Guest blogger today is Sara Strzok, a medical writer and editor based in Minneapolis.

Like so many women of her era, Eloise Butler (1851-1933) worked on the margins – in her case, both socially and geographically – to get what she wanted. In 1907, she joined the ranks of Minneapolis Park Board visionaries like Theodore Wirth and Charles Loring when she saw the fruition of her plan to create and preserve the first wildflower garden in the nation. What’s now called the Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden and Native Bird Sanctuary is a microcosm of Minnesota meadow, hills and bog flora at what was then the edge of town. Her teaching career and her campaign for this invaluable wild space at the margins of the city foreshadow the concerns of educators and environmentalists today.

Though a keen and observant scientist who made significant contributions to the field of natural history (three species of algae she discovered are named in her honor), barriers common to women in academia at the time kept her from advanced training and a career as a research scientist. Instead, she supported herself through teaching. As Butler pointed out in a brief autobiographical sketch, “at that time and place no other career than teaching was thought of for a studious girl.” A native of Maine, Butler was educated at teacher colleges in the east and moved west with her family to teach in Indiana. She moved on her own to Minneapolis when the well-paid teaching positions in modern, comfortable buildings advertised by the growing city appealed to her more than the onerous life of a one-room schoolhouse teacher. She taught at several schools, including Central and South high schools.

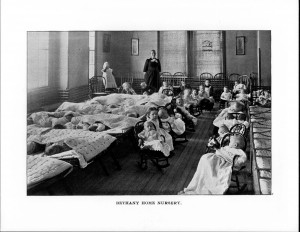

During her 38-year career, she coped with the same issues that face Minneapolis educators today. Overcrowding forced schools to use stairwells as makeshift classrooms; school days were conducted in shifts while the school board debated building new facilities. Many of her students were immigrants who did not yet speak English. In her writings, Butler described her summer research trips to Jamaica, Woods Hole, and a short-lived University of Minnesota marine research center on Vancouver Island as bright spots in the round of drudgery that was teaching. She put the “sounds of the schoolroom” at the top of a list titled “My Hates” and noted that “In my next incarnation I shall not be a teacher.”

Despite this problematic relationship with her career, Butler was a popular, effective and influential science teacher. She was passionate about connecting children to nature in a way that foreshadows the current farm to fork trend in education of groups like Youth Farm, which cultivates summer gardening programs for children. Butler judged the summer garden she ran at Rosedale Elementary School (43rd Street and Wentworth Avenue) a success when children told her that their harvest “tasted much nicer than any that could be bought of the grocer.” Butler advocated for greenhouses connected to schools (a dream realized at Central High School’s new building after her retirement) and for her wild garden, saying, “knowledge of the soil and its products … would do much toward shielding young people from the temptations of artificial and unhealthful amusements of city life and lead them back to nature where the mind and body could develop in a healthful and sane way.”

Though Butler used typically feminine modesty and language in her campaign for the wildflower garden (all work done at the garden by female botany teachers was conducted, of course, “under the direction” of park work men), she was opinionated and uncompromising in her advocacy for saving wild spaces from thoughtless development, using language that sounds familiar to us today. In fact, she objected to the term “wildflower garden,” preferring instead “native plant reserve.” Her screed against suburban gardeners could come from today’s headlines about battles between environmentalists and lawn-proud lake dwellers:

Cottagers on the suburban lakes have fettered ideas of planting that are more appropriate for city grounds, and condemn their neighbors, for a lack of neatness in not using a lawn mower … apparently dissatisfied until the wilderness is reduced to a dead level of monotonous, songless tameness.

When she retired from teaching, the Minneapolis Park Board hired as the first curator of the native plant reserve she founded at a salary of $50 per month, less than most groundskeepers made. She held this position until her death in 1933. She described these retirement years as the most professionally fulfilling of her life – but again, most of her work was done on the margins of the professional research world. She paid out of her own pocket to fence the grounds to protect specimens from collectors and vandals. She was unable to get University of Minnesota sponsorship and funding for the truly groundbreaking collection of native plants she curated because she lacked professional credentials. Instead, she relied on her own efforts and those of her friends and fellow amateur botanists. While it has less biodiversity than in Butler’s time, the garden still hosts more than 500 plant species and 130 bird species in woodland, wetland and prairie areas

At my last visit to the wildflower garden, I found myself ruefully wondering how different the landscape of Minneapolis might look if Eloise Butler had a professional scientific career, instead of exercising her passion on the margins. Would this garden exist?

