Happy Halloween. This haunting photo captures an unconventional commemoration of this day almost 100 years ago. Patients at Hopewell Hospital in North Minneapolis donned masks and witches’ hats, readying themselves for what appears to have been a somber party. Their day would not have been enlivened by any visitors. For these unsmiling jesters and grim-looking Indian chiefs, Halloween in 1917 was just another day in quarantine.

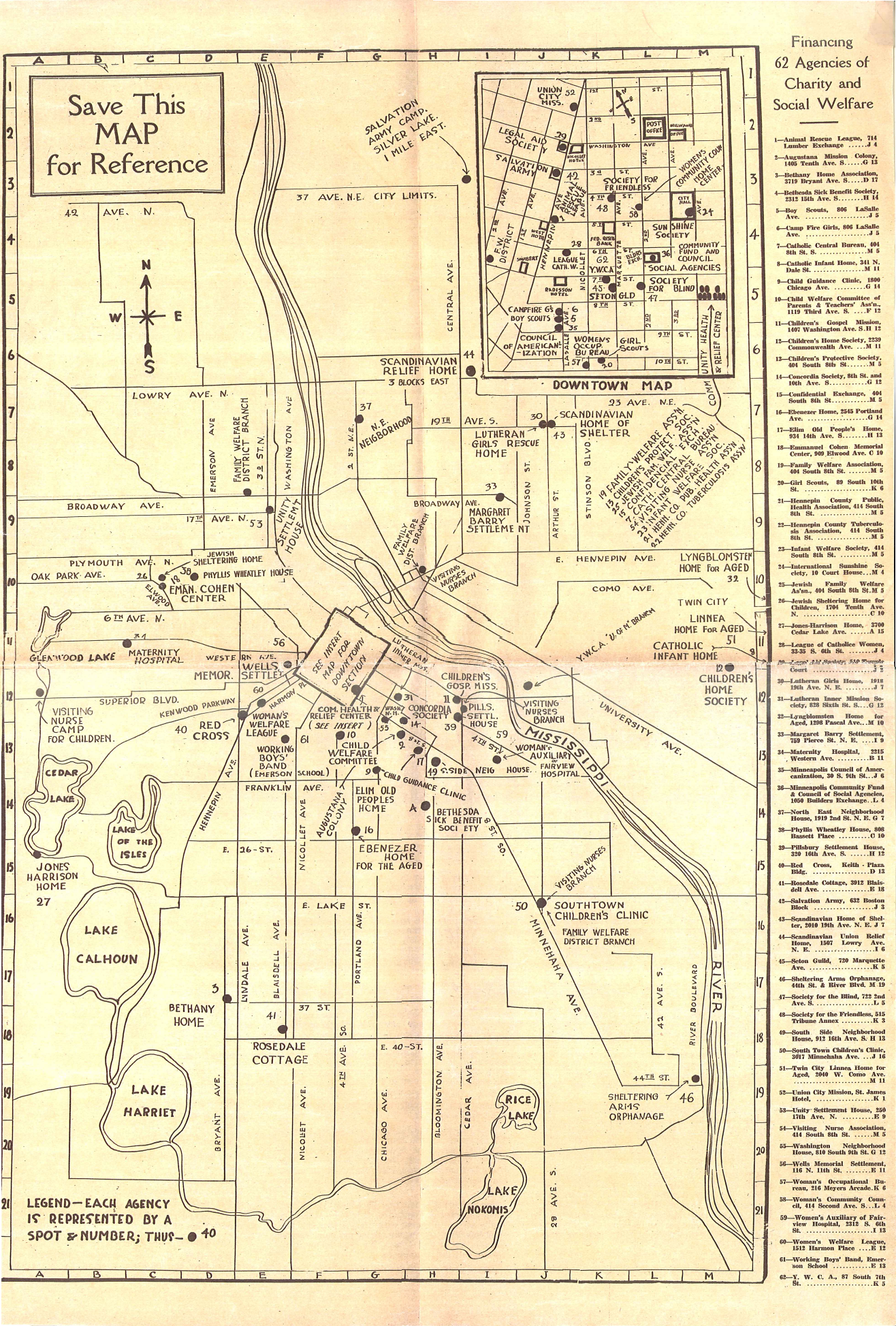

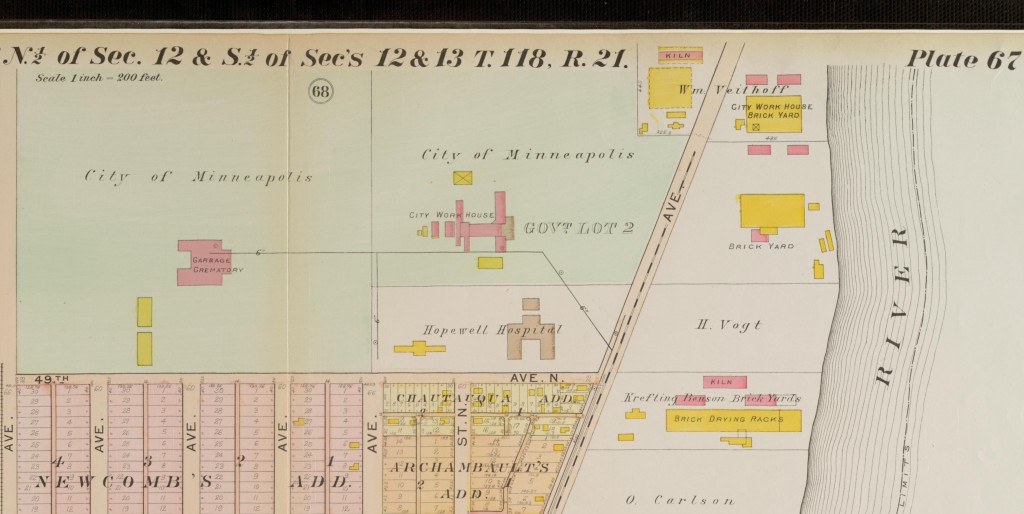

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Hopewell Hospital was the Minneapolis tuberculosis sanatorium. Situated in an isolated industrial quarter of the Camden neighborhood, the hospital looked out over city workhouse, the garbage “crematorium” and the brick works on the Mississippi River.

The Minneapolis plat map from 1914 shows Hopewell Hospital and its environs in the Camden neighborhood of North Minneapolis. The TB facility overlooked the “Garbarge Crematorium,” City Workhouse and brick yards. Map comes from the Special Collections of the Hennepin County Libraries.

Established in 1907, the facility housed the city’s tuberculosis sufferers, who were seen as an acute threat to the community. A bacterial infection that attacks the lungs and is easily transmitted through air droplets, tuberculosis was a common and deadly killer in these days before life-saving antibiotics. It spread easily in the overcrowded quarters of American urban neighborhoods. Tens of thousands of Minnesotans died from TB in the thirty years before these clowns and witches posed for the camera.

Thanks to the recent outbreak of Ebola, Americans are grappling anew with the question of quarantine. Though less common today thanks to widespread vaccinations and highly effective antibiotic treatments, the practice of quarantine was routine when this image was created. In the United States, local governments had imposed quarantines since the eighteenth century. Starting in the late