The Pioneer Hotel: Welcome to your cage

Today’s guest blogger is James Eli Shiffer, author of the newly published book, The King of Skid Row: John Bacich and the Twilight Years of Old Minneapolis. This Thursday at the Mill City Museum, James will be talking about his book at the opening of a new exhibit that features previously unpublished images of the city’s lost Gateway District.

In the pantheon of vanished Minneapolis accommodations, the Pioneer Hotel ranks exceedingly low. In fact, there probably aren’t many people around who even remember the place, which was swept away with other low-end hotels during the Gateway urban renewal project of the early 1960s. The Pioneer had the distinction of being photographed extensively by the city Housing and Redevelopment Authority in 1960, shortly before its destruction, making it perhaps the best-documented flophouse in Minneapolis history.

The Pioneer occupied the upper floors of an old commercial building at the corner of Nicollet Avenue and 2nd Street South, in the heart of the old Skid Row. It was a cage hotel, also called a cubicle hotel, meaning that its tiny rooms were constructed of plywood and tin dividers, with chicken wire over the top. The residents of the Pioneer, single, aging men who were primarily retired railroad or other seasonal workers, shared bathrooms and found companionship playing cards or just letting their bellies hang out in the day room.

Cage hotels emerged in Minneapolis in the late 19th century, as a way to house the migrant laborers who came to the city to find work and then to stay while they spent their earnings from the railroads, the farms and the logging camps. By 1895, there were 50 cage hotels in Minneapolis. While these hotels provided a cheap place to stay, the rest of Minneapolis found them increasingly distasteful. The city outlawed new cage hotels in 1918, but they were such an established institution that some of them lasted for four more decades.

The Pioneer Hotel was owned by Charlie Arnold, whose own accommodations reportedly included a mansion in southern California. He told a reporter from the Minneapolis Star in 1958 that he owned four Skid Row hotels, and said he provided a home to “many fine old gentlemen.” One of those guests, Adolph Karlsson, said he was amenable to moving out of the way of the impending redevelopment “if we can have another place where men like myself can stay and have companionship. When a man reaches middle age and he can’t get a steady job, he needs a place where he can get a cheap room and cheap meals,” The Star’s photographer, Larry Schreiber, snapped a photo of three residents of the Pioneer playing cards in the dayroom.

William Bridges, Gust Tarsuk and Clifford Christjohn playing cards at the Pioneer Hotel. Minneapolis Star Tribune photograph. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

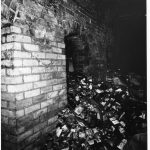

