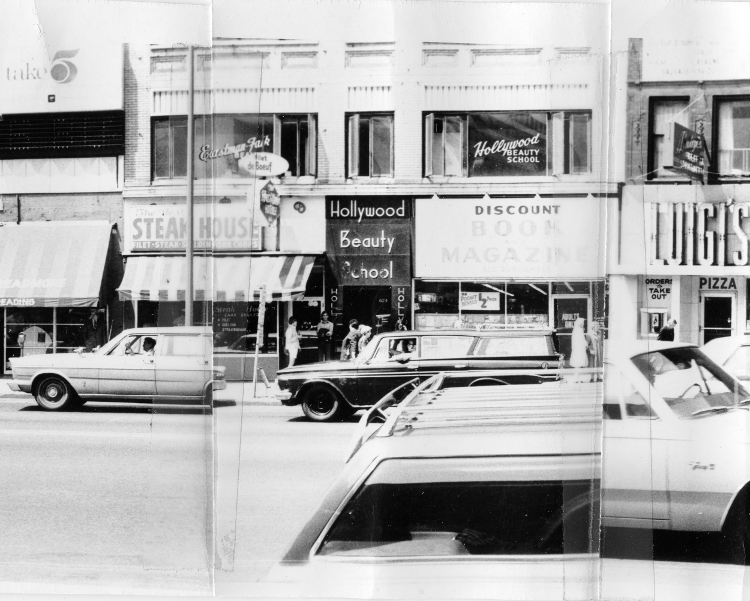

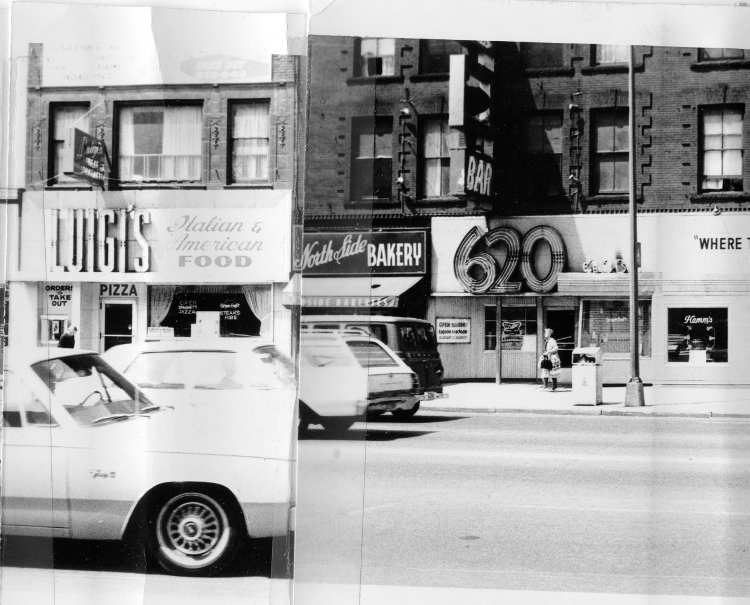

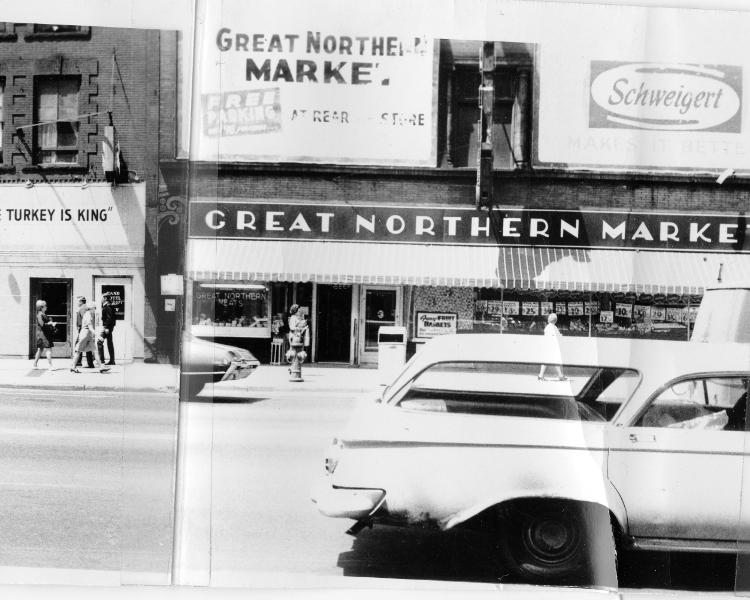

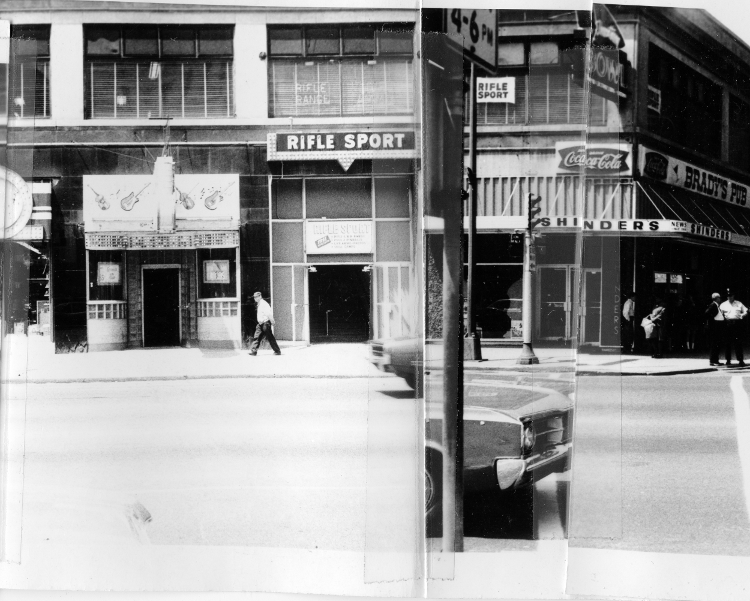

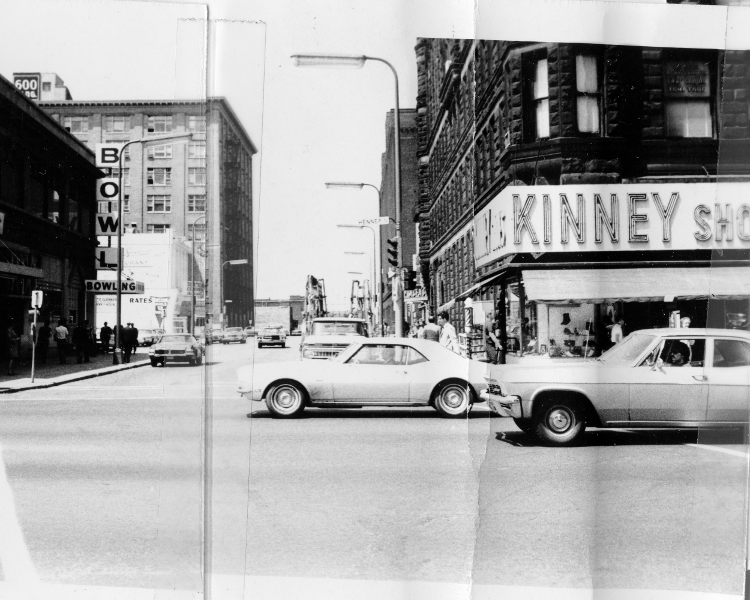

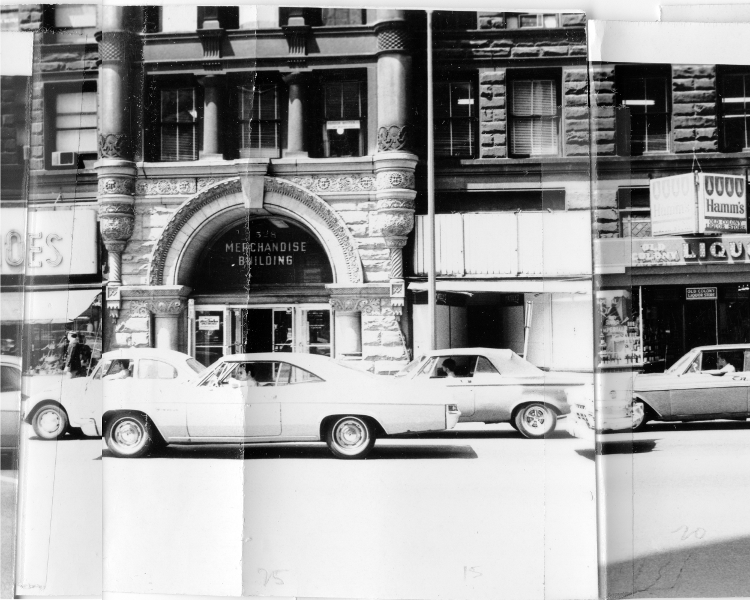

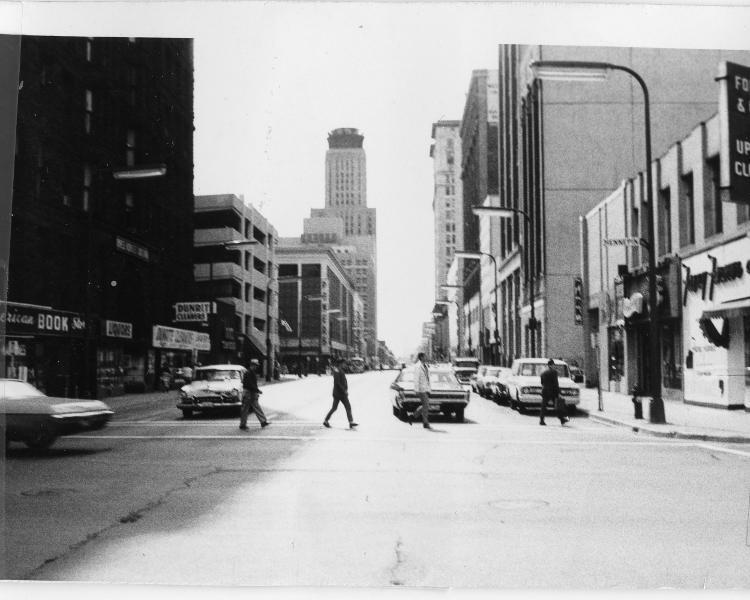

Few streets in Minneapolis have a past so checkered as Washington Avenue. An important commercial artery during the boom years of the 1880s, the street today is again at the center of a building boom. This digital exhibit uses visuals to compare one version of its nineteenth century facade to the present streetscape.