nineteenth century, federal authorities had played an ever-larger role in this process, focusing their efforts on quarantining individuals with tuberculosis, cholera, diptheria, plague and yellow fever. Hopewell housed only TB patients. Minneapolitans with smallpox were brought to another facility located in present-day St. Louis Park, where the survival rate was very low.

Hopewell treated TB patients until 1924, when Hennepin County decided to bring all sufferers of this disease under the same roof at Glen Lake Sanatorium in modern-day Eden Prairie. Hopewell Hospital became Parkview Sanatorium and continued service as a public charity hospital until the building was eventually razed.

A Halloween photo from the closed ward of a TB sanatorium may be the stuff of nightmares for some viewers. Or inspiration for a new gothic novel by Ransom Riggs set in the post-industrial landscape of the Minneapolis north side.

But this image ultimately strikes me as more poignant than terrifying. We have no way to know the real identities of the woman posing as a gypsy fortune teller or the man attired like Uncle Sam. The fates of these patients–and the question of whether they survived their encounters with this deadly bacteria–will remain a mystery.

The day after Halloween–known in Mexico as the Day of the Dead–might provide an opportunity to remember this group of Minneapolitans. On Saturday morning we could amble through North Mississippi Regional Park in search of traces of Hopewell hospital, thinking about family and friends no longer with us. And take a moment to reflect on the myriad connections between the living and dead in our city.

The photo is from the Hennepin County Medical Center Museum Collection via the Minnesota Digital Library. The detail from the 1914 plat map of Minneapolis is from the Minneapolis Collection at Hennepin County Libraries Special Collections. Special thanks to librarian Ted Hathaway for providing Historyapolis with a high-resolution version of this image.