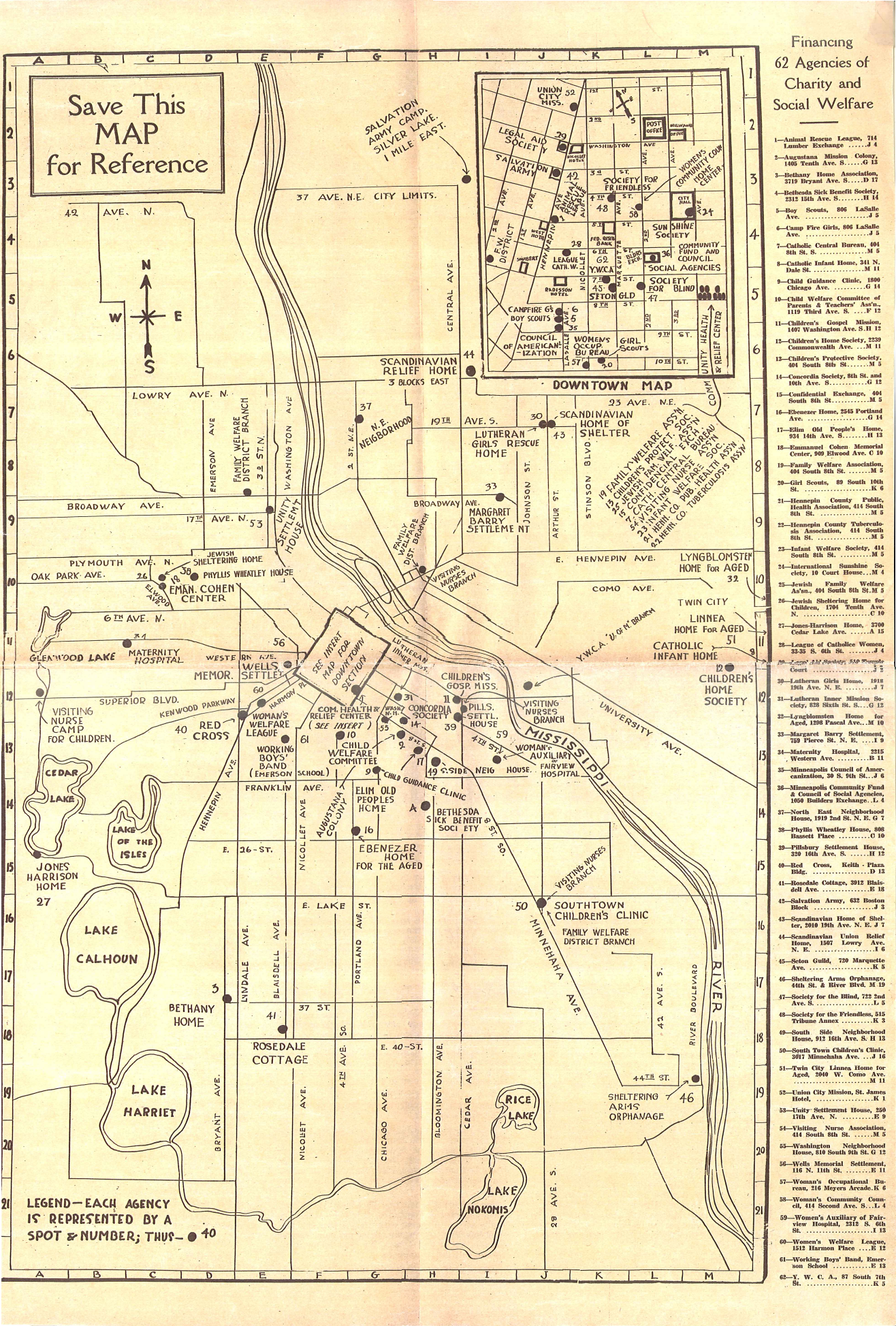

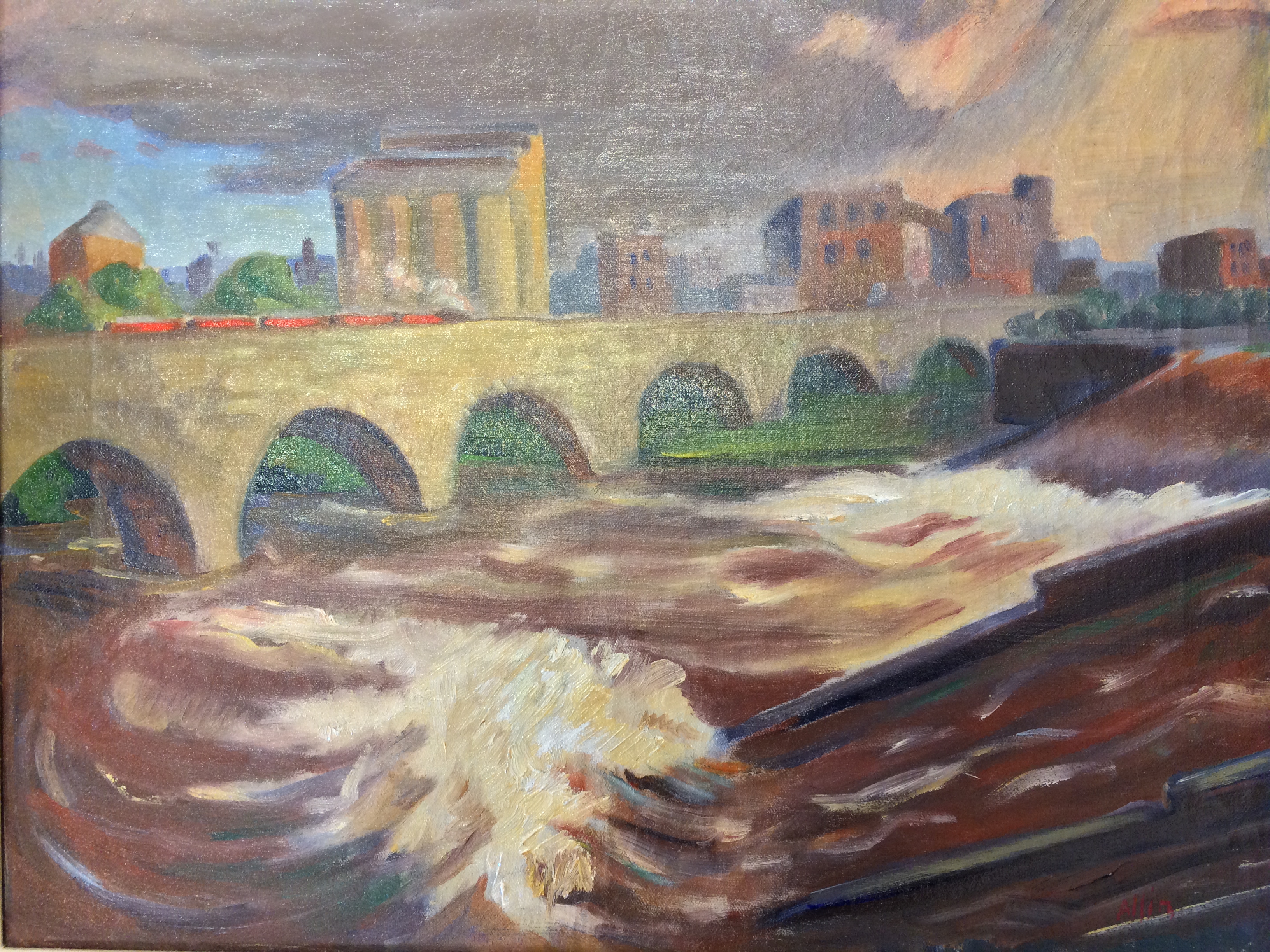

After a summer hiatus, Historyapolis is returning to regular programming. Since it’s map Monday, today we’re featuring a map of “Charities and Social Welfare” in Minneapolis from the Social Welfare History Archives at the University of Minnesota.