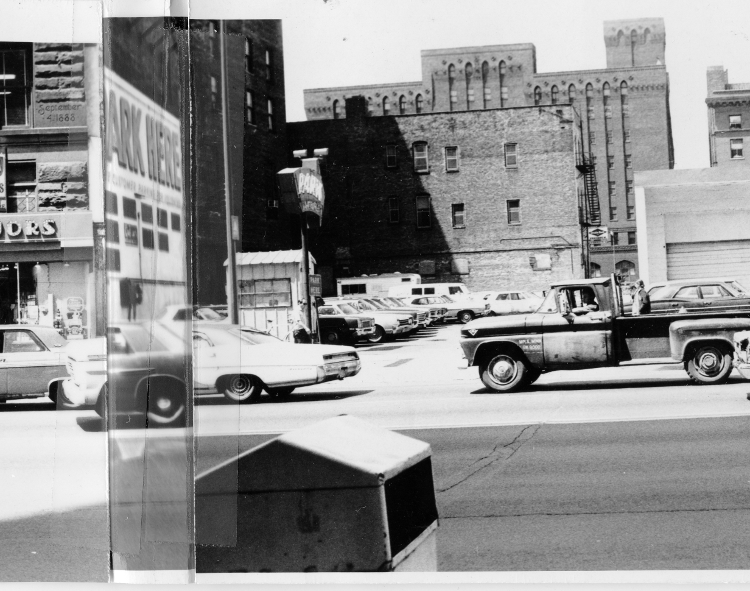

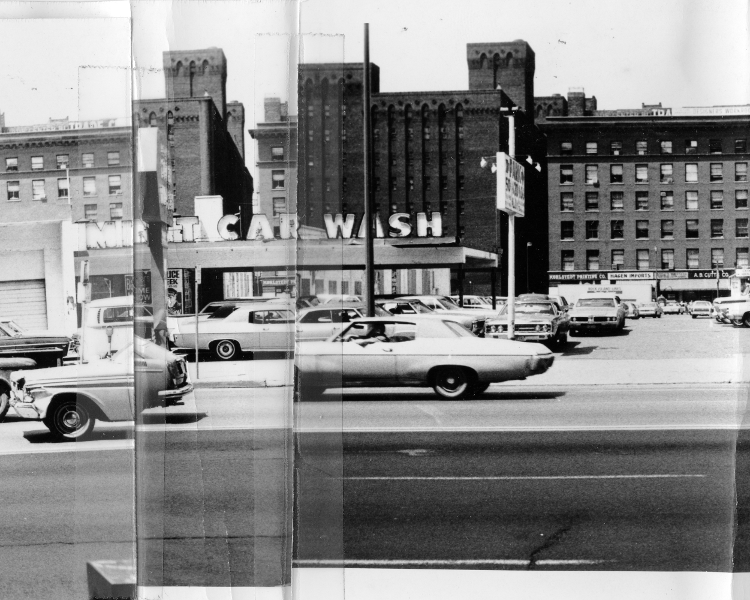

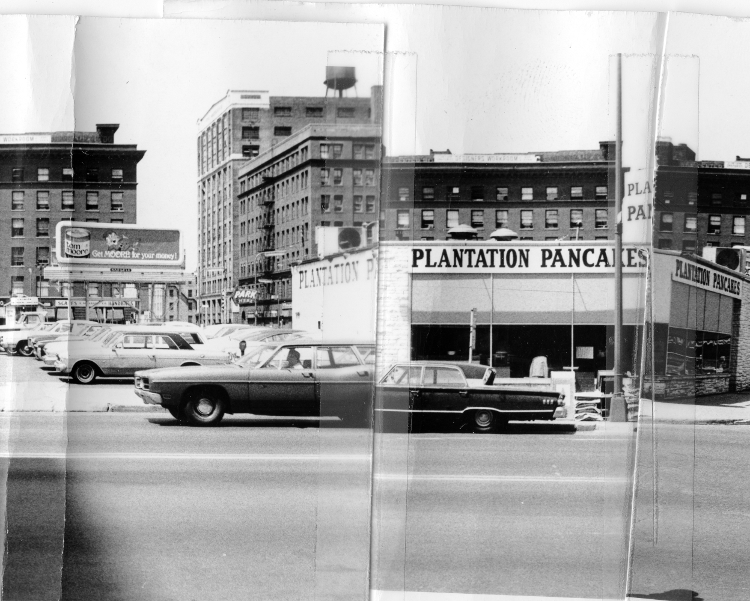

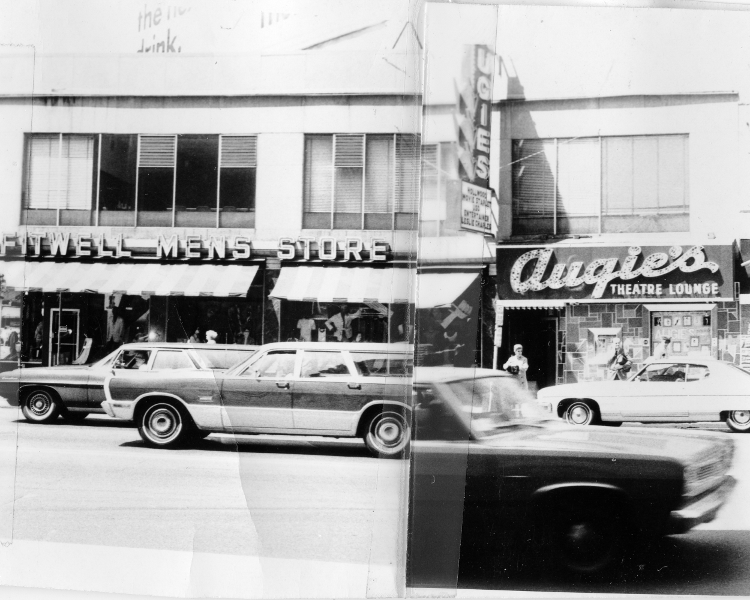

This digital juxtaposition—which you can view here— shows the complete transformation of Washington Avenue over the last 130 years. Yet these paired images also obscure as much as they reveal, glossing over the turbulent history of one of the city’s original thoroughfares.