Material from this post is taken from the Friends of Eloise Butler website; M. E. Hellander, The Wild Gardener: the life and selected writings of Eloise Butler; and E Butler, “Back to Nature: A little patch of God’s creations in connection with school studies,” The Labor Digest (1908).

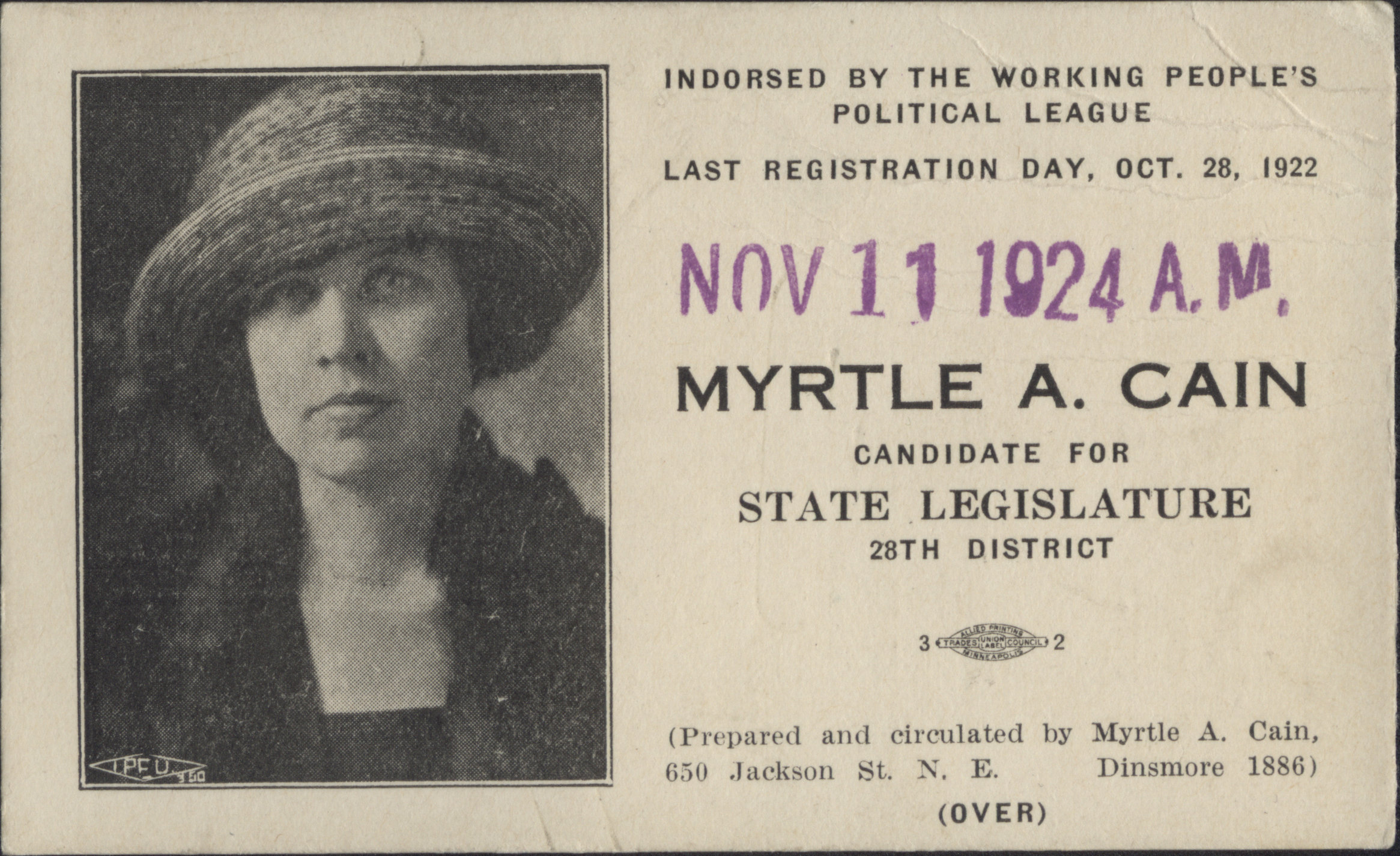

The photo shows Eloise on her 80th birthday with a group of friends. It is from the Hennepin County Libraries Special Collections.