The month we now devote to women’s history was traditionally dedicated to maple sugaring for Dakota and Ojibwe women. The beginning of meteorological spring sent Indian men in search of muskrat pelts. They separated from their women and children, who moved their camps into the sugar bush. These camps labored to create enormous stores of maple sugar, which would sustain the community for the rest of the year. In good years, they were able to make enough for their own consumption and extra to trade. Women could exchange maple sugar for the manufactured goods that had transformed their lives in the early nineteenth century.

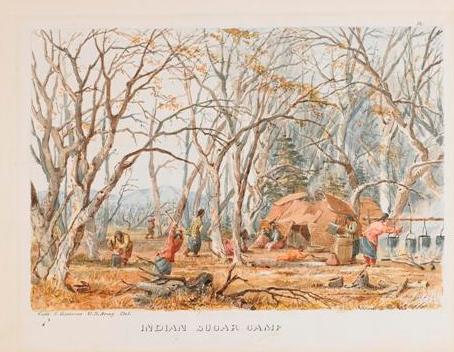

Most critical for women were the kind of metal kettles pictured here, in this 1845 watercolor by Army officer Seth Eastman. Normally used for routine cooking, these pots were filled with sap in March. The sap boiled for days until it was reduced to sugar, which could be packed into birch bark containers. These served as early Indian tupperware.

Maple sugar was an important dietary supplement for everyone in the region. According to the explorer Henry School craft, it was “profusely eaten by all of every age,” leading to enormous problems with tooth decay. Sugar consumption increased with the advent of the fur trade, when newcomers brought both metal kettles and an expectation that their food would be sweetened. Pots made large scale sugar production possible. And Indian women cornered the market on maple sugar; local cravings for sweets were satisfied by their hard labors and planning every spring.

In the area that became Minneapolis, Dakota women made annual pilgrimages to sugar bush groves located on Nicollet Island and near Minnehaha Falls. In these spots, proximity to the Mississippi River ensured that trees had the moisture they needed to create a steady stream of sap. Early reports describe how soldiers sometimes tried to push women out of these choice locations, in an effort to seize control of this valuable local commodity. In 1829, the Dakota protested to Indian agent Lawrence Taliaferro. “You my Father promised not to let any person interfere with a Small piece of ground where our women go sometimes make a little Sugar,” they asserted. “You promised us this.”

Information on maple sugaring in Minneapolis is from Bruce White and Gwen Westerman’s Mni Sota Makoce: The Land of the Dakota (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2012): 97-98. This watercolor was created by Seth Eastman and might depict the Nicollet Island sugar bush in the winter of 1845.