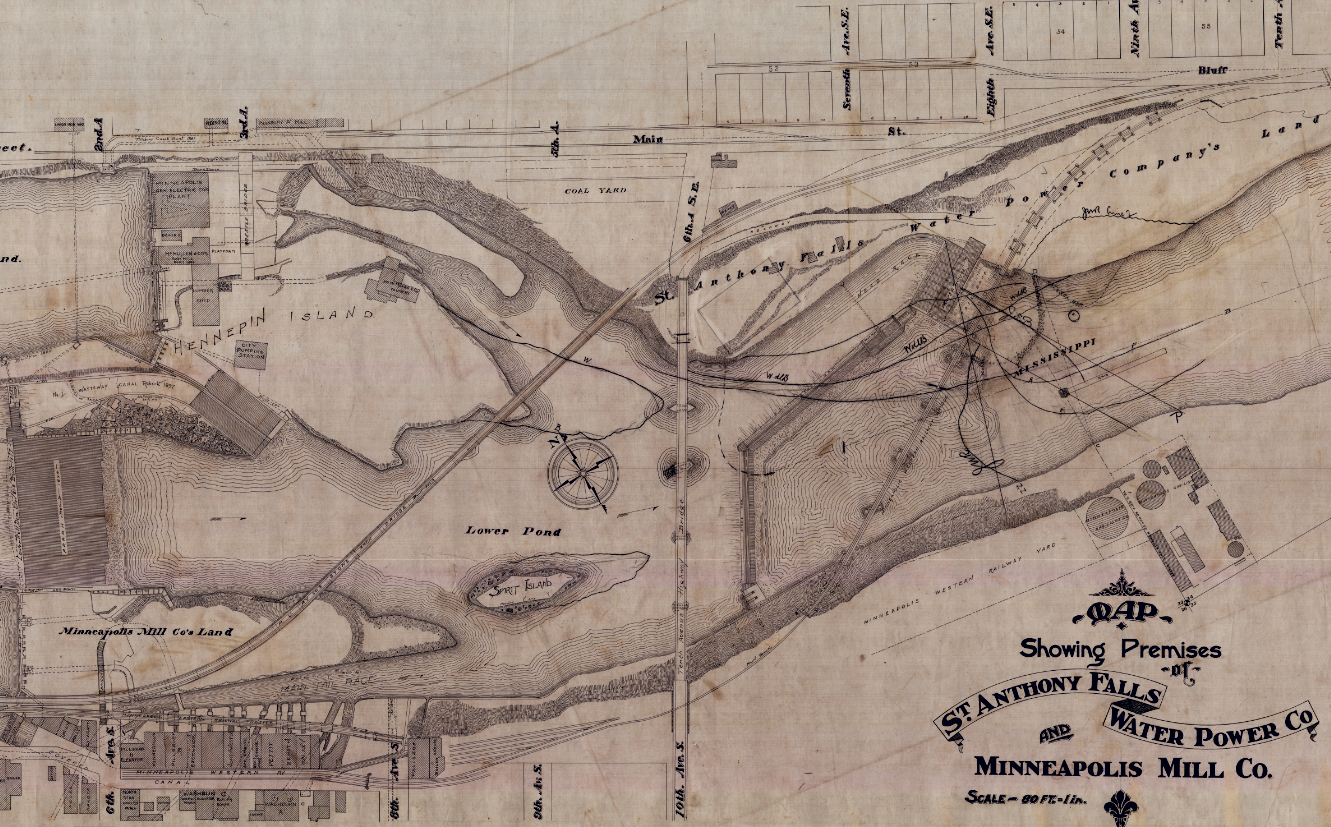

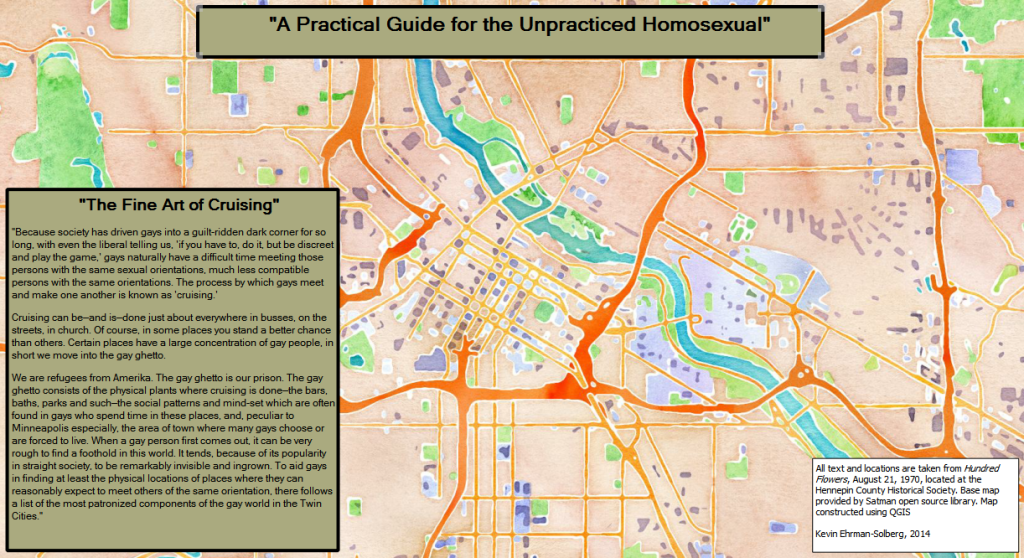

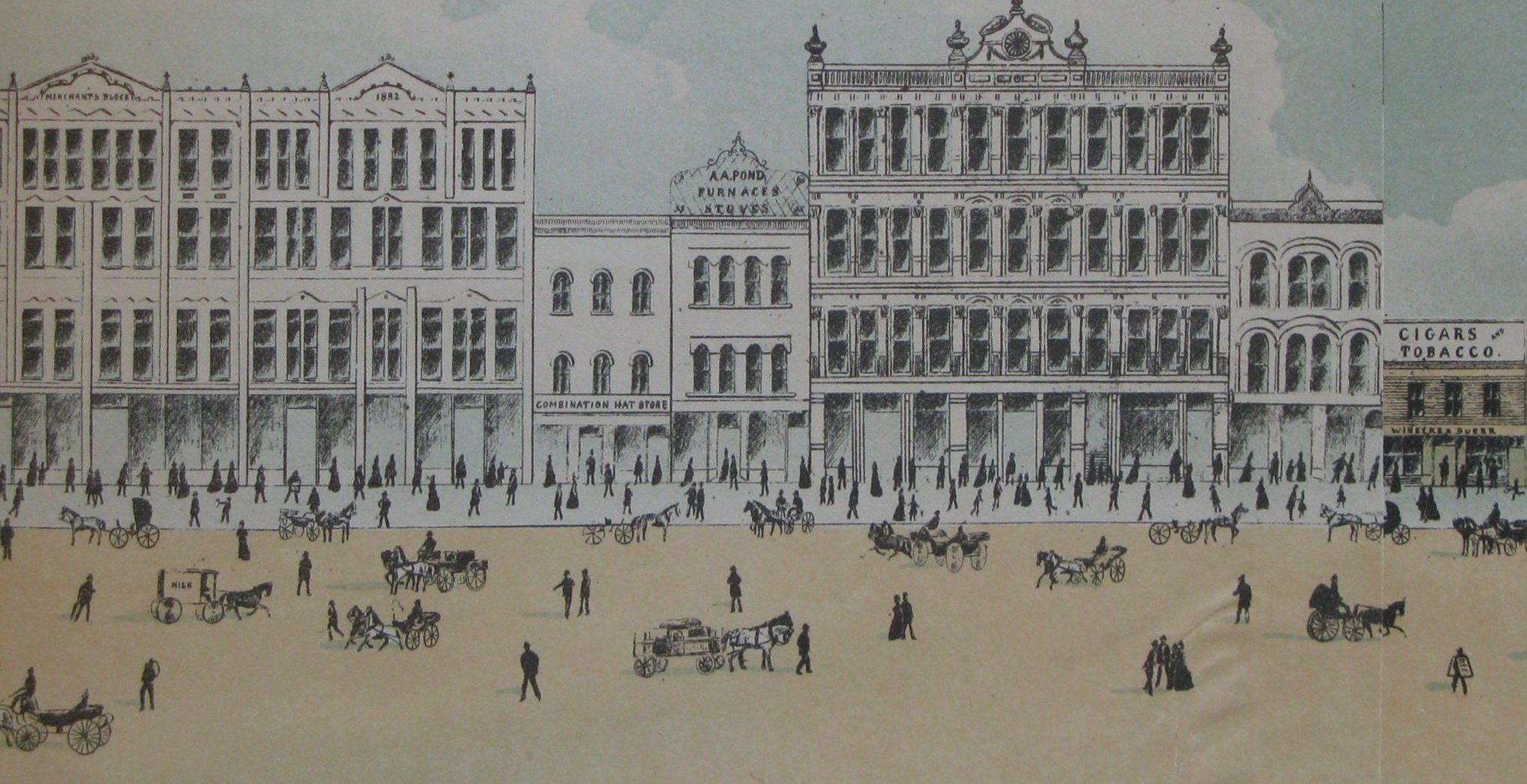

This project began this summer when the Historyapolis team found this amazing volume in the Hennepin County Historical Society.