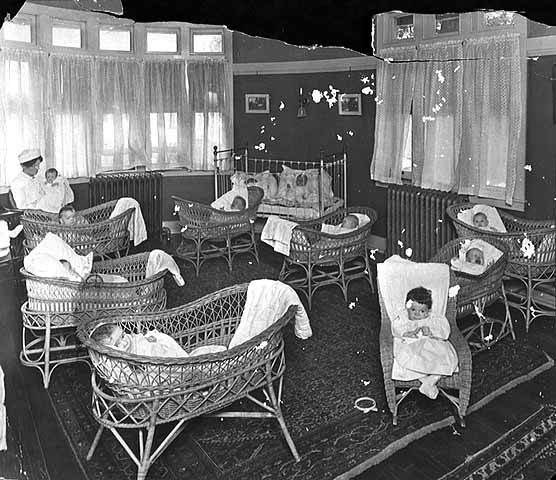

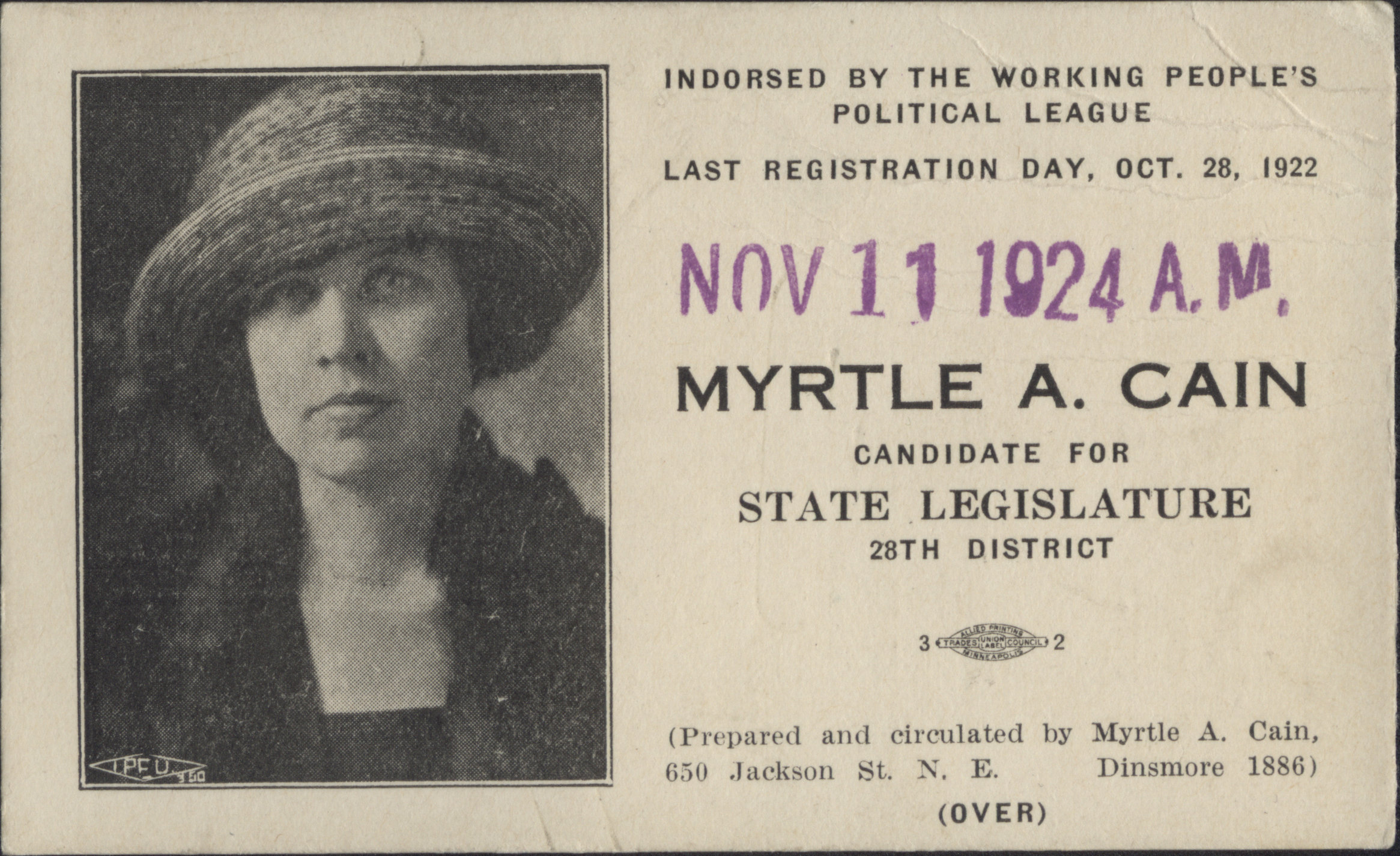

This diagram maps the provision of private aid to Minneapolitans in the second half of the 1920s, showing the location of 62 private aid organizations. The exact date of this map is unknown, but we know it was created after 1924, when the Phyllis Wheatley House was established and before 1929, when the YWCA moved to a new building on Nicollet Mall. In addition to the Wheatley House and the YWCA, the map includes the Maternity Hospital established by Martha Ripley and the Bethany Home for “fallen women” conceived by Charlotte Van Cleve, Harriet Walker, Euphoria Outlook and Abby Mendenhall. It shows the city’s settlement houses and its public homes for the impoverished elderly. It indicates the locations of orphanages; non-profit employment agencies; homeless shelters and missions; and even the Legal Aid Society, which gave free legal advice to workers embroiled in wage disputes.

