Today’s blogger is Anna Romskog is a junior history major at Augsburg College. She will be a regular presence here during 2014, when she will be working as one of the student researchers for the Historyapolis Project.

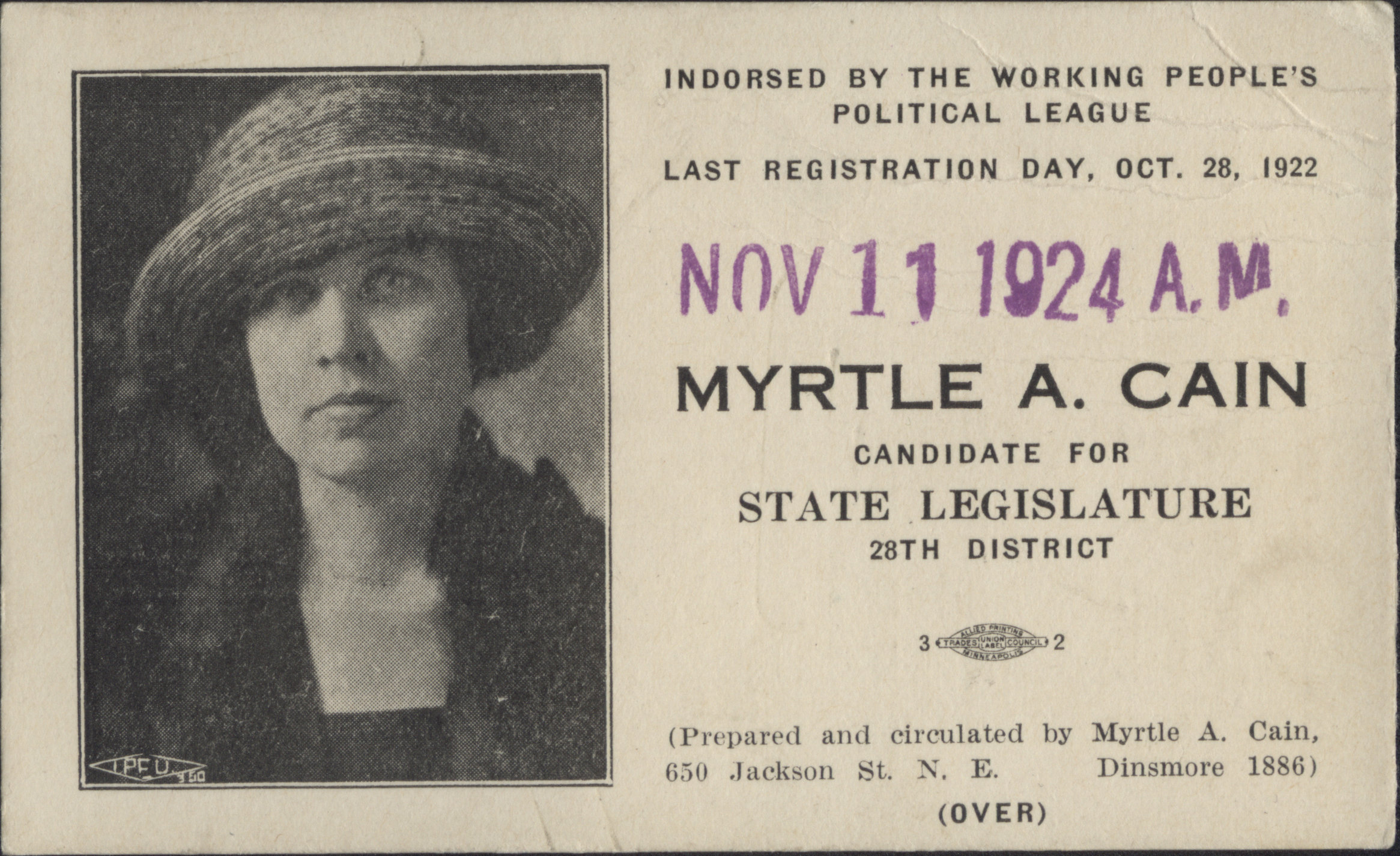

This card–from 1922–urges voters in the 28th district of Minneapolis to vote for Myrtle A. Cain, a candidate for the Minnesota State Legislature who was “indorsed by the Working People’s Political League.” Cain was one of the pioneering political women who immediately sought public office after American women were granted the vote by the Nineteenth Amendment.

In 1922, Cain was one of four women to win seats in the Minnesota state legislature. When she went to St. Paul, she represented a constituency in Northeast Minneapolis that was dominated by immigrants and labor activists like herself.

Before running for office, Cain developed her leadership skills in the labor movement. Cain organized a strike of “Hello Girls” or telephone operators that started in November of 1918, just a few days after the Armistice ended World War I. Under Cain’s leadership, the strikers demanded significant wage increases and better working hours, mounting a bold though ultimately unsuccessful challenge to the local business elite.

At the same time Cain pledged her support to the National Woman’s Party, a radical feminist group organized in 1917 to win full equality for women. The NWP staged dramatic, non-violent protests to demand the immediate enfranchisement of women; after the Nineteenth Amendment it launched a campaign for a measure it called the Equal Rights Amendment, a constitutional amendment that would mandate equal treatment for both sexes under the law.

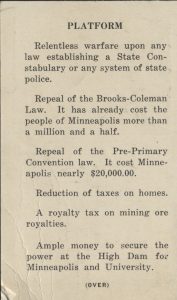

Cain’s activist history shaped her legislative priorities when was took her seat at the State Capitol. She was one of a handful of legislators to support the Granting Equal Rights, Privileges, and Immunities to both Sexes bill. The bill, supported by Cain and six male legislators was not a popular one and was opposed by the three other women who were legislators during the 1923-24 session, including well-known suffragist Clara Ueland. The other three women worried that Cain’s bill was too radical and would erode the political gains just won by women. The vote on the bill was postponed indefinitely. Cain detailed the rest of her agenda on the back of her campaign card:

Much to the relief of more conservative female legislators like Mabeth Hurd Paige, Cain did not win her bid for re-election in 1924. She lost by just 39 votes to John F. Bowers, also of the Farmer-Labor Party.

This set-back did little to dampen her conviction that women deserved equal protection under the law. In 1973–when Minnesota was considering whether to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment–Cain returned to the State Capitol to speak in favor of the measure.

Cain’s voter card is from the vertical files at the Minneapolis Collection, Hennepin County Central Library. Material for this post is taken from Elizabeth Faue, Community of Suffering and Struggle: Men, Women, and the Labor Movements in Minneapolis, 1915-1945, (University of North Carolina Press, 1991); Mary Pruitt, Myrtle Cain (1894-1980) in The Privilege for Which We Struggled: Leaders of the Woman Suffrage Movement in Minnesota, ed. Heidi Bauer, (St. Paul:Upper Midwest Women’s History Center, 1999); Darragh Aldrich, Lady in Law: A Biography of Mabeth Hurd Paige (Chicago: Ralph Fletcher Seymour, 1950).