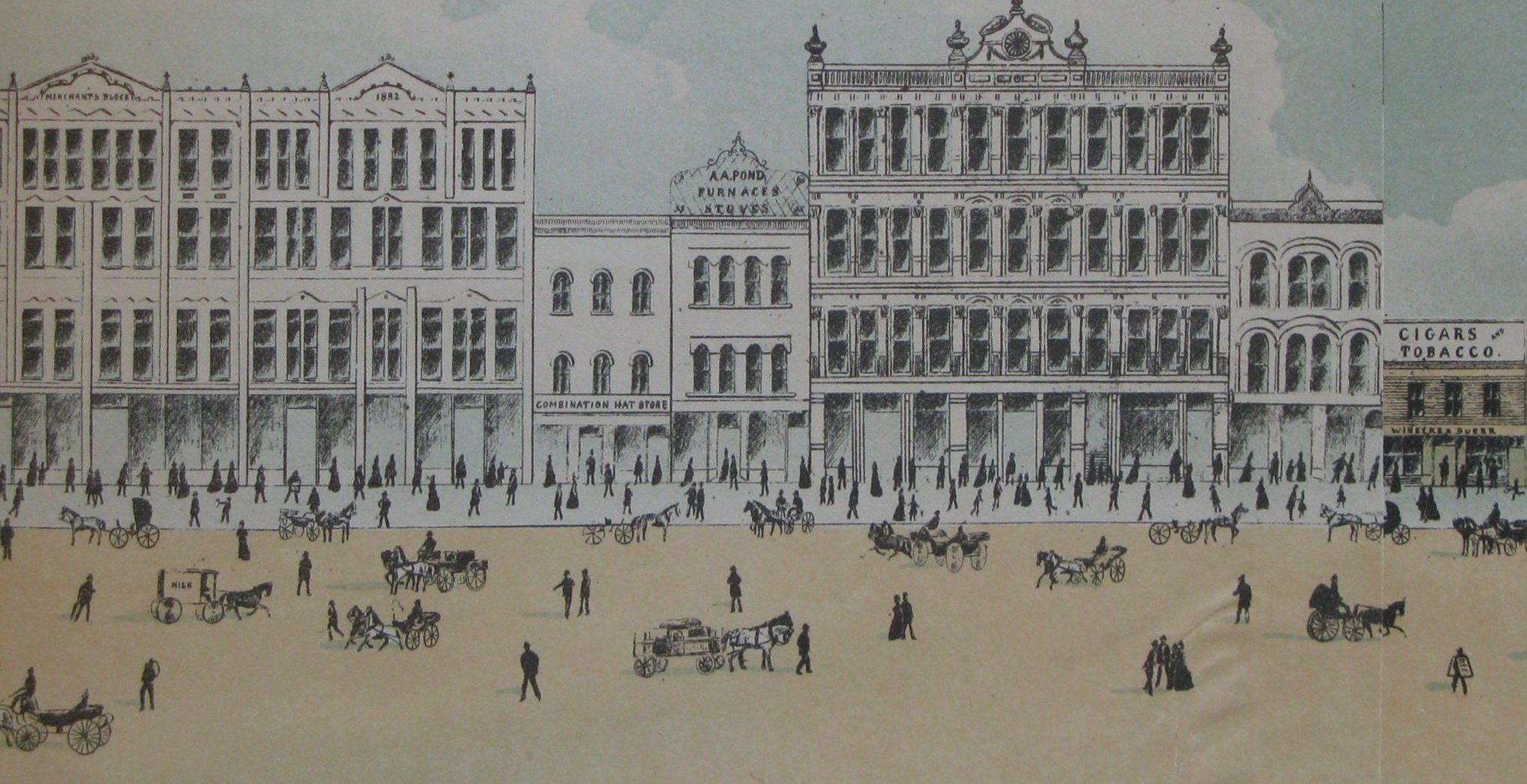

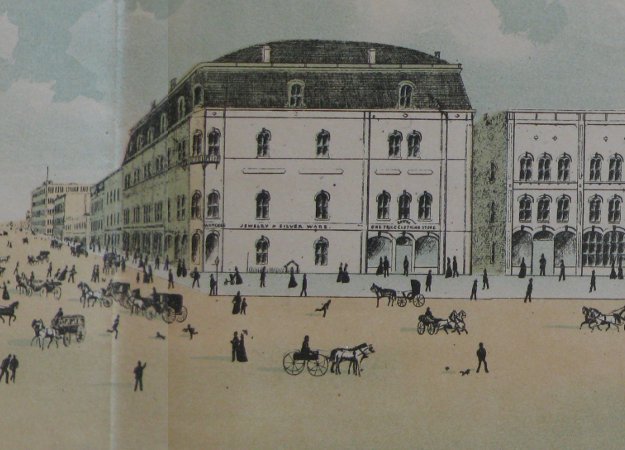

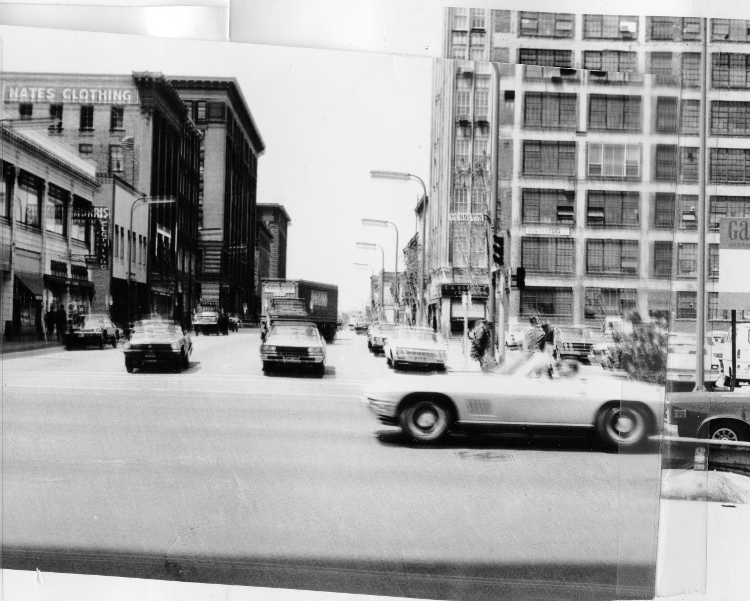

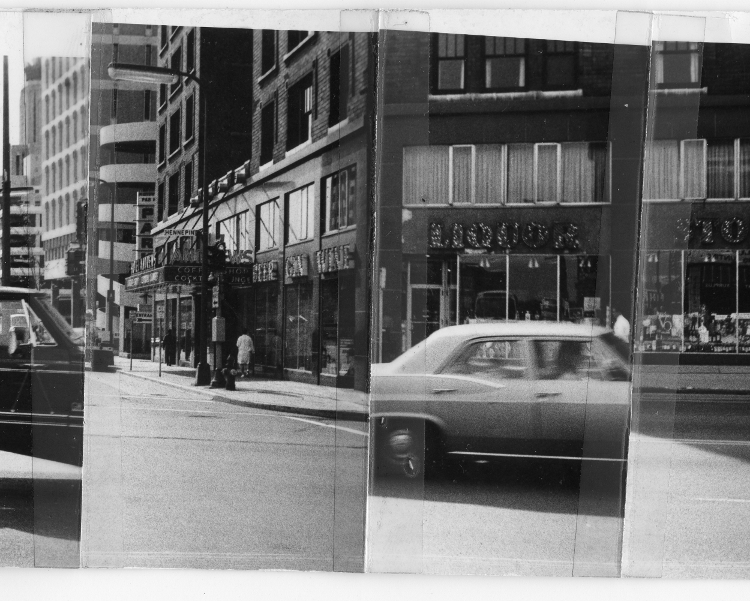

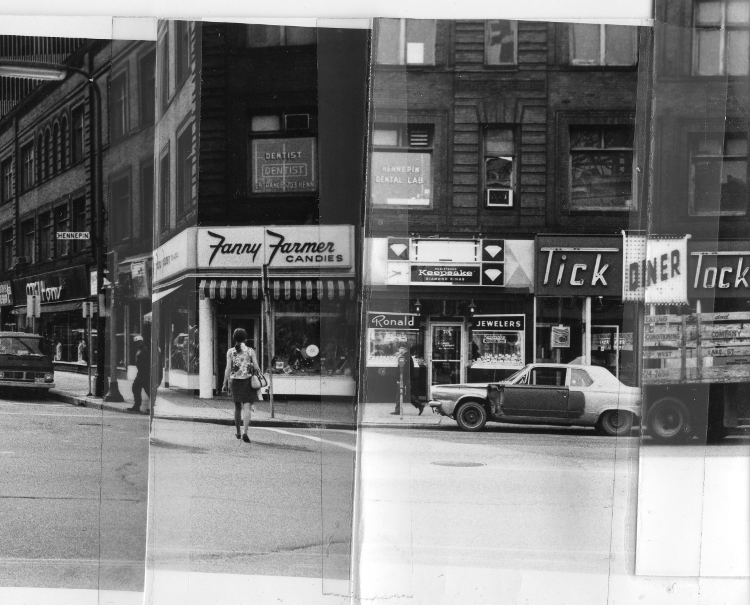

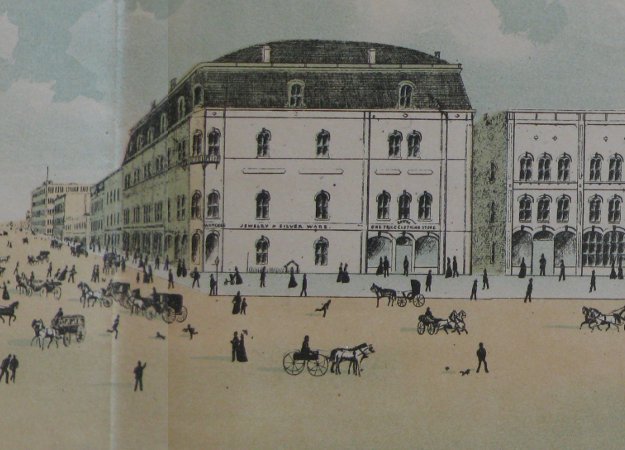

The Business Heart of Minneapolis was a promotional book–commissioned by civic boosters in 1882–that used intricate visuals to advertise the city’s prosperity in an effort to lure new investors. The book folded out accordion-style to reveal a hand-drawn panorama that showed Washington Avenue from Eighth Street South to Fourth Street North. Laid on the floor of the Hennepin History Museum, this delicate drawing stretched ten feet long and presented a carefully constructed image of a clean and orderly metropolis. It had none of the gritty quality of the Hennepin Avenue panorama we found earlier this spring. But like the 1970s montage, the Business Heart of Minneapolis was a Google-style streetview, constructed long before the advent of digital media.

