Today’s guest blogger is Penny Petersen, the author of Minneapolis Madams and a researcher for a Minneapolis-based historical consulting firm.

The Homewood neighborhood adjacent to Theodore Wirth Park has been called one of the “best-kept secrets” of Minneapolis. Yet more often, the subdivision of impressive homes constructed in the first decades of the twentieth century has been described as a neighborhood with “an ugly beginning.” In her critical history of urban development in Minneapolis, legendary geographer Judith Martin enshrined a popular myth about the neighborhood. According to Martin: “Covenants attached to each piece of property specifically prevented parcels from being sold to Jews.”

There is one problem with Martin’s assertion. No trace of any racial or religious restrictions can be found in the property records. After examining dozens of original Homewood deeds at the Hennepin County Recorder’s Office scattered over all 20 blocks of the addition, I did not encounter one clause that barred owners from selling their property to Jews or African Americans.

This subdivision–platted in 1909–was conceived and marketed as a development for the elite. The David C. Bell Investment Company described its subdivision as home to “the class of progressive business and professional men who prefer to locate their homes among other homes of character and refinement…where the restrictions serve as a protection against undesirable neighbors.” The company issued a 1912 brochure that laid out the advantages for the whole family. “Your little ones will have healthy and well-bred children like themselves for companions.”

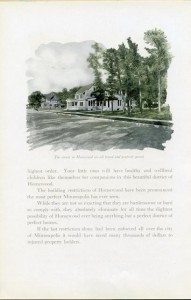

According to its developers, Homewood was “improved and restricted.” But its promoters drew boundaries along the lines of class, rather than race or religion. The subdivision’s covenants governed the type of residence that could be built, requiring buyers to construct houses costing no less than $3,000, located 35 feet from the front of the lot and three feet from the north side of each building site, with a foundation at least three feet above the sidewalk grade. There were consequences for violating the building restrictions. For example, a 1909 deed from Security Land and Investment to Nels Westerdahl stated if the covenants were broken then “this conveyance shall be void,” meaning the buyer would forfeit the property. The Homewood booklet indicated that no apartment buildings or retail stores would be built in Homewood, noting the restrictions “absolutely eliminate for all time the slightest possibility of Homewood ever being anything but a perfect district of perfect homes.” It promised that with strict application of building and zoning standards, the neighborhood would forever retain its economic value as a place of single-family residences.

This brochure advertising the Homewood development promised that “Your little ones will have healthy and wellbred children like themselves for companions in this beautiful district of Homewood.”

This material made it clear that there was no place for ordinary working families in Homewood. The message was unambiguously anti-democratic. But it’s not explicitly racist. This distinguishes this North Side neighborhood from similar developments in other parts of the Twin Cities. For instance, the Country Club District of Edina, which was built about the same time (1922), had the same property restrictions that governed Homewood. In addition, the developer attached the following caveat: “No lot shall ever be sold, conveyed, leased or rented to any person other than of the white Caucasian race, nor shall any lot ever be used or occupied by any person other than of the white Caucasian race except such as may be serving as domestics for the owner or tenant of said lot while said owner or tenant is residing there.”

Homewood developers might have assumed that these restrictions would keep out anyone who was not white or Christian. But this was not the case. Soon after it was platted and opened for development, Homewood filled with impressive homes built by Jewish families of comfortable means. The Weisbergs and the Bearmans were first. Benjamin M. Weisberg purchased land there in 1915––Lot 12 and part of Lot 13 in Block 10 of the Homewood Addition. That same year, Abraham N. Bearman purchased Lot 27 and part of Lot 28 in Block 7 of the Homewood Addition. These families were followed by many others, who created an enclave for upper-middle class Jews who were not welcome in other parts of the city.

This revelation raises as many questions as it settles. Why did Homewood–a neighborhood of Jewish families– become known as a place governed by racist real estate covenants? We know these types of covenants were used in Minneapolis–one estimate from the 1940s suggests that they covered one quarter of the properties in the city. But which neighborhoods used them? Have any of you found covenants in your deeds? If so, could you share?

The images are from a Homewood brochure held in the collections of the Hennepin History Museum.

Material for this post was taken from Ann Miller, “Homewood Has Unique History and Population,” Preservation Matters, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp.10-11; Judith A. Martin and David A. Lanegran, Where We Live: The Residential Districts of Minneapolis and Saint Paul (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983), 73; David C. Bell Investment Company, “Homewood Improved and Restricted;” Hennepin History Museum Collections. The story of racial/religious covenants also appears in Rhoda Lewin, Jewish Community of North Minneapolis (Arcadia Publishers, 2001), 46; and the Homewood Markers Project. Property records consulted include Hennepin County Torrens Certificate No. 3708, December 17, 1909; Hennepin Torrens Certificate No. 6713, March 29, 1915; Hennepin Torrens Certificate No. 12051, July 30, 1915. Examples of the Edina covenants are from the Country Club District, Fairway Section: Hennepin County Deeds Book 1235, page 261, November 21, 1930; Hennepin County Deeds Book 1240, page 617, recorded August 31, 1930; and Edina Country Club District, Wooddale Section: Hennepin County Deeds Book 1402, page 230, recorded January 22, 1937 and Hennepin County Deeds Book 1407, page 375, recorded April 9, 1937.