Today’s guest blogger is Tamatha Perlman, a writer and museum professional, who is working on a book about murder, madness and unrequited love in 19th century Minneapolis. Tam has joined forces with Historyapolis to illuminate the holdings of the tower archives at City Hall. Here she spotlights one the thousands of burial cards in the archives from the Soldiers and Pioneers cemetery and introduces readers to notorious murderer Harry Hayward, one of the famous criminals in Minneapolis history.

Harry Hayward leaned back in his chair and vainly stroked the blond moustache on his well-shaven face. In an obvious show of disinterest, he stifled a yawn while he indictment of murder was read aloud. As the day’s proceedings came to an end, he slid on his overcoat and crossed the street to the jail. As the iron door locked Hayward into the cell, he addressed the sheriff, “I have a firstrate appetite. What have you for the bill of fare?”

Before December 1894, Harry Hayward was known around Minneapolis as a cad, a gambler and a ladies man living off of his parents’ money. Hayward had never worked an honest day, but managed to win and lose more money than most folks would see in a lifetime.

Hayward had become infamous overnight however when he was arrested for the murder of Miss Catherine “Kitty” Ging. Miss Ging was dressmaker from New York who was struggling to open her own dress shop. It was rumored that Hayward had lent Kitty money, about $9,500, to achieve her dream. As part of the deal, claimed Hayward, he took out a $5,000 life insurance policy on Miss Ging to ensure he got his money back.

On December 3, 1894, Hayward and Miss Ging met for lunch at a restaurant where Hayward made a show of handing Kitty a large roll of money, about $2,000 worth. Later that evening Kitty rented a buggy pulled by her favorite horse, Lucy and headed out alone on an errand even her closest friends were unable to pinpoint. Late that night however, as Lucy found her way back to the stables aone, Miss Ging was found laying face down near Lake Calhoun on Excelsior Boulevard. What first looked like an accidental fall from the buggy, soon became something more sinister. The coroner found a bullet piercing her skull.

As much as the city was enthralled by the murder of Miss Ging, they were more enthralled by Harry Hayward and his swaggering, unrepentant personality.He arrived each day in court, perfectly shaven and dressed in the finest attire. Early in the jury selection the papers noted that Hayward seemed well-rested and apparently well-fed, since he was starting to look a little soft around the edges. Hayward’s cool composure made police even more suspicious. He operated in court as he did playing cards. As one witness would state, “…no matter which way the game went, he did not seem to than if the chips were of no value whatever.” Not even the confession of his triggerman, Claus Blixt, could elicit a stir. But, Hayward’s pokerface began to work against him. Soon the police began pinning unsolved murders on him, not just in Minneapolis, but all over the country.

The day before his hanging Hayward confessed to several murders, saving the murder of Miss Ging for last.”Throughout there was not a word that might be construed as contrition or sorrow for what he had done. It was the outpourings of a criminal who was only sorry that his career of crime had been checked so soon, for it had been his ambition to be the prince of criminals of his day,” wrote the Tribune on the day of his execution

Hayward ascended the gallows which had been painted red per his request, dressed in a cutaway coat and high collar. After a brief speech, he addressed the executioner. “Pull her tight. I’ll stand pat!”

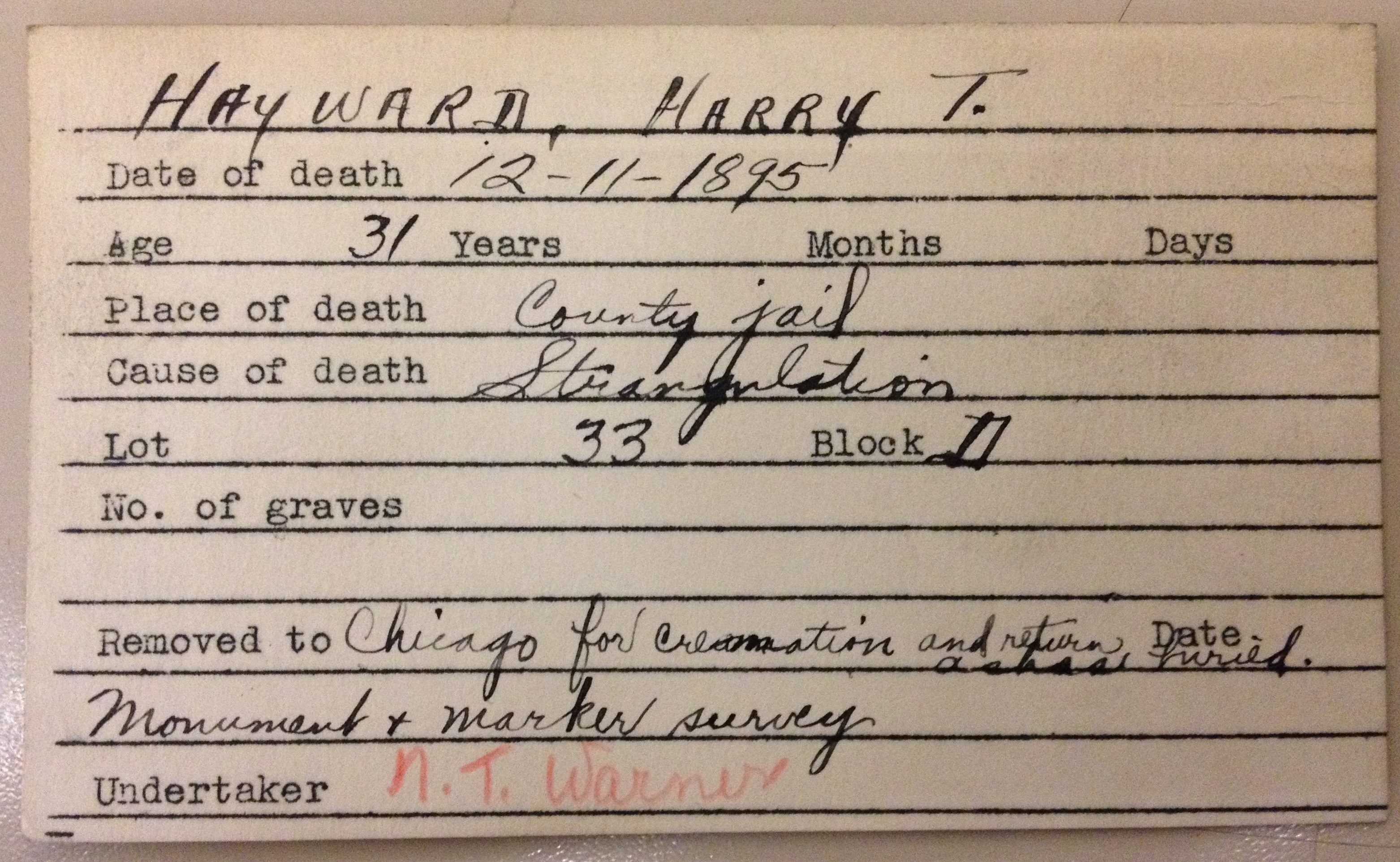

A brief autopsy was performed on Hayward. The coroner confirmed that Hayward’s skull that the unusual thickness of his skull confirmed a mental illness that had created his heartless demeanor. Hayward was then taken by train to Chicago so that his remains could be cremated. Upon his return he was buried at Soldiers and Pioneers cemetery.

Burial card is from the index to the Soldiers and Pioneers cemetery at the tower archives, Minneapolis city hall.