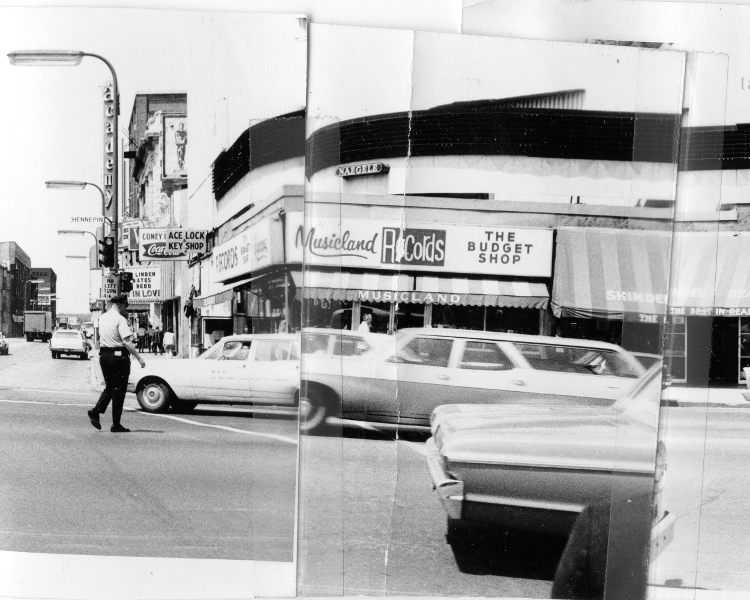

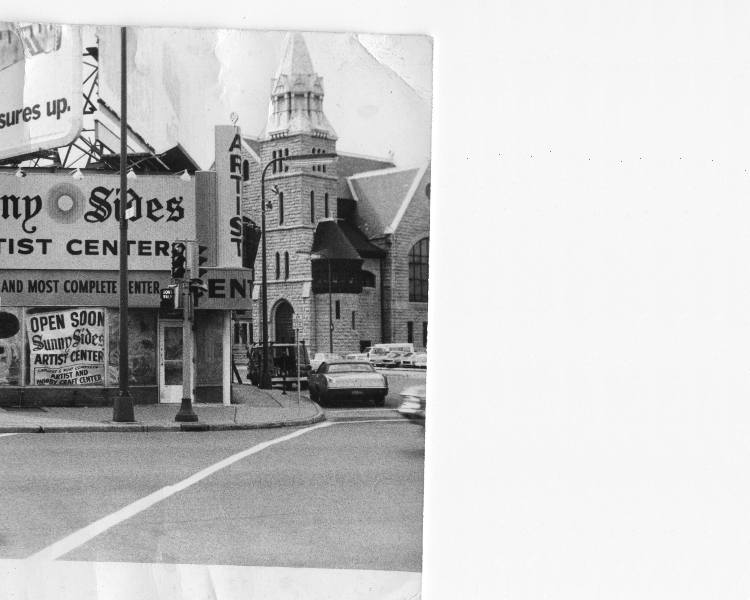

The Academy of Music building on the corner of Washington and Nicollet

The images were fascinating, transporting viewers back to the city during the Nineteenth Century. But they presented a challenge that prompted intense discussions. How could we present them to our readers? How could we use digital tools to share a drawing that stretches ten feet long?

What you see here is the product of these conversations. We decided to use twin image sliders. First, we digitized the original panorama and then cropped it into individual frames. Those images went into the top slider. We then took contemporary photos of Washington and put those underneath. The result is an interactive “now and then” exhibit that lets you compare—block by block—the Washington of the late 19th century with the street today.

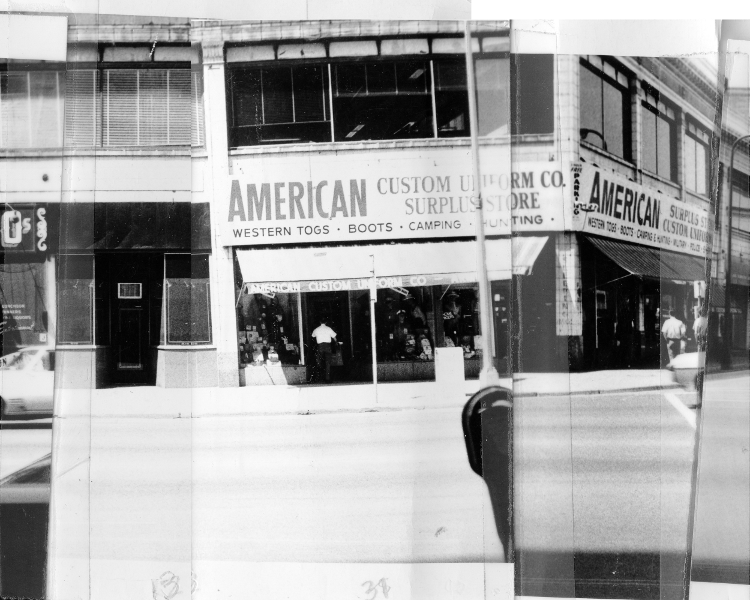

The Business Heart of Minneapolis illustrates the wide variety of business enterprises in operation along Washington Avenue in the last decades of the Nineteenth Century. The panorama featured the Kennedy Brothers gun store, which touted itself as the city’s source for the “best brands of gunpowder.” Shoppers could also peruse its wide selection of “roller and ice skates.” It showed the Anthony Kelly and Co. store, located on the corner of Second Avenue North. The Handbook of Minneapolis published by the Minneapolis Tribune asserted that the wholesale grocer “has in the minds of Northwestern tradesmen and the actual record of commercial life, been associated with all that was honorable in trade.”

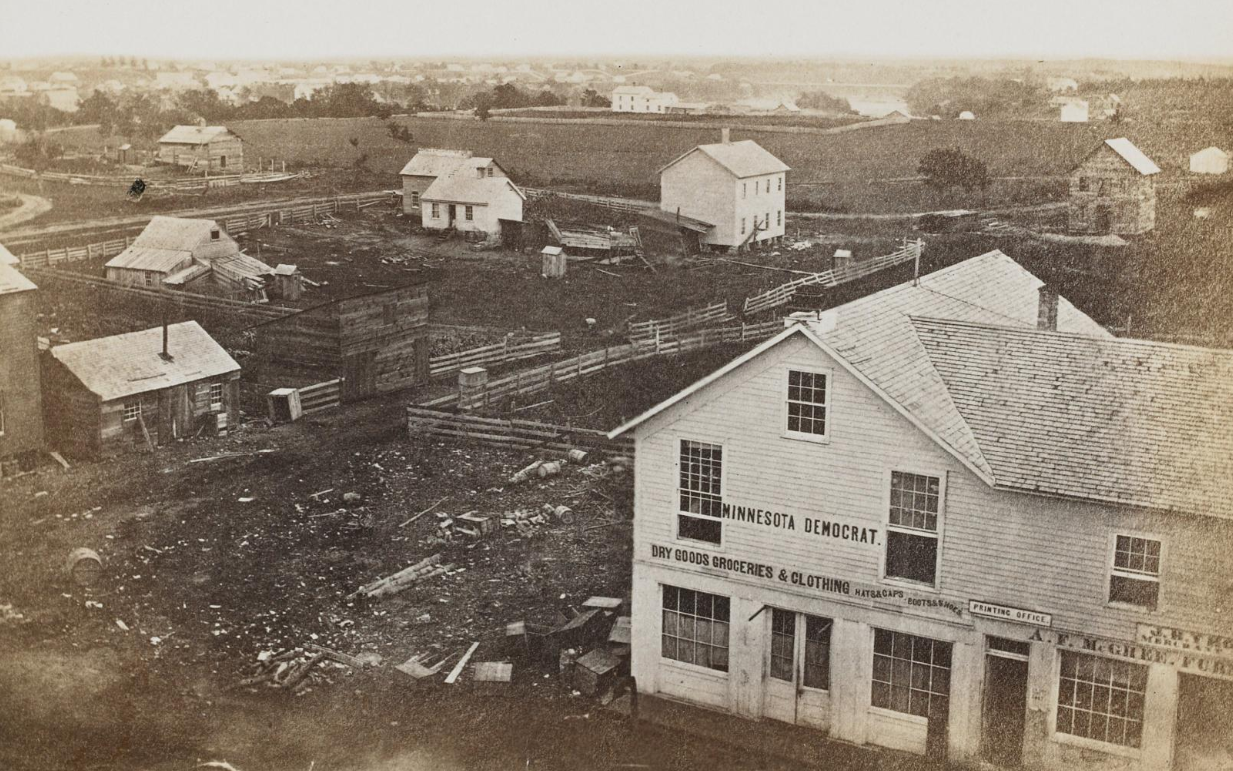

A quick look through contemporary photographs and other records shows that the hand-drawn panorama tells only part of the story. It presented a view that was both sanitized and idealized, part of a larger campaign by the business community to convince the world that Minneapolis “has become the wonder of the country,” in the words of the West Hotel Tourists’ Guide. “There is nothing of the mushroom about Minneapolis,” according to the Guide. “Its buildings are the most substantial, its paving of the best material…its business on a sound, conservative basis…its hotels models for larger and older cities.”

