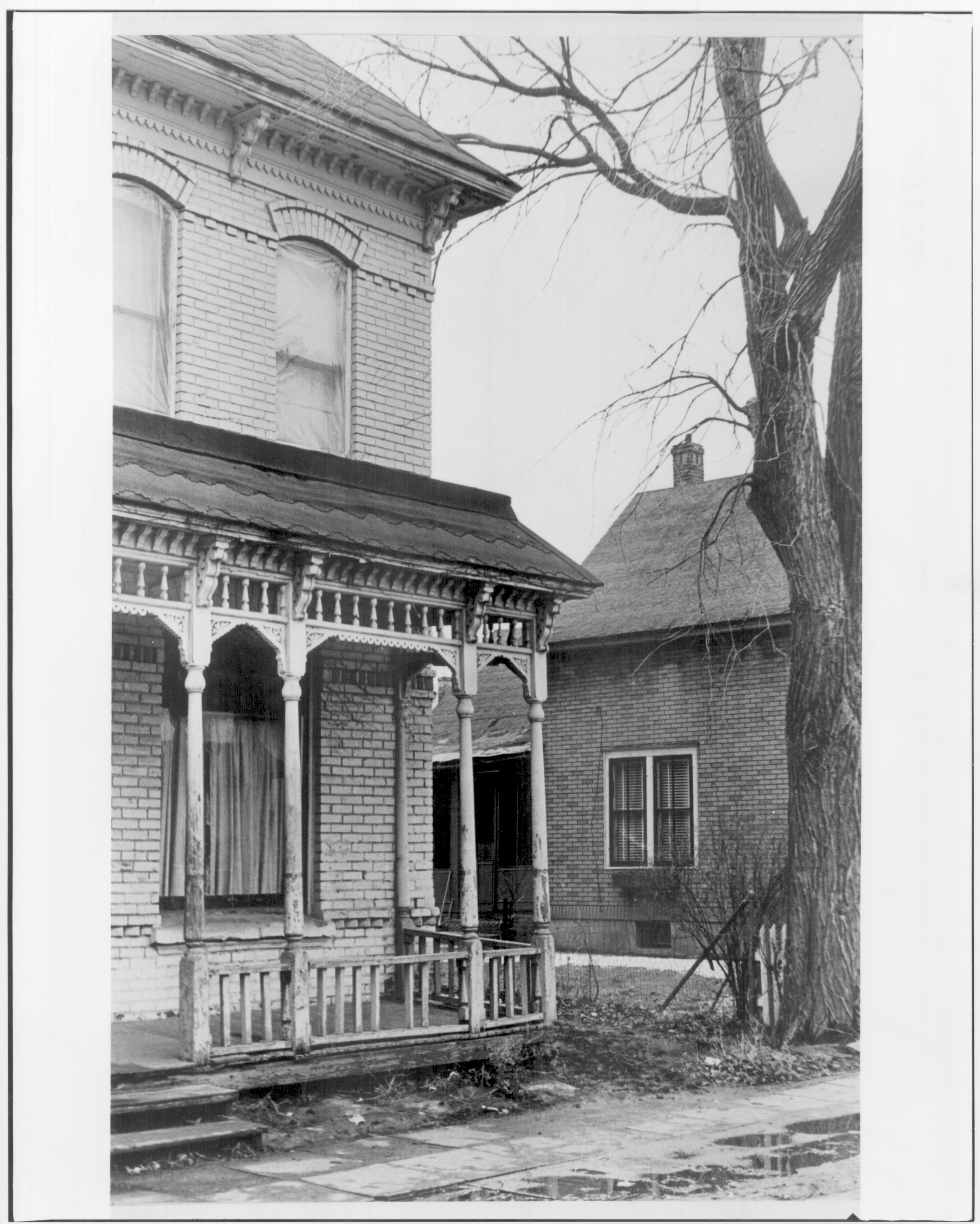

You can live in south Minneapolis your entire life and never stumble across the nineteenth century enclave that is Milwaukee Avenue, a two block development wedged between 22nd and 23rd avenues off Franklin Avenue in the Seward neighborhood. This pedestrian street–lined on either side by brick cottages fronted with gingerbread porches– transports visitors to another place and time.

These blocks were developed in the 1880s by local real estate agent William Ragan, who hoped to profit from the city’s exponential growth. He constructed the small houses to provide cheap, temporary homes for new immigrants from Scandinavia, who mostly worked in the nearby Milwaukee Railroad shops and yards. He squeezed as many structures as possible on to the narrow street, which had been originally platted as an alley. An ethnic community took shape around Ragan’s development but in these early decades no one stayed too long.

The homes were not built for the ages and they were neglected through the Depression and World War II. By 1959 the city declared its intention to see these dilapidated structures razed, pointing to the fact that at least some of them lacked indoor plumbing. But as the city sought to obtain the funds for this ambitious redevelopment plan, the neighborhood changed. And by the 1970s, Seward was home to many seasoned activists, who decided to band together to stop the destruction of this historic streetscape.

In 1974, neighborhood activists worked with the Minnesota Historical Society to get the district of workers’ homes placed on the National Register, forestalling demolition. Over the decade that followed, residents sought to preserve the street but upgrade the homes for modern families. William Rogan would likely not recognize the idyllic street today, a leafy enclave surrounded by busy thoroughfares on all sides.

In a new book–Milwaukee Avenue: Community Renewal in Minneapolis–Bob Roscoe tells the story of this campaign from his perspective as a local activist. To hear more, visit the Hennepin History Museum this Sunday at 2pm. The Museum is hosting a fireside chat and book signing with Roscoe.