Today’s blogger is Heidi Heller, a senior history major at Augsburg and an intern with the Historyapolis Project.

Tucked among Mayor Arthur Naftalin’s files in the Tower Archives at Minneapolis City Hall is a letter written in 1962. Addressed to members of the Commission on Human Relations–which was charged with addressing problems of racial discrimination and conflict in the city–it warned that Minneapolis would probably see an influx of “Reverse Freedom Riders” right before Christmas.

Fifty years later, no one remembers the “Reverse Freedom Riders,” a mean-spirited publicity stunt devised by segregationists associated with the White Citizens Council in New Orleans. This group recruited African Americans who were interested in leaving the South, giving them one-way bus tickets and a promise that “northern cities will certainly welcome you and help you get settled.” Participants were unaware that the communities at the end of their journey were unprepared for their arrival. Intended to embarrass white supporters of the African-American freedom movement, this effort was the brainchild of George Singelmann, who sought to “expose the hypocrisy” of Northern communities seen as widely supportive of civil rights. Minneapolis–along with Philadelphia, New York and Chicago –was one of the cities targeted.

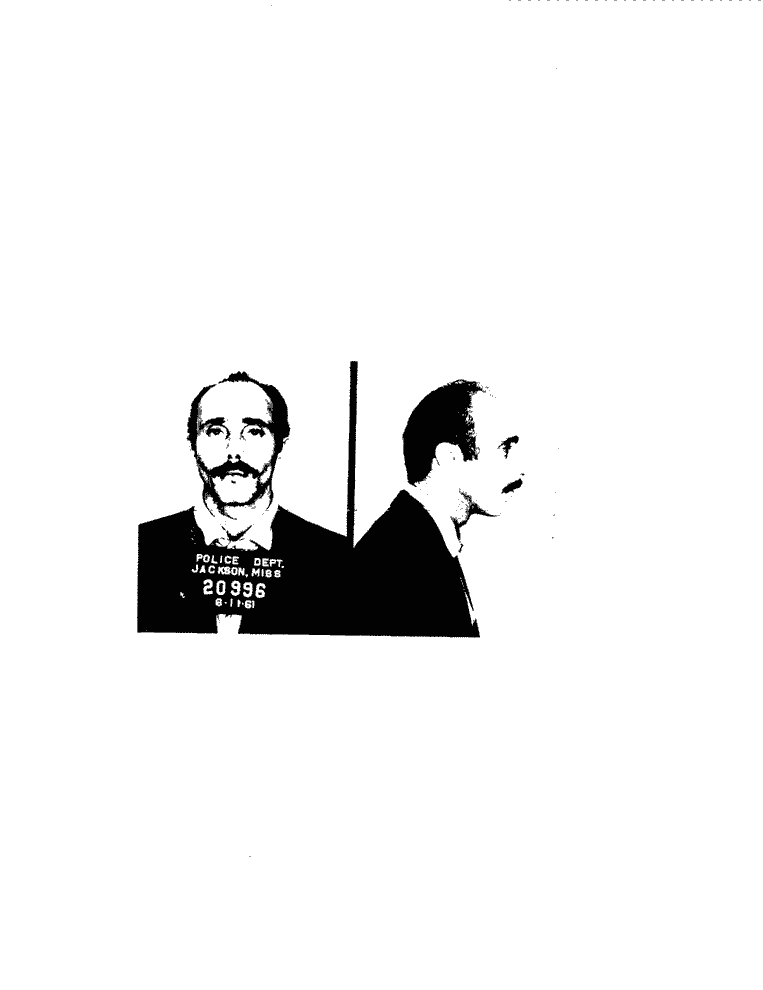

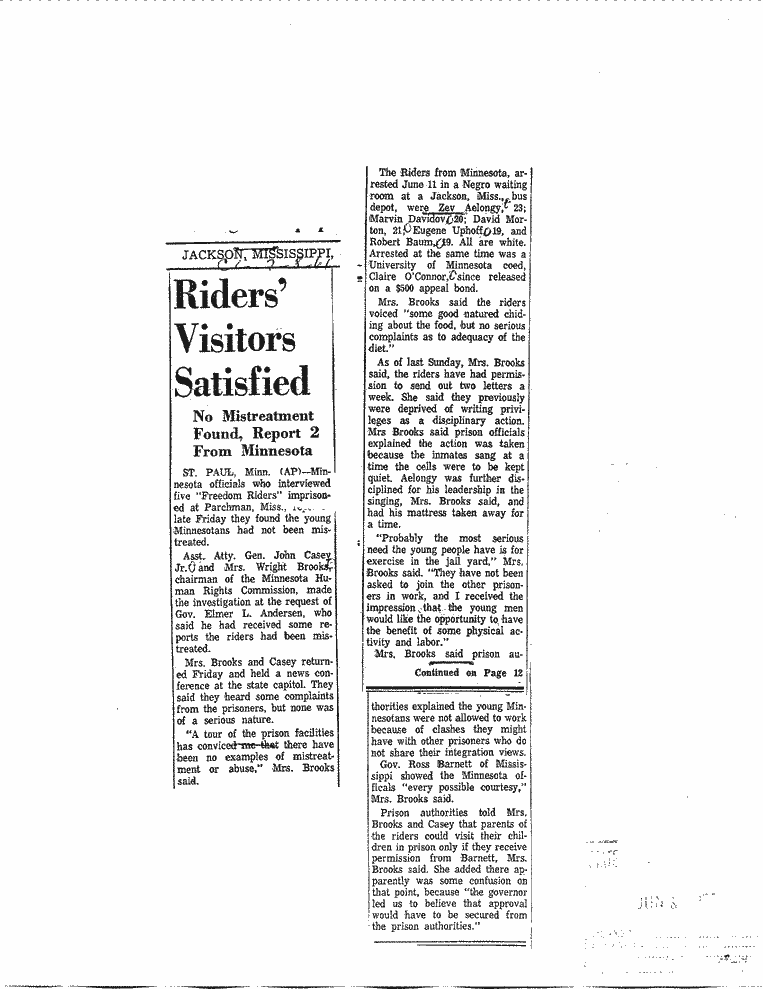

This program–which was funded by the state of Louisiana–was one of the nefarious ways that Southern white segregationists retaliated against the Freedom Rides, a protest organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) to challenge the segregation of interstate travel. Between May and November, 1961, racially-mixed groups boarded buses and traveled together through the Deep South. Greeted by police and angry mobs, the Riders risked their lives to illuminate the brutality of Jim Crow. The goal of the Riders was to use non-violent action to force a response from the federal government, which had chosen to ignore discriminatory practices in the South, despite two Supreme Court decisions that ruled these laws to be unconstitutional. More than 400 riders from 40 states ultimately participated in the Freedom Rides, including at least six protesters from Minnesota.

The year after the Freedom Rides, Singelmann and his cronies set out to demonstrate that the north was no more hospitable than the South for African Americans. They conceived the “Reverse Freedom Riders” program and recruited 200-300 African Americans to travel north.

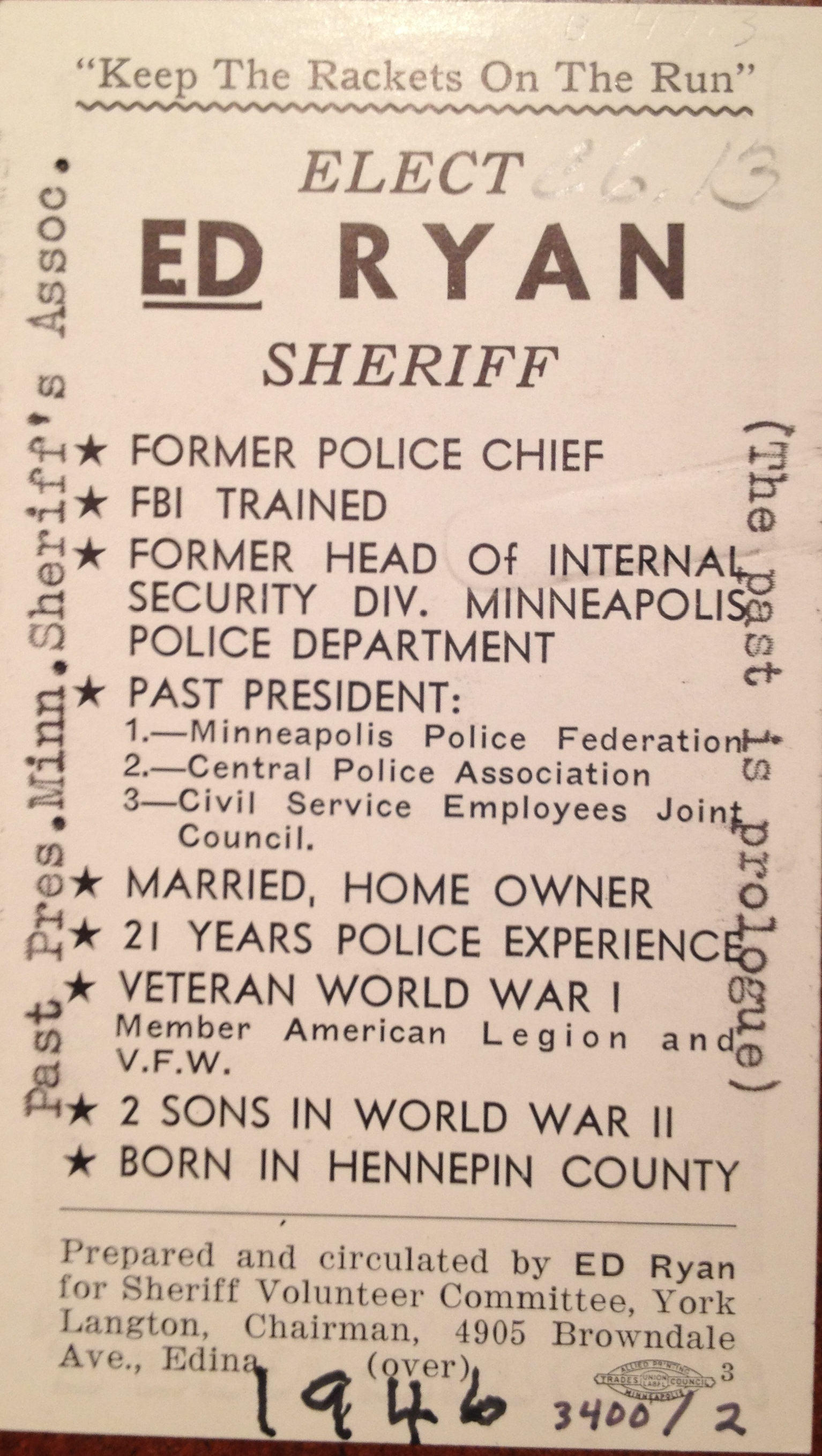

The group targeted communities that had produced supporters of civil rights. It sent migrants to Hyannis, MA because it was near President Kennedy’s family compound. It sent folks to tiny Redwood Falls, Minnesota because native son Richard K. Parsons had worked as a lawyer for the U.S. Department of Justice to ensure voting rights for African Americans in Louisiana. And in the winter of 1962–when the memo we found in the archives at City Hall was written–it focused on Minneapolis because of its association with Senator Hubert Humphrey, who had been the city’s mayor in the 1940s.

Singelmann asserted that “Senator Humphrey is the No. 1 exponent of civil rights in the nation. And we feel therefore, that it is fitting for him to have some of Louisiana’s fine Negro citizens as his dinner guest on Christmas Day.”

The White Citizen Council argued that an influx of southern migrants would show the gap between the rhetoric of civil rights and the reality of racial attitudes in the North. They selected participants they believed would “exhibit the Negroes as face-to-face examples of racial inferiority, fully justifying the philosophy of the segregationists.”

In both respects, this effort failed. Northern communities pulled together to help the people who became pawns in this segregationist scheme, providing temporary shelter and assistance. In many cases, the migrants used the free bus tickets to get out of the South and make a better life for their children.

This memo indicates that Naftalin and other city leaders were determined to thwart Singelmann and his scheme. They made preparations to assist the delegation from Louisiana. And as word spread, students at Carleton College organized a fundraiser to provide holiday meals for the migrants.

In the end, the riders never arrived in Minneapolis. But the city stood ready to ensure that Singelmann’s racist publicity stunt would flounder on the shoals of its obviously malicious intent.

Sources: “Mayor Arthur Naftalin’s Files – 1962 Commission on Human Relations,” Minneapolis City Archives, Reverse Freedom Riders Clip Flips, Minneapolis Star Tribune, Katy Reckdahl, “Reverse Freedom Rides sent African-Americans out of the South, some for good,” NOLA, May 22, 2011, http://www.nola.com/politics/index.ssf/2011/05/reverse_freedom_rides_sent_afr.html,; “South Sending Negroes As ‘Guests’ of Humphrey,” New York Times, December 4, 1962; “594 Students Forego a Meal to Aid Negroes Sent North,” New York Times, December 7, 1962.