Guest blogger today is Jacqueline deVries, Professor of History and Women’s Studies at Augsburg College. deVries is writing a book on women’s health care in Britain and its empire.

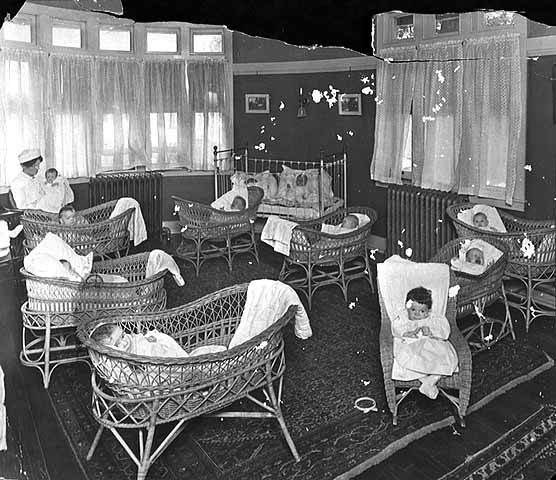

To modern eyes, there is nothing revolutionary about this sweet image of babies in nursery baskets. But these babies were wards of the Minneapolis Maternity Hospital, a radical institution that defied many social conventions of its time when it was founded by activist physician Dr. Martha G. Ripley in 1887.

Long before the Boston Women’s Health Collective published its path-breaking Our Bodies, Ourselves in 1971, Ripley was practicing feminist medicine. She established the Minneapolis Maternity Hospital for “the confinement of married women who are without mean or suitable abode and care at the time of child-birth” and “girls who have previously borne a good character, but who, under promise of marriage, have been led astray.” In other words, Ripley cared for the women on the margins of Minneapolis society, working to ensure safe and healthy childbirths for women who were largely ignored by the mainstream medical community.

Martha Ripley (1843-1912) moved to Minneapolis in 1883 after her husband was injured and lost his managerial job in a Massachusetts’ textile mill and she became the sole breadwinner for their three daughters.

Feminist politics and women’s medicine were Ripley’s twin passions. Shortly after her arrival in Minneapolis, Ripley was elected president of the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association, a new affiliate of the American Women Suffrage Association (AWSA) led by Ripley’s Massachusetts friends, Henry Blackwell and Lucy Stone. Drawing on her Boston connections, she brought the seventeenth annual convention of the AWSA to Minneapolis in 1885.

Ripley’s medical career had begun when she volunteered as a nurse in Lawrence, Massachusetts, providing palliative treatment to women textile workers and their families. After an infant died in her care, she vowed to gain more expertise. Inspired by Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman medical doctor in the United States and sister of family friend, Henry B. Blackwell, she enrolled at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM), one of the few medical schools in the United States that accepted women.

Popular attitudes toward professional medicine were not uniformly positive in the nineteenth century. Allopathic medicine – the drug-based treatment we now equate with medicine — competed with other theories of healing. Homeopathic medicine, an approach that emphasized the use of herbs, regular bathing, good ventilation, daily exercise, and a vegetarian diet, was taught by many of the nation’s medical schools, including BUSM. Homeopathy appealed to women as traditional healers — a third of Ripley’s graduating class were women.

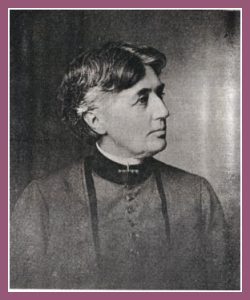

She brought a sense of activism to her medical work. Brushing aside Victorian conventions, she tackled “delicate subjects” like prostitution and the age of consent, set at ten years of age in 1858 when Minnesota became a state. She dismissed the popular belief that men needed sexual intercourse for health. And she braved criticism by providing medical services to unwed mothers. Her unfashionably short haircut (picture) signaled her independent attitude.

Recognizing a need for better maternity services in Minneapolis, she rented a small house on Fifteenth Street and hired a nurse in 1886. Within a year, the Maternity Hospital was incorporated as a homeopathic lying-in hospital. By 1896, the hospital moved to a five-acre tract at the corner of Western and Penn Avenue North, pictured here.

The Maternity Hospital’s track record was remarkably successful. Dr. Ripley insisted on aseptic practices and a cottage system (picture) in which babies were cared for in domestic settings. Not one child was lost during actual birth in the first eleven years, and for the decade ending in 1937 the maternal death rate was 1.35 per thousand as compared to a state-wide average of 4.5.

A new building for the Maternity Hospital was constructed shortly after Ripley’s death in 1912. This building still stands at 2215 Western Avenue, though the hospital was shuttered in 1956. A bronze memorial plaque in her honor was dedicated in the State Capitol rotunda in 1939.

Notes: Material for this post is taken from Thomas Neville Bonner, To the Ends of the Earth: Women’s Search for Education in Medicine (Harvard, 1992), Mary Wittenbreer, A Woman’s Woman / A Woman’s Physician: The Life and Career of Dr. Martha G. Ripley (M.A. Thesis, Hamline University, 1999), and Winton U. Solberg, “Martha G. Ripley: Pioneer Doctor and Social Reformer,” Minnesota History 39:1 (Spring 1964): 1-17.

The photo of Martha Ripley is from the Minneapolis photo collection at Hennepin County Special Collections. The photos of the Minneapolis Maternity Hospital are from the collections of the Minnesota Historical Society.

One thought on ““The Duty of Not Keeping Silent”: Martha Ripley and Minneapolis Maternity Hospital”

Comments are closed.