On Saturday morning, Historyapolis will again team up with James Eli Shiffer to lead a Preserve Minneapolis tour of the lost Gateway district of Minneapolis. This will be our third year doing the tour, which poses some challenges since we have to re-create a world that no longer exists. To be successful, this expedition into the past demands the active participation of tour-goers, who have to make heavy use of their historical imaginations. If you’re willing to do some work and some walking, click on this link and join us for the fun.

For some people at least, the effort is worthwhile. This lost world holds riches for anyone interested in understanding the city in all of its seamy complexity.

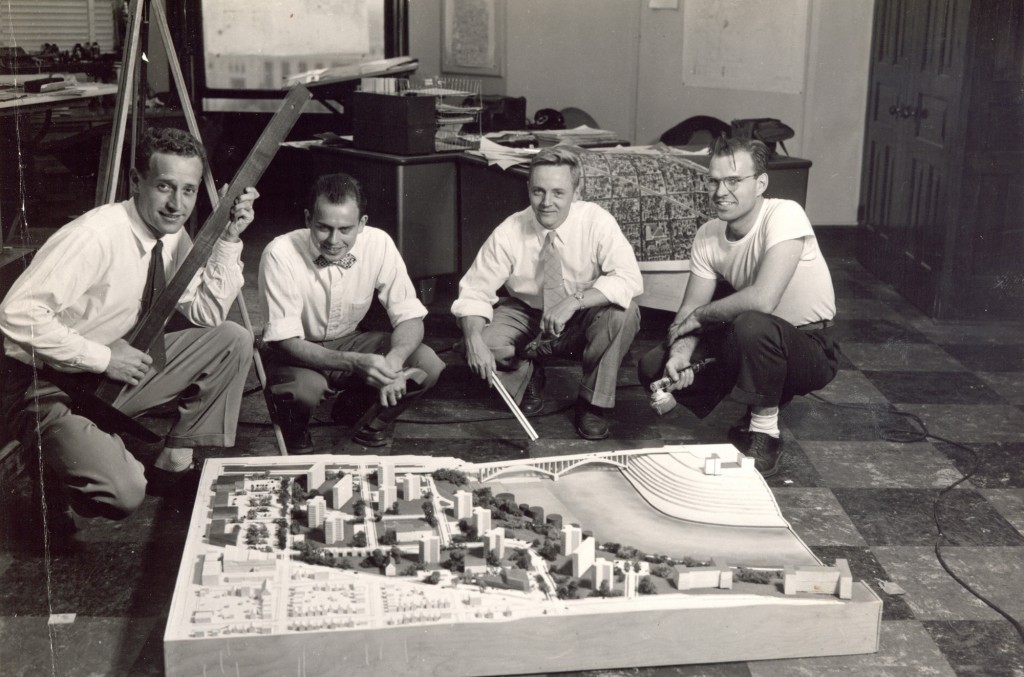

The infamous Gateway, which became the region’s largest skid row around World War I, began to disappear under the bulldozers in 1959. That was the year the city launched its massive, federally-funded effort to redevelop downtown. When the dust settled, the city had flattened 40 percent of the central business district. City planners envisioned a futuristic cluster of skyscrapers rising from the rubble.

Some new, modern buildings did appear, like this structure constructed by the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance company. Designed by Minoru Yamasaki, who also was the architect of the World Trade Center in New York City, it was the pride and joy of the city’s urban planners.

Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Building, CPED collection, Hennepin County Library Special Collections.

But the clear-cut area was dominated by surface parking lots which are only now starting to be developed, more than 50 years after the wrecking balls did their work.

Before it was flattened, the district was known for everything that city boosters hated. Minneapolis was built on a river and tied to the power of water. But its founders imagined it as a “city on a hill”: a model metropolis with no urban problems. This civic ideal persisted, despite the regular intrusion of reality. But it was the Gateway–perhaps more than anything else –that constantly challenged the city’s claim to be an urban paragon.

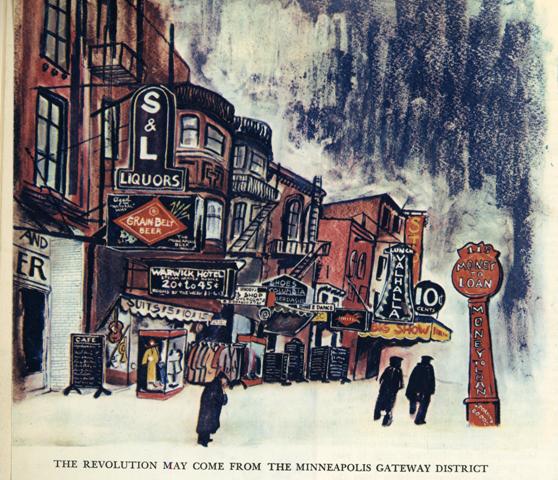

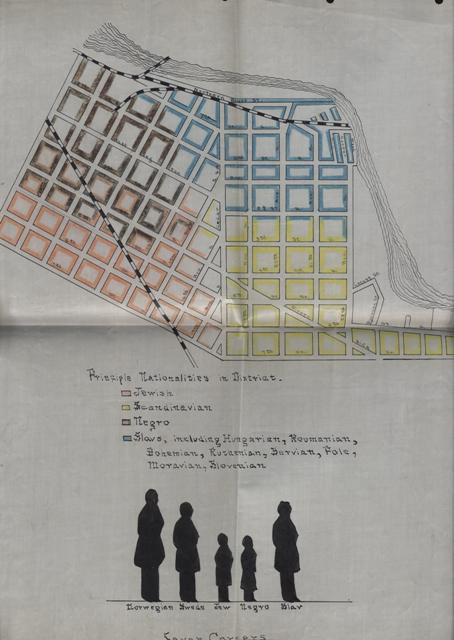

In the historic heart of the city, the alcohol flowed freely, the idlers wiled away their days in the park and on the sidewalks; the prostitutes were brazen; men sought sexual encounters with other men; the buildings were dilapidated and vermin-ridden; the communists and Wobblies called for the overthrow of capitalism and the American political system. Its flophouses sheltered people not welcome elsewhere. In these squalid conditions, a community took shape that included exhausted lumberjacks and harvest hands; alcoholics wanting to drink out their last years in peace; Chinese men seeking respite from West Coast racial violence; Native Americans looking for anonymity in the big city.

During the Great Depression, the district drew journalists and photographers who wanted to document the human suffering of the economic crisis. Photographers from the Farm Security Administration–like Russell Lee who shot the image of men in Gateway Park that is featured at the top of this post–immortalized Gateway denizens as the urban counterparts to Dorothea Lange’s migrant workers. And when a reporter from Fortune magazine visited the city in 1936 to investigate the origins of the Truckers’ Strike, which had been organized by Trotskyites but supported by thousands of working-class Minneapolitans, he concluded it was from the Gateway that “the revolution” so feared by many Americans “would come.”

The Gateway distilled the city’s social problems, concentrating them in a few overcrowded blocks that offered adventure, oblivion and community. Here was everything the city wanted to hide. Which is why a close examination of this one neighborhood reveals so much about Minneapolis.

It is this symbolic power of the Gateway that fascinates me. But for James, it is the culture and stories of Skid Row that draws him to this lost world. He has just completed a new history of the Gateway–which will be published by the University of Minnesota Press–that uses vivid storytelling and description to transport readers to this world in its twilight moments. The narrative centers on the life of John Bacich, aka Johnny Rex, the self-appointed “King” of Skid Row. Bacich owned a bar and liquor store and flophouse in the Gateway. He also had a documentary impulse and shot home movies of these venues right before they were demolished. This footage was incorporated into a 1998 TPT documentary which James happened upon several years ago. Inspired to track down Bacich, James spent three years interviewing him before his death in 2012.

Beyond the Bacich footage, there is rich visual documentation of the Gateway, which has attracted generations of artists, documentarians and city planners. Over the course of the week to come, I’ll share some of my favorite of these images, which never fail to transport me to world that is utterly foreign to modern Minneapolitans.