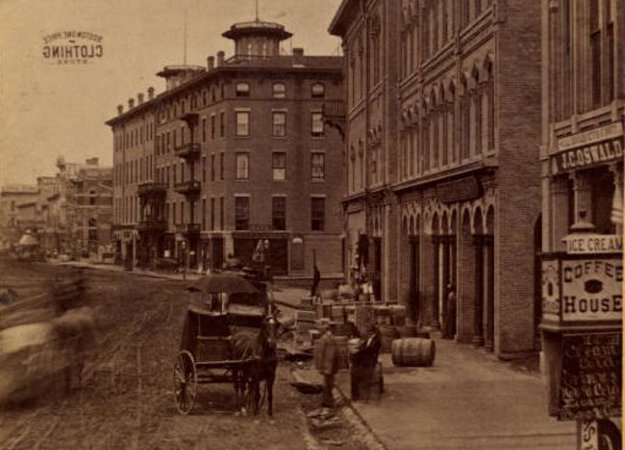

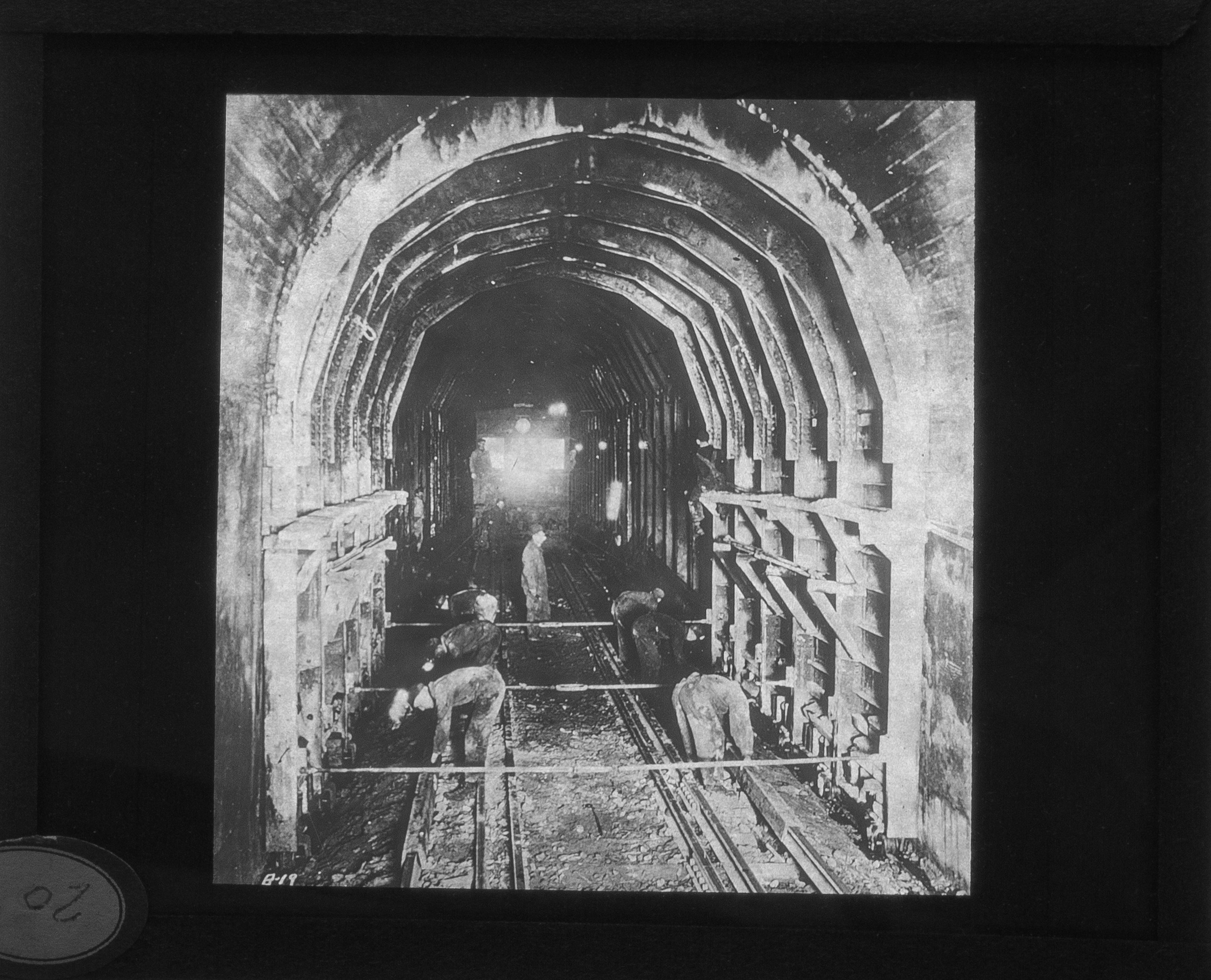

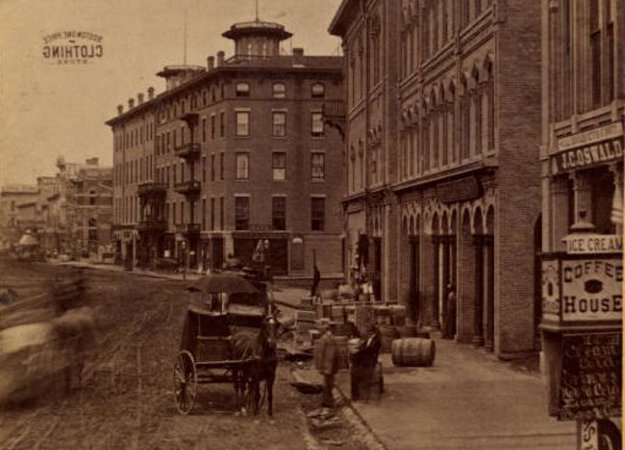

The image below, taken by William H. Jacoby, offers a more complex view of this important street.

Image courtesy of the Minneapolis Collection at the Hennepin County Libraries Special Collections.

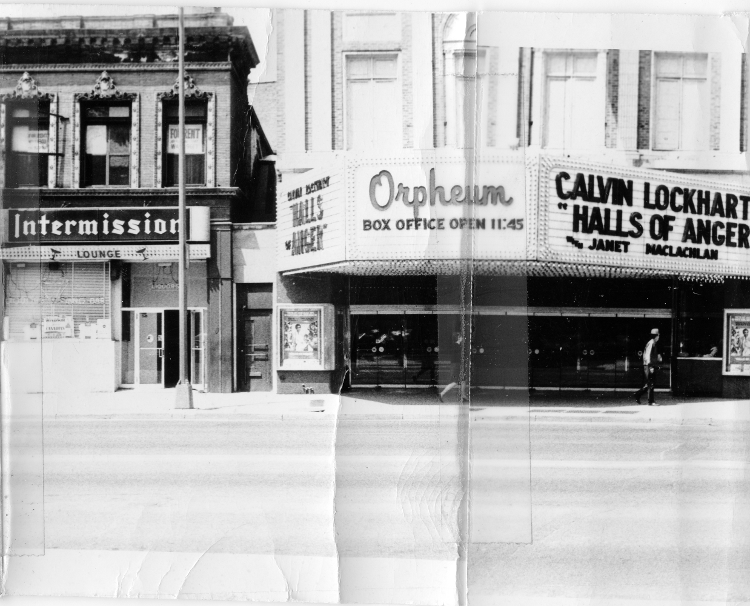

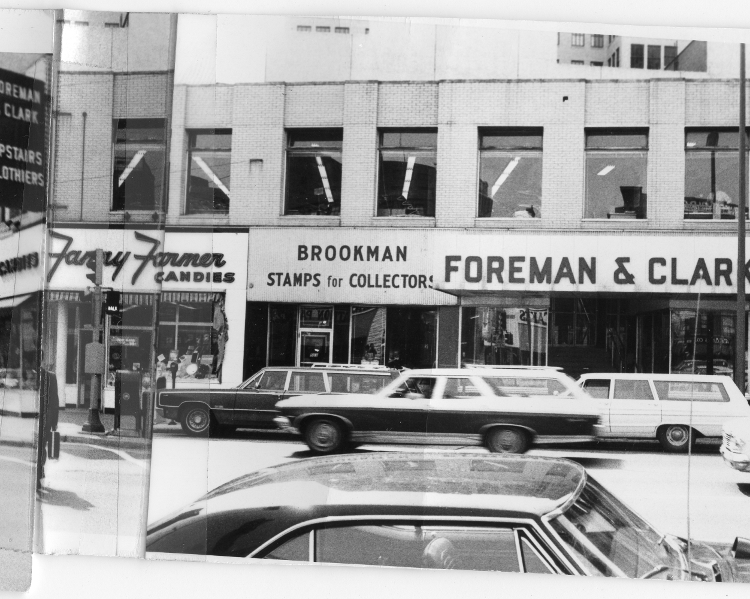

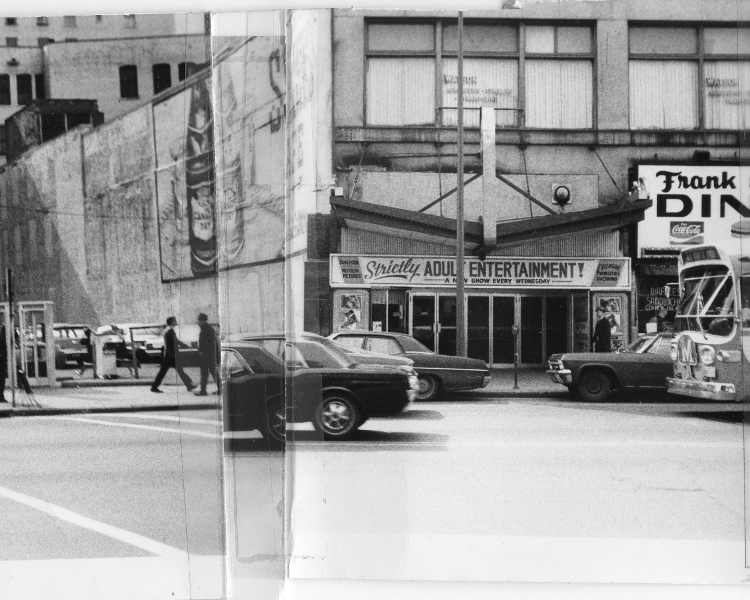

Unpaved streets, wooden plank sidewalks and dirt gutters make a powerful visual argument that Washington Avenue was not a picturesque commercial paradise. Liquor stores like J.C Oswald’s—shown at the far right of the image, next to the Academy of Music building—were far more common than “honorable” tradesmen like Anthony Kelly. The theaters lining the street—many intentionally omitted in the city panorama—were notorious. When the Louvre Theater opened in 1874, the Minneapolis Tribune described the entertainment as “buffoonery, with all the slang of a bagnio [brothel], and the most indecent gestures conceivable.”

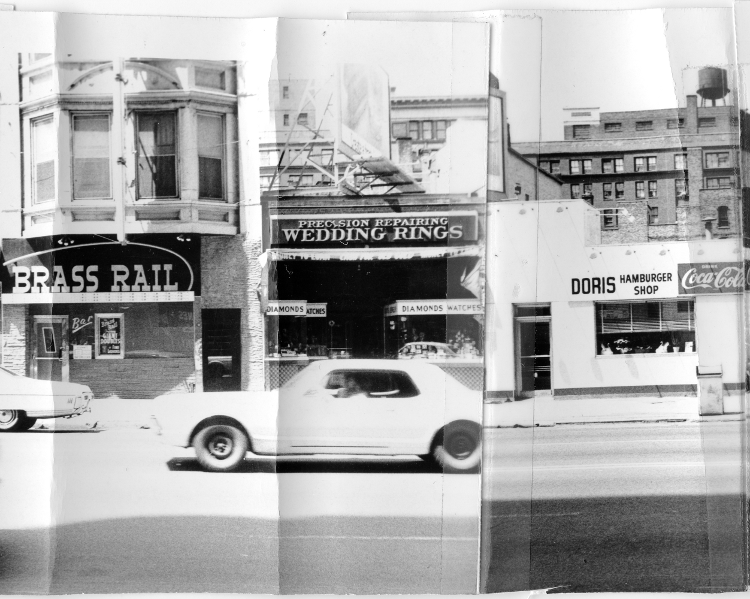

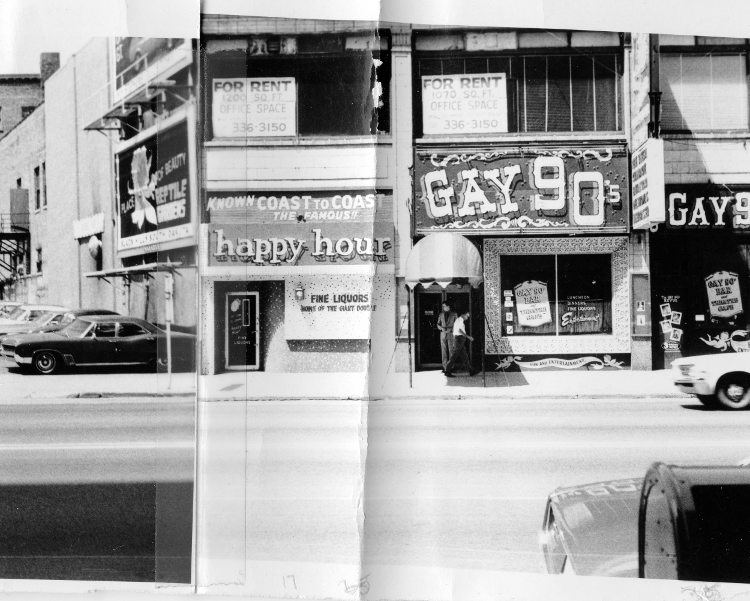

Only a few years after this lavish promotional book was produced, Washington Avenue had been usurped by Nicollet Avenue as the city’s main commercial artery. As retail shifted south, so did the hotels. The Nicollet House on the corner of Nicollet and Washington—which according to Minneapolis Tribune was “for many years the leading hotel of the city”—lost its primacy to the West Hotel on 5th and Hennepin. Washington Avenue, “with its over-supply of rumshops appeals to the vagrant class,” the Minneapolis Tribune declared in 1902. “In front of any of the saloons on this thoroughfare for four of five blocks the loafers congregate and vie with one another in spitting contests. As a rule, they spit toward the curb, but it is usually too far off and the sidewalk is stained a deep brown with tobacco juice, which doesn’t disappear very readily in dry weather.”

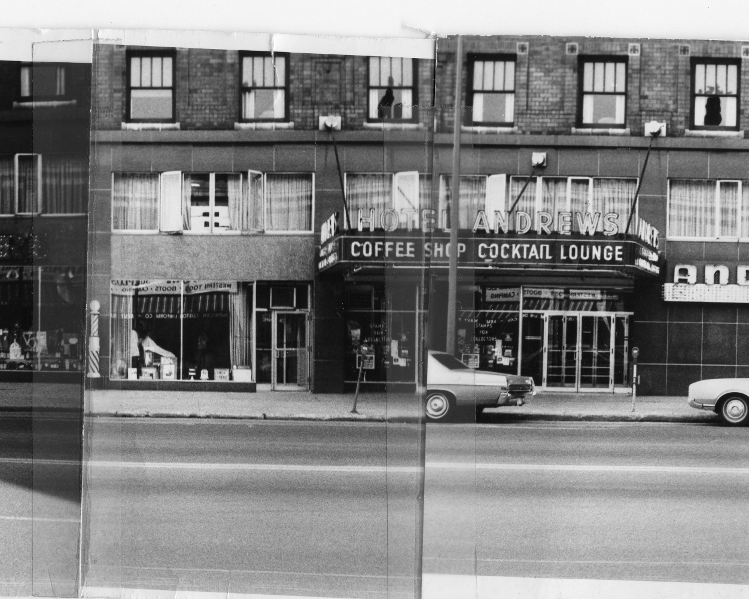

In the late nineteenth century, Washington Avenue was a study in contradictions, with upscale concert halls like the Academy of Music adjacent to bawdy show-houses. By World War I, these contrasts had faded as the street became the center of the region’s largest skid row. A magnet for anyone wanting to buy alcohol or sell sex, Washington Avenue was adjacent to a district of “Female Boarding Houses” (code for brothels), whose inhabitants plied their trade amidst the growing number of dive bars and saloons.

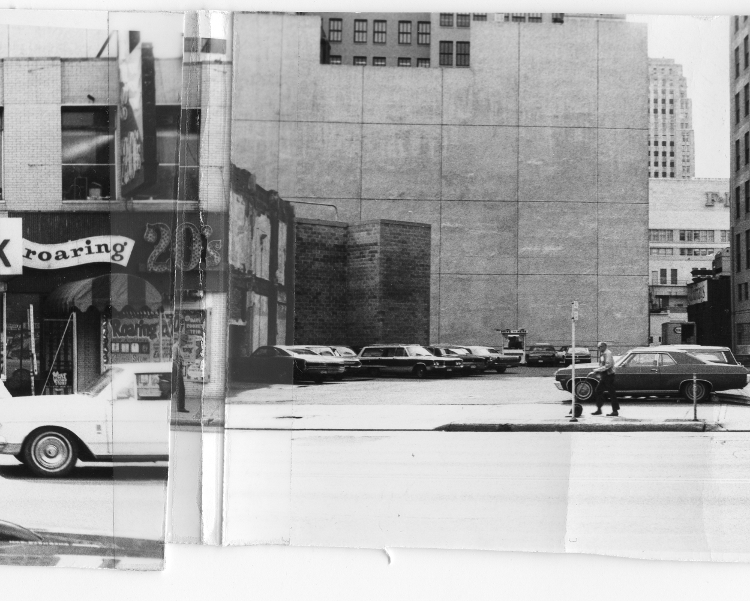

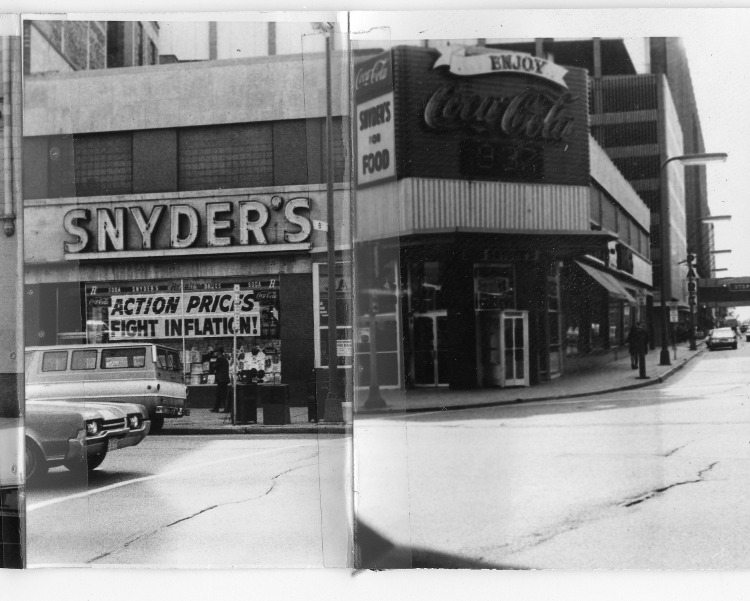

By the 1950s, Washington Avenue had become an unmitigated civic embarrassment. A rat’s nest of liquor stores, beer parlors and flop-houses—where seasonal railroad workers would hunker down through winter at the expense of 50 cents a day—the street bore little resemblance to its glory days as a booming business district. Johnny Rex, the so-called “King of Skid Row,” recounted an episode where a group of girls wrote to him to inquire if they could rent eight of his rooms, because they were attending a basketball tournament in the city. “If you did,” he replied, “you would never be the same. This is Skid Row.”

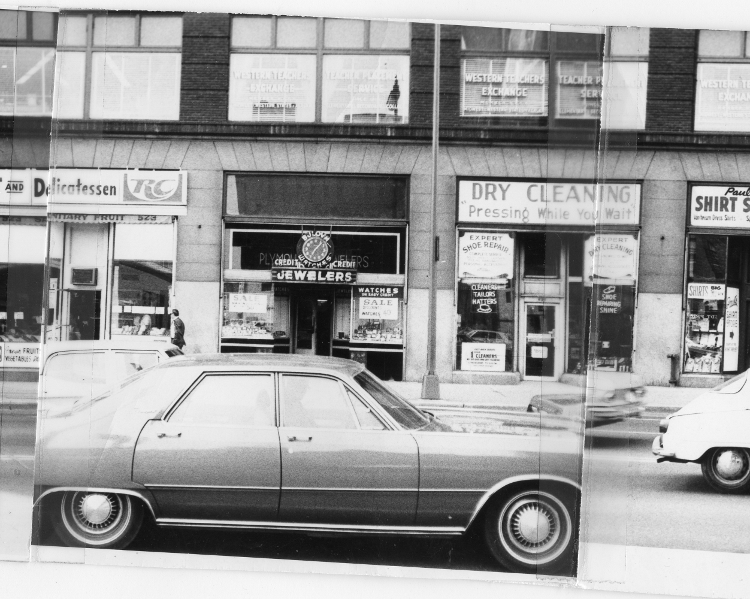

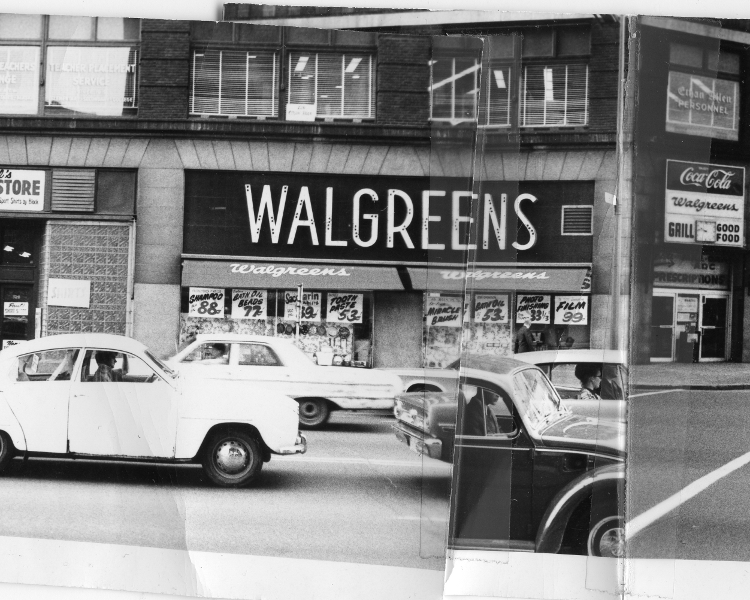

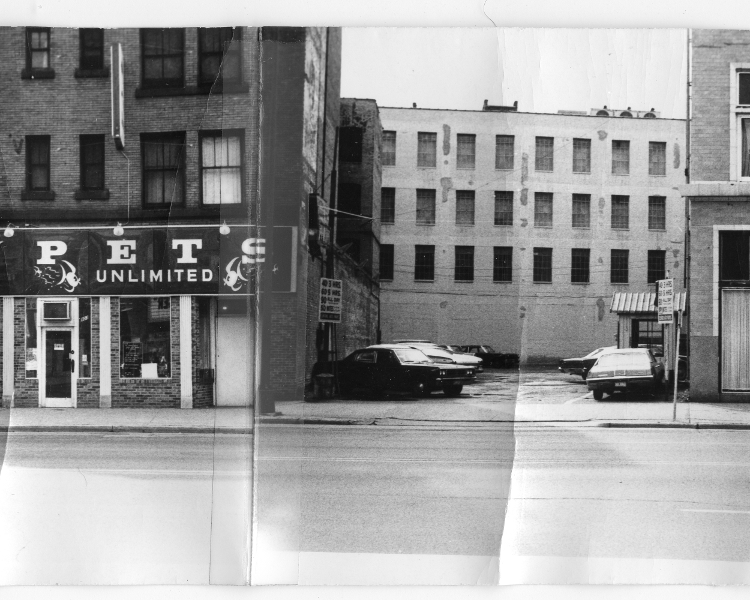

The corner of Washington and Marquette, taken in the late 1950’s. Johnny Rex’s bar, The Sourdough, is just off frame to the left. Image courtesy of the Hennepin County Historical Society.

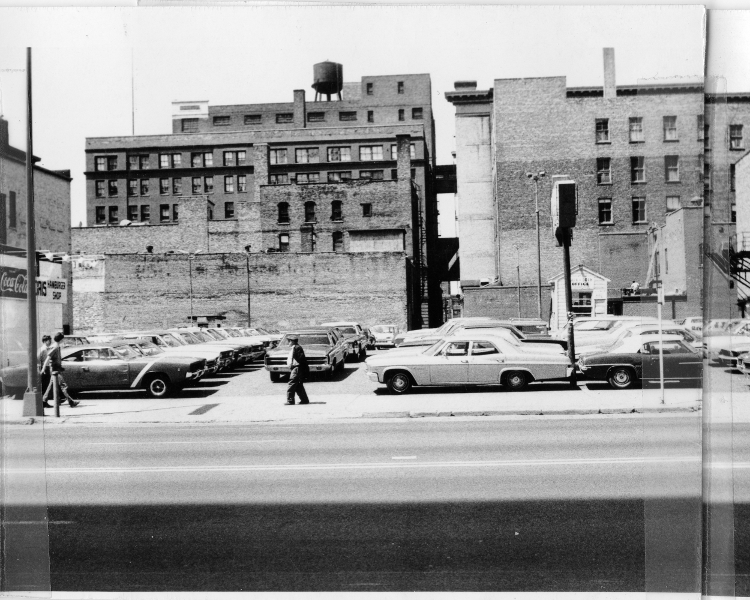

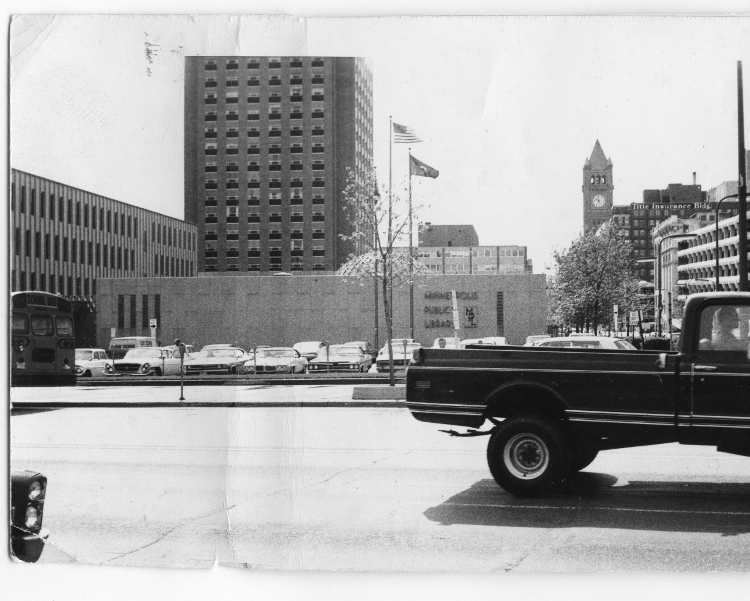

It was in this period that the city figured out how to get rid of the Gateway District, which included a large swath of Washington Avenue. Robert Jorvig–who was named the head of the Minneapolis Housing and Redevelopment Authority in 1956–explained that “the Lower Loop” was seen as “a tremendous void on the progress of the City of Minneapolis.” The Gateway “was where all the drunks and alcoholics were,” he asserted. “People got shot down there. You talk about people not going downtown now. In those days, people weren’t worried about crime in the streets and those kinds of things, but if you talked about wandering around on Washington Avenue, people were scared to death.” Jorvig was widely credited with managing the federally-funded effort to redevelop the Gateway between 1958 and 1965, when over 200 buildings, including most of the structures lining Washington, were destroyed.

The street today would be completely unfamiliar to the artist who rendered the drawings of 1882. The building that housed the wholesale grocer of Anthony Kelly and Co. is one of the only survivors of this wholesale demolition. The structure is still there, but is now occupied by Sex World. While jarring, the transition from grocery store to pornography shop does convey the turbulent history of Washington Avenue like nothing else still standing. Condos, coffee shops, corporate offices and parking lots now dominate the rest of the stretch. Of the grand old hotels and seedy dive bars, nothing remains.

Information from: The West Hotel Tourist’s Guide to Minneapolis and its Suburbs, C.W. Johnson, 1886; Tribune Handbook of Minneapolis, The Tribune Company, 1884; “Arts and Culture on the Riverfront,” Hess Rosie and Company, 2006; “Famous Visitors: When Washington Avenue was the Great White-Way,” Beatrice Morosco, 1972; Down on Skidrow, John Bacich and John Lightfoot; Sanborn maps of Minneapolis, 1912, sections 232 and 245; “Pandemonium,” Minneapolis Tribune, November 11, 1874; “They Loaf and Spit,” Minneapolis Journal, April 25, 1902; “The Ma Who Tore Down the Met,” interview with Robert Jorvig by Sallie Stephenson in 1982, Oral History Collection, Hennepin County Library Special Collections.