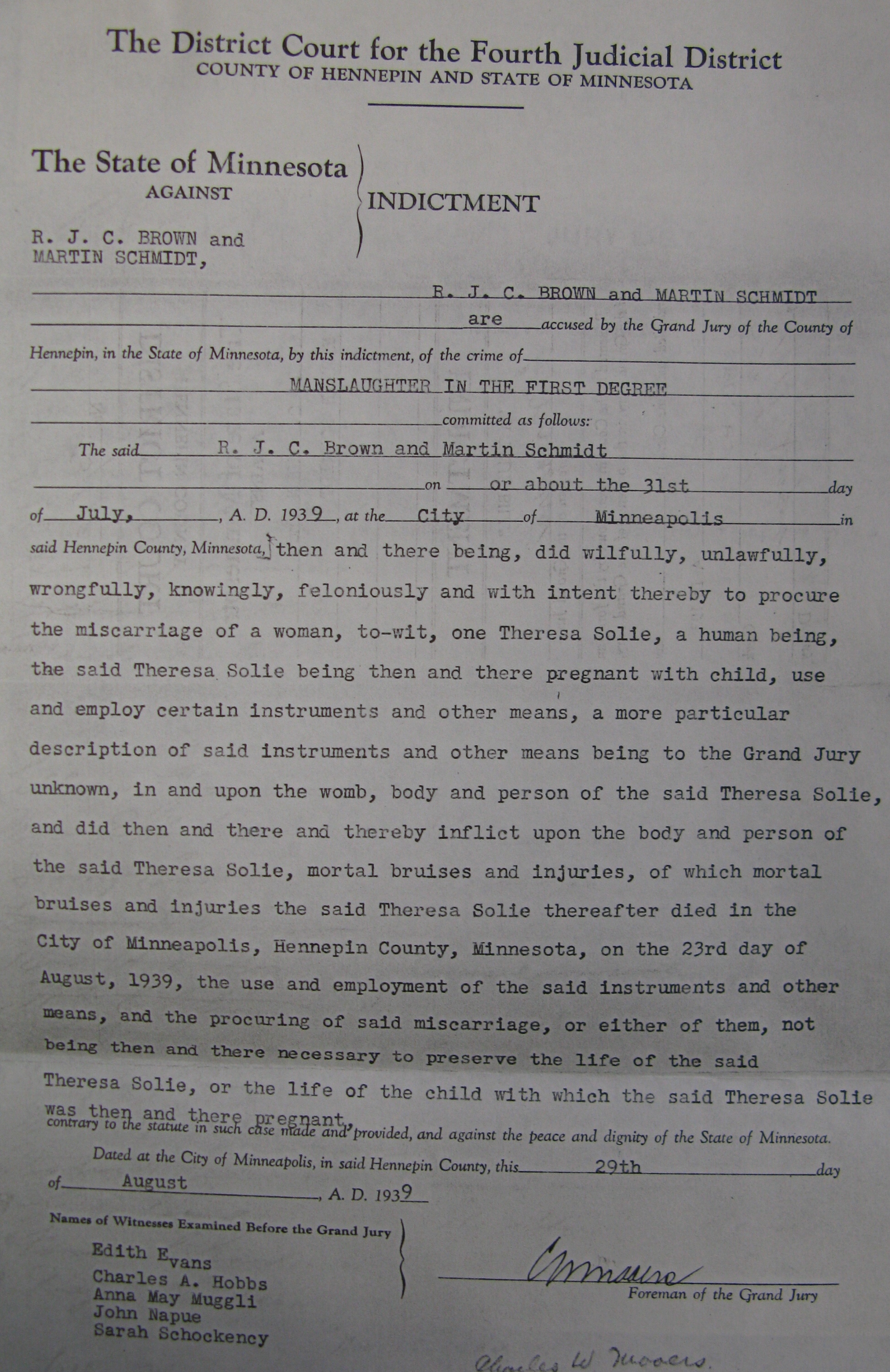

In the decade before the Great Depression, the city had little in the way of “public” or government-funded charity or welfare programs. Instead, city residents were served by the network of private charitable associations shown here. Between the 1880s and the 1920s–as the population of the city expanded exponentially–concerned Minneapolitans created these myriad organizations to address the hardships created by urbanization, immigration and industrialization. The needs were overwhelming. The city lacked decent affordable housing and had little in the way of sanitation services; children wandered the streets; working people struggled to maintain their health and their employment. These groups–which varied in focus, purpose and philosophy–struggled to make the urban environment more liveable and humane, paying particular attention to the welfare of vulnerable women and children.

The organizations shown here were likely linked by a common association with the Community Fund of the Council of Social Agencies, which ran a fund-raising campaign for associated social welfare groups in the city. This map was likely created by this group as a resource for both donors and social workers.

Created at the behest of the business community, the Council was animated by the principle of “scientific charity.” Business leaders were instrumental in championing this philosophy, which called on social welfare agencies to work together to prevent duplication of efforts and connect deserving individuals to the services they needed most. This coordination had a darker side as well. Proponents of scientific charity were focused on ensuring that recipients did not lose their will to work and did not game the system, drawing aid from multiple sources.

The landscape of private charity was transformed by the onset of the Great Depression, which threw one-third of the city out of work. This crisis overwhelmed private charity, which could not meet the overwhelming needs of the city during that decade. This economic collapse prompted the creation of a series of government welfare programs, which now work hand-in-hand with many of these same groups to address–but never satisfy–the social needs of the community.

Image credit: Linnea Anderson, Social Welfare History Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries.