Today’s blogger is Kevin Ehrman-Solberg, a senior history major at Augsburg and an intern with the Historyapolis Project.

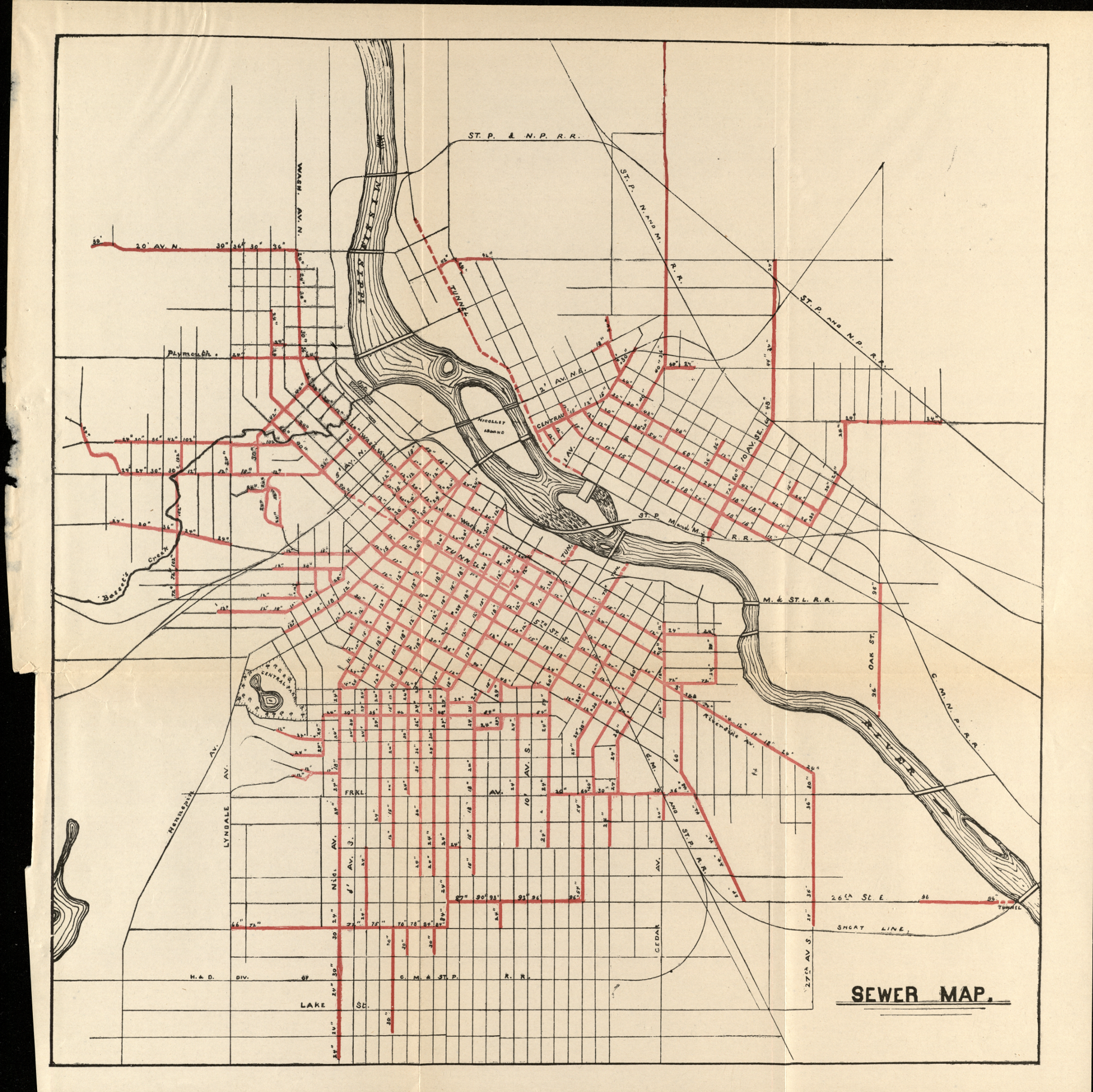

It’s map Monday. This 1889 maps shows the sewer system of Minneapolis. Today Minneapolitans take safe drinking water and flushing toilets for granted. During the Gilded Age, however, city-dwellers were not so fortunate. Like cities around the world, Minneapolis was grappling with the consequences of unprecedented urbanization. And one of the most pressing problems of this new human density was the question of waste. Cities had to figure out what to do with their often overwhelming supply of excrement.

One of the fastest growing cities in the county, Minneapolis only had 2.57 miles of sewers at the beginning of the 1880s. As a result, human waste literally filled the streets.

This was unpleasant. But it was also dangerous. In 1881, 1893 and again in 1897, the city endured epidemics of typhoid, a water-borne illness that spread when sewage and drinking water intermingled. According to the Annual Report of the Board of Health, 1897 alone saw 1,534 reported cases and 148 deaths.

The city responded to these public health crises with a sewer-building campaign. By 1890, the city had 63.5 miles of sewers, which this map shows stretching to Lyndale Avenue and Lake Street in the south and to Broadway street on the city’s north side. But this growing system still had some fundamental flaws, at least from perspective of public health. In 1889 Minneapolis Chief Engineer, Andrew Rinker, recommended dumping the sewer lines into Basset’s Creek as this would deposit “the sewage into the[Mississippi] river above the falls.” Unfortunately, the intake point for the city’s water supply was right next to the sewage outfall and lay “in the midst of that part of the stream polluted by a large share of the city’s sewage.”

In 1897, the city partially solved the water problem by relocating the water intake to the North Side pumping station. This new location was “situated above and beyond the great avenues of pollution.” However, as this map shows, the city’s sewer and water systems were still incomplete. By the turn of the century, many residents still relied on “privies” (private sewers) and surface wells.

This reliance could have dire health consequences. The Minneapolis Department of Health report for 1900 stated, in regard to recurring typhoid outbreaks, that “well water, infected by drainage from privy vaults or cess-pools, is the medium by which the malady is conveyed.” Indeed, the same report states that “by far, the majority of the contagious diseases and deaths occur in those districts which are supplied with well water.” The use of wells were especially common in the city’s poorer districts, such as Bohemian Flats.

Not only was the water delivery system incomplete, the North Side pumping station delivered untreated water from the Mississippi to Minneapolis residents well in to the 20th century. It was not until 1911 that the city began treating all municipal water with hypochlorite. The number of reported typhoid cases plummeted from 1,252 in 1910 to 290.

In the 1920s, the city still co-mingled its storm and sanitary sewer systems. As a result, raw waste was flushed into the Mississippi River. The city’s first wastewater treatment plant began operating in 1938. And it was during the decade of the Works Progress Administration that the city could finally get its sewer and water infrastructure aligned with its population. Today, the old sewage outfalls that line the Mississippi have been converted to storm drains.

Quotes and material for this post are drawn from the Proceedings of the City Council and the Annual Reports of the City of Minneapolis, 1889-1912. The map is taken from the 1889 Annual Reports. Thanks to Ted Hathaway at Hennepin County Special Collections for digitizing these maps for Historyapolis.