Nineteenth century women’s fashions were rather impractical for life in Minnesota. In 1914, a woman who had arrived as a young girl in Minneapolis in 1856–two years before Minnesota became a state–remembers the challenges of winter when you had to wear a hoop skirt, like the two women pictured above. She told the Book Committee of the Daughters of the American Revolution that:

“No one who was used to an eastern climate had any idea how to dress out here when they first came. I wore hoops and a low necked waist just as other little girls did. I can remember the discussion that took place before a little merino sack was made for me. . . I must have looked like a little picked chicken with goose flesh all over me. Once before this costume was added to, by the little sack, my mother sent me for a jug of vinegar down to Helen Street and Washington Avenue South. I had on the same little hoops and only one thickness of cotton underclothing under them. It must have been twenty degrees below zero. I thought I would perish before I got there, but childlike, never peeped. When I finally reached home, they had an awful time thawing me out. The vinegar was frozen solid in the jug.”

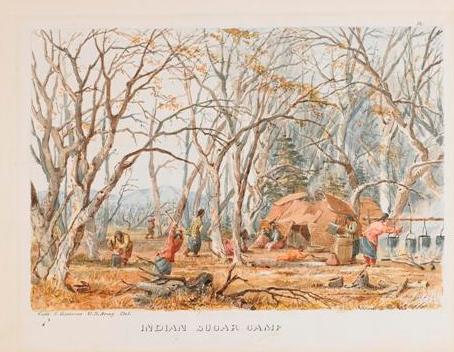

Interview with Mrs. Charles Godley (nee Scrimgeour) for Old Rail Fence Corners, the ABCs of Minnesota History, which was put together by the historians of the Daughters of the American Revolution. The image of two women was taken in 1860 and is from the Minnesota Historical Society.