Author: Kirsten Delegard

A guide to traveling “without embarassment”

More than a decade before Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his legendary “I Have a Dream” speech, an African-American publisher named Victor H. Green articulated a modest vision for racial justice. “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States” he wrote, in the 1949 introduction to his Negro Motorist Green Book, which was a comprehensive listing of establishments friendly to African Americans. Updated annually between 1936 and 1964, when the Civil Rights Act banned racial discrimination in public accommodation, this slim volume was an essential resource for any person of color who wanted to travel “without embarrassment,” in the words of Green.

Green found opportunity in discrimination, providing an annual update of businesses in each state that were known to welcome African American patrons. But he bemoaned the necessity of this service. “It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please,” he concluded.

Hotels and restaurants in Minneapolis were prohibited from discriminating against African Americans. But laws did little to alter practices. “There were great restrictions placed on blacks in eating establishments, in hotel establishments,” labor organizer and business owner Anthony B. Cassius remembered in an oral history done in 1982. “Up until the late forties a Negro couldn’t stay in a downtown Minneapolis hotel. [There] was a gentlemen’s agreement.”

The 1949 Green Book corroborates Cassius’ memory. It advises African-American travelers to Minnesota to seek lodging in two places. First, the Serville Hotel, located at 246 4th Avenue in downtown Minneapolis, around the corner from the Milwaukee Road depot. On the edge of the Gateway District, the Serville appears to be an establishment with few pretensions and even fewer amenities. Photos from 1942 reveal it to be the kind of place that would welcome anyone–no questions asked–who provided cash upfront for his or her bill.

A more appealing option was the Phyllis Wheatley House at 809 N. Aldrich Avenue. Though it was not a hotel, this north Minneapolis settlement house provided a safe haven for traveling African Americans from the time it opened its doors in 1924. The settlement house moved into a new building in 1929 that included 18 bedrooms for travelers. In the years that followed it played host to the African American cultural and intellectual elite. Guests included labor organizer Philip Randolph, writer and historian W.E.B. Dubois, singer Marian Anderson, author Langston Hughes, folk singer and activist Paul Robeson and jazz artist Ethel Waters.

This 1936 photo of the Phyllis Wheatley Settlement House is from the Minneapolis collection at the Hennepin County Central Library.

Women’s Hockey in the Jazz Age

On January 10, 1926, these skaters on Lake of the Isles posed, smiling, with hockey sticks. Two of the players were women. This photo–along with many others from the decade–show that young women across the state were picking up sticks and enjoying recreational hockey match-ups. They were never allowed to shed their skirts for hockey pads or warm trousers. Yet the University of Minnesota recognized women’s interest in hockey during the Jazz Age, starting a club hockey team for women students.

World War II interrupted most recreational activities, including hockey. Demobilization brought what Betty Friedan later dubbed the “Feminine Mystique,” an increasingly rigid set of gender roles that emphasized domesticity and femininity for women. As the nation worked to move beyond the crises of war and economic collapse, women were expected to devote themselves to ever-more ambitious homemaking and were forced to give up the autonomy and financial independence they had gained by working in war industries. They were also expected to eschew competitive sports–especially those like ice hockey, which involved physical confrontation. Girls may have skated with their brothers and hit pucks around the city lakes. But their opportunity to compete on ice disappeared, unless they were willing to don figure skates and spangly costumes.

In 1972, Title IX was passed, requiring schools to provide equal athletic opportunities for girls. But it took more than a new law to create equal athletic opportunities for girls and women. Minnesota lagged in this regard, especially with hockey. No college hockey team existed for women in Minnesota until 1995, when Augsburg College put female Auggies on the ice. The University of Minnesota started its women’s hockey team in 1997.

Photo is from the newspaper morgue at the Minneapolis Collection, Hennepin County Central Library. Thanks to Rita Yeada for unearthing this image. And thanks as well to Annika Shiffer-Delegard, who helped me do the research necessary for this post.

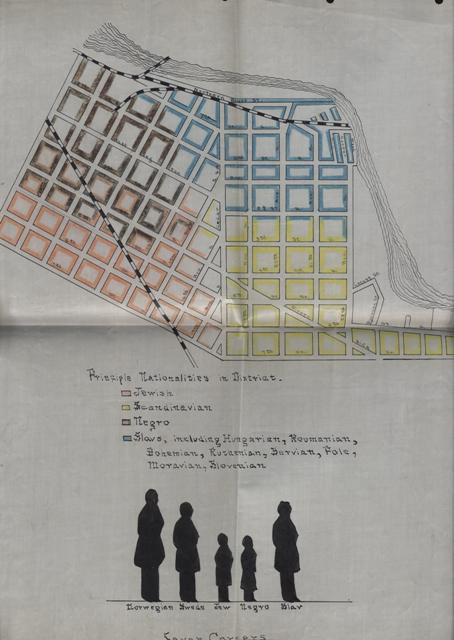

When Cedar-Riverside was “Snusgatan”

Minneapolitans love to reminisce about the counterculture years of the West Bank/Cedar Riverside neighborhood. But for most of the neighborhood’s history, small immigrant businesses like the Otanga grocery store–which was destroyed in yesterday’s fire–have dominated the commercial landscape. Here we have a photo from the 1890s that shows Charles Samuelson standing in front of his store in Seven Corners. The sign at the front reads: “Har Talas Svenska” (Swedish spoken here) and “Alla Slags Skadinaviska Tidningar Till Salu Har” (All types of Scandinavian Newspapers for sale here). Samuelson was obviously catering to the residents of the immigrant-dominated neighborhood. In addition to newspapers, he stocked tobacco, candy, fruit and sodas in his store at the corner of Cedar and Washington Avenues.

“Snusgatan” or Cedar Riverside was the commercial center of the Scandinavian immigrant community at the turn of the twentieth century. New arrivals settled in boarding houses in the neighborhood, patronizing stores like Samuelson’s, where they were not expected to have a mastery of English. The neighborhood stood in close proximity to the city’s industrial zone, making it easy for new immigrants to walk to jobs in the mills. And after work, new arrivals could socialize in the neighborhood’s myriad dance halls, saloons, theaters and meeting halls. “Att ga pa Cedar” (to walk on Cedar) became shorthand for “to get drunk.” As immigrants started families and became more established, they tried to move out of the neighborhood. Scandinavians usually aspired to move into South Minneapolis, where they built large neighborhoods of working-class homes.

I’m guessing that both Charles Samuelson and the owners of the popular Otanga Grocery would have been equally perplexed by the media antics of the Electric Fetus music store, which staged a “naked sale” in 1972.

Photo is from the collections of the Minnesota Historical Society.

R.I.P, 514 Cedar Avenue

Tragic news from the Cedar Riverside neighborhood, where 514 Cedar Avenue exploded this morning. At least 13 people were injured in the blaze; as of this writing, three people have not been found in the icy ruins. The building’s first floor contained a small grocery that catered to the tastes of the immigrant neighborhood. Upstairs were inexpensive apartments that provided basic housing for new African immigrants.

When Peter Nordberg constructed this building in 1886, he designed it to house two stores on the first floor and “twenty room flats” above. At this time, this section of Cedar Avenue was known as “Snusgatan” and was the commercial center for new Scandinavian immigrants. The traditional gateway for newcomers to the city, the neighborhood began to transform once immigration slowed to a trickle during the Great Depression.

In 1968, the struggling Cedar Riverside neighborhood provided the perfect location for a new commercial endeavor envisioned by two U of M students. Ron Korsh and Dan Foley started the Electric Fetus music store at 521 Cedar Avenue in 1968, hoping to sell the psychedelic rock music they heard coming out of San Francisco. Korsh quickly became bored with the store and sold his share to Keith Covart, who is crediting with making the business a long-lasting success.

These counterculture entrepreneurs kept their store in the news. In 1969, police confiscated a poster from the store that depicted a nude couple resembling President Richard Nixon and his wife. Notoriety (and low record prices) helped the store to grow, forcing it to seek larger quarters across the street. In October, 1969 it moved into 514 Cedar Avenue, the building destroyed in this morning’s blaze.

In 1970, Covart was arrested after the store displayed a United States flag with a peace symbol superimposed in the spot usually reserved for the 50 white stars. In 1972, the store held a “naked sale,” offering free records and pipes to nude patrons. After fifty people showed up to claim their free merchandise, the store lost its lease on Cedar Avenue.

With the influx of Somali immigrants, Cedar Riverside has once again become a first stop for new arrivals to the city. And the building at 512-516 Cedar had reverted to its original purpose. The tiny apartments and ethnic businesses destroyed this morning would have seemed very familiar to Peter Nordberg, the nineteenth century entrepreneur who recognized the economic potential of a new immigrant community.

Photo from the Minnesota Historical Society. And material for this post is taken from the excellent history of the Electric Fetus written by Penny A. Petersen and Charlene K. Roise in July, 2006.

Cream of Wheat: Race and the Birth of the Packaged Food Industry in Minneapolis

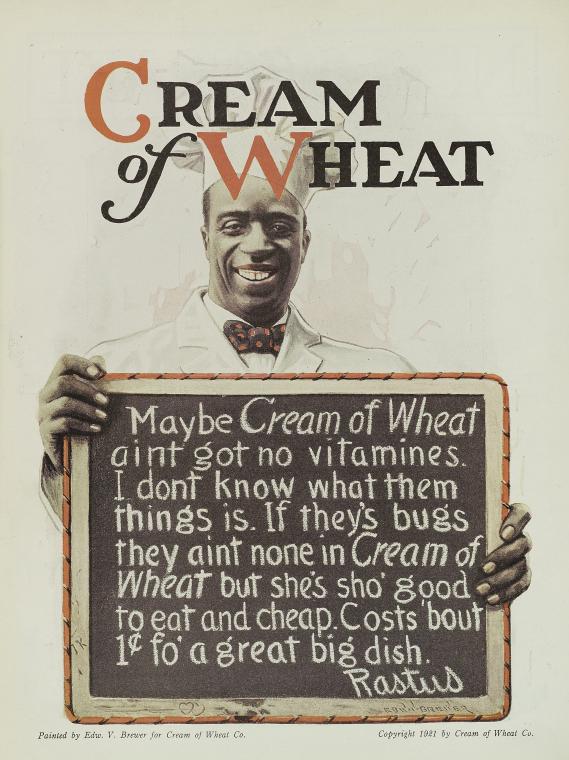

At a moment when Minneapolis had a very small African American community, the city became home to “Rastus,” an iconic caricature of a black man. “Rastus” was the symbol of the Cream of Wheat company, which relocated to Minneapolis in 1897 from North Dakota. Over the next 100 years, he was welcomed into households across the country.

Four years earlier– a group of North Dakota millers devised a way to turn wheat middlings–a byproduct of wheat milling–into a lavishly packaged “breakfast cereal” they called Cream of Wheat. Short on capital, miller Emery Mapes designed the packages for the “breakfast porridge” himself, emblazoning the cartons with an image of a jolly African-American chef he called “Rastus” after the cheerful simpletons depicted by Joel Chandler Harris in his Uncle Remus books. The image was offensive; like Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben, this figure solidified white stereotypes of happy black servants. But the product was an enormous success, despite the desperate economic conditions of the country in 1893.

The Cream of Wheat company moved to the Mill City to ensure advantageous shipping rates and a dependable supply of the middlings necessary for its cereal. It pioneered a strategy that would prove central to the city’s economy by the 1920s, as Buffalo superseded Minneapolis as the nation’s milling capital. Cream of Wheat used innovative advertising and branding to create value for consumers. Using four-color printing the company cultivated desire for what was an inexpensive commodity. The artfully-depicted scenes on the packages curried nostalgia for a simple and wholesome era of American life, when racial and ethnic hierarchies were unquestioned. The processed food industry was born.

The image of the former slave–“Rastus” –was central to the success of this product, which made company founder Emery Mapes millions of dollars. In this 1921 advertisement, Rastus was depicted as barely literate. His sign reads:

Maybe Cream of Wheat

Ain’t got no vitamins.

I don’t know what them

Things is. If they’s bugs

They ain’t none in Cream

Of Wheat but she’s sho’ good

To eat and cheap. Costs ‘bout

1 cent fo a great big dish.

The proceeds from this campaign built 2218 Lake of the Isles Parkway, a grand mansion for Emery Mapes on the city’s most elite lake. Despite ongoing protests, Rastus remains the personification of Cream of Wheat cereal today.

Advertisement is from the collections of the New York Public Library. It was published in Needlecraft Magazine from 1921 to 1923.

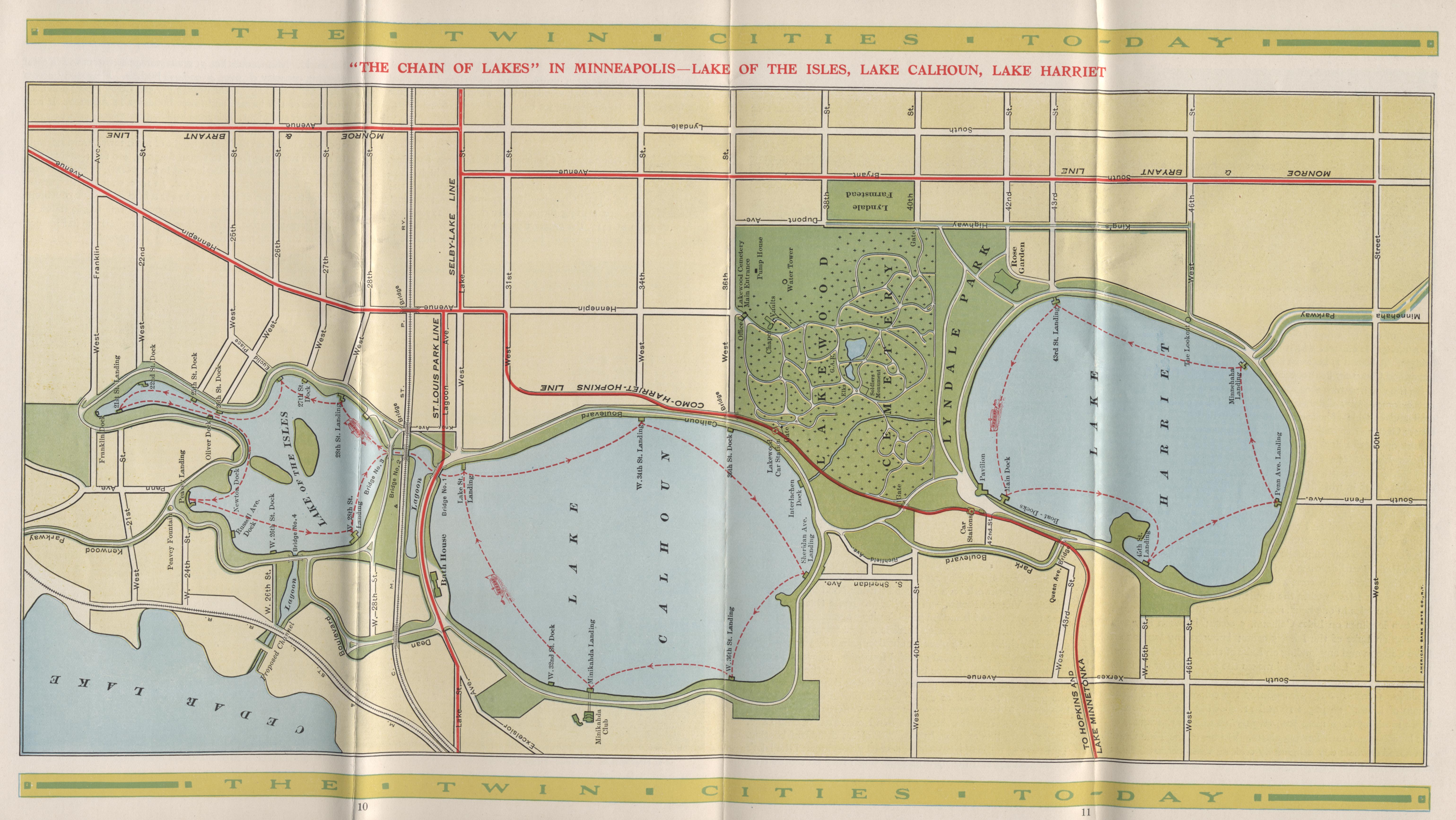

Tour the Chain of Lakes

It’s map Monday.

This 1913 map from the Twin Cities Transit company touts the attractions of Minneapolis of the city’s beloved chain of lakes. The red lines on the lakes trace the routes of the “launches” that circumnavigated Lake Harriet, Lake Calhoun and Lake of the Isles. “The ‘Maid of the Isles’ makes the 8 mile tour of Lake Calhoun and Lake of the Isles in one hour; round trip 20 cents,” the brochure, Twin Cities today explained. “Fare between any two landings on Lake Calhoun, 5 cents; between any landings on Lake of the Isles 5 cents; between any landing on Lake Calhoun and any landing on Lake of the Isles, or vice versa, 10 cents. The ‘Lake Harriet’ makes the 3.5 mile tour of Lake Harriet in 25 minutes; round trip 10 cents. Fare between any two landings, 5 cents…Visitors to the Twin Cities can spend a whole day delightfully cruising these charming lakes and enjoying their interesting shores.”

Pamphlet is from the Minneapolis collection, Hennepin County Central Library.

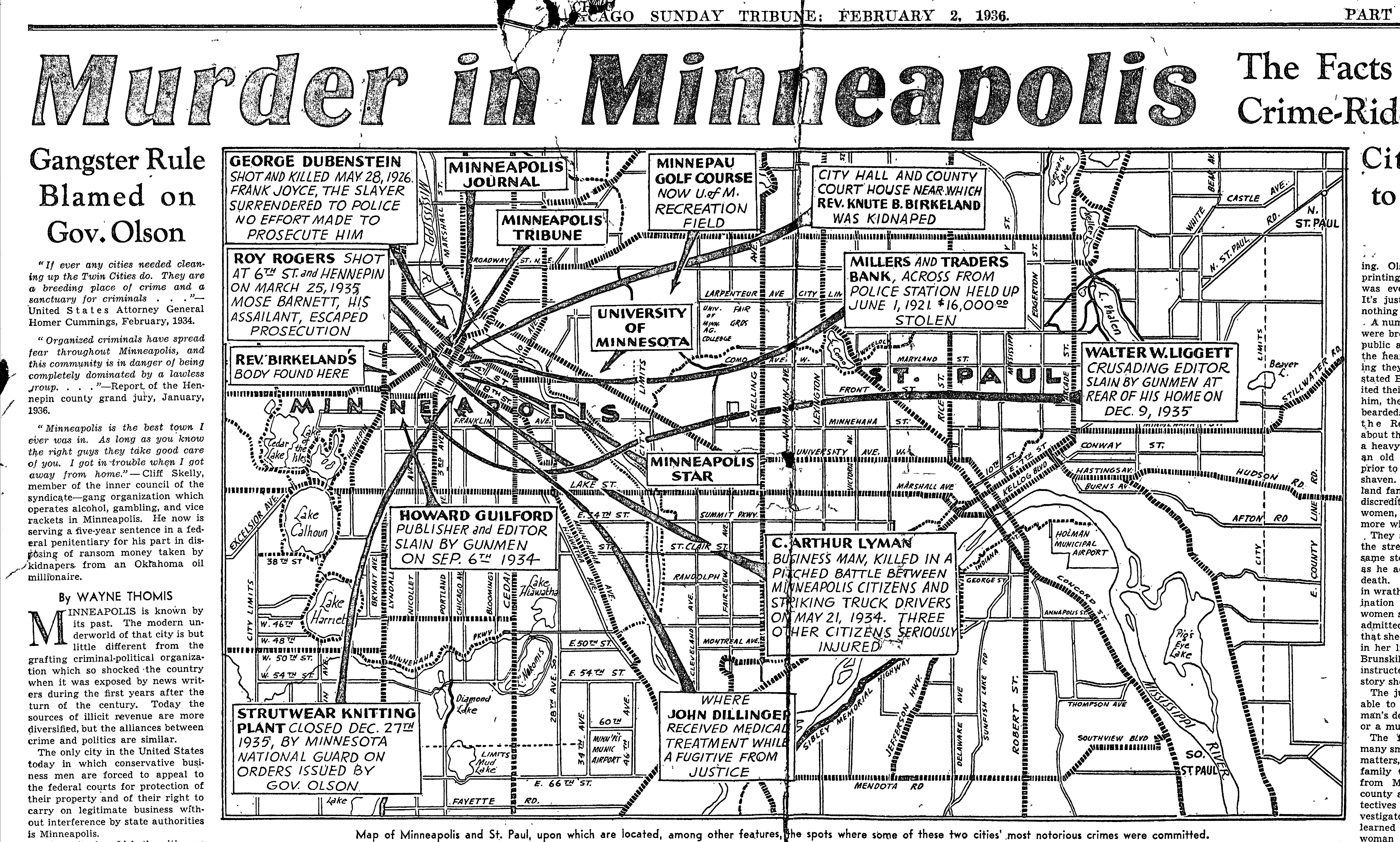

The Murder of Walter Liggett

Murder in Minneapolis, 1936

It’s map Monday.

Published by the Chicago Tribune in 1936, this “Murder in Minneapolis” map was designed to illuminate “the Facts about a Crime-Ridden City.” Compiled as the city hit bottom, the diagram reflects the town’s unsavory reputation in 1936. Between the Teamsters’ strike of 1934 and 1946–when Minneapolis earned the ignominious title of “anti-Semitism” capital of the United States–the city was regarded with fascinated horror by the rest of the country. One report after another declared that Minneapolis was beyond repair–its economy in tatters, its social relations poisonous, and its criminal element unchallenged. In the article accompanying this diagram, Tribune reporter Wayne Thomis wondered: “Why is it that the decent-law-loving men and women who live in that city and state do not take some bold direct action to eliminate gangsters, gang lawyers and hoodlum-befriending politicians?”

This “expose” of Minneapolis was compiled by the conservative Chicago Tribune, which laid responsibility for the city’s lawlessness at the feet of the state’s political radicals. The accompanying article was a screed against Minnesota’s Governor Floyd B. Olson, who grew up on the Northside of Minneapolis and went on to become District Attorney of Hennepin County before winning the governorship. In the early years of the Great Depression, Olson became nationally known for his fiery radicalism, declaring in 1934: “I am not a liberal. I am what I want to be — a radical.” He was seen as presidential material in 1936, a challenge from the left to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Conservatives (including Tribune publisher McCormick) hated him for his radical rhetoric, though he governed pragmatically until he died prematurely from stomach cancer, seven months after this article was published.

The map highlighted some of the deaths associated with the labor violence that had rocked the city since the global economic collapse. The article and accompanying graphic also detailed a series of murders that were blamed on local mobsters, including those of crusading journalists Walter Liggett and Howard Guilford, who sought to expose the connections between the state’s political and underworlds.

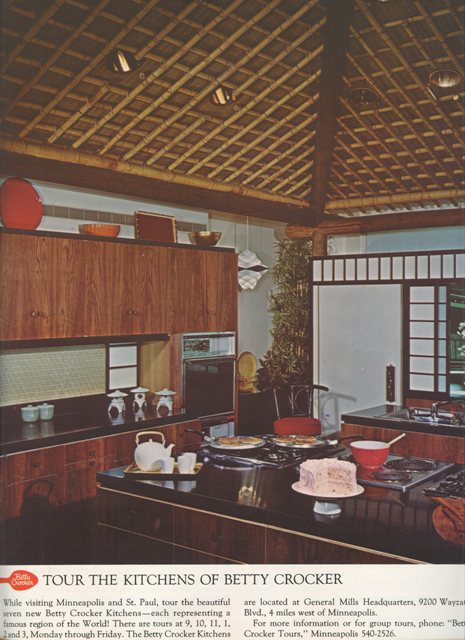

“Betty Crocker Tours”: Minneapolis 540-2526

This advertisement invites anyone visiting Minneapolis to tour the kitchens of Betty Crocker, who was one of the best known and most admired American women in the years after World War II. Crocker was not a real woman. She was the fictional household expert fabricated to personify General Mills, the food processing giant that had consolidated the Minneapolis milling industry during the 1920s.

The incorporation of General Mills was a significant turning point for the city, which was struggling to cope with the agricultural depression that had gripped the region since the end of World War I. The new company signaled a shifting economic base for the city, which was transformed from a milling capital to a center for new consumer industries by the end of World War II. The city’s grain mills stayed intact. But business leaders used the profits they had gleaned from milling wheat and timber to create a new generation of industries that were heavily dependent on sophisticated marketing techniques. General Mills sold pancake mix as well as plain flour; it devised labor-saving packaged foods that it had to convince traditional cooks to buy. This economic shift meant that business leaders became increasingly concerned with the national reputation of their city, as the image of the city and the products it products was inextricably connected. Starting in the late 1930s,the business community bought billboards, launched the Aquatennial and then supported the mayoral campaign of Hubert Humphrey, all in an effort to build a new reputation for a city known for labor violence, gangsters and anti-Semitism.

By the time this advertisement was published in 1968, Crocker’s kitchens had moved out of downtown Minneapolis to an expansive corporate campus in Golden Valley. A far cry from the old Grain exchange, which banned visitors from the grain trading floor, General Mills worked to lure customers to its headquarters, where they could sample new products. General Mills fashioned itself into a Disneyland-style tourist destination, building a series of test kitchens meant to evoke California, Hawaii, the Arizona Desert, Cape Cod, Chinatown, the culture of the Pennsylvania Dutch and colonial Williamsburg. Tours ran six times a day, Monday through Friday. To arrange a visit they had only to phone: “Betty Crocker Tours,” Minneapolis 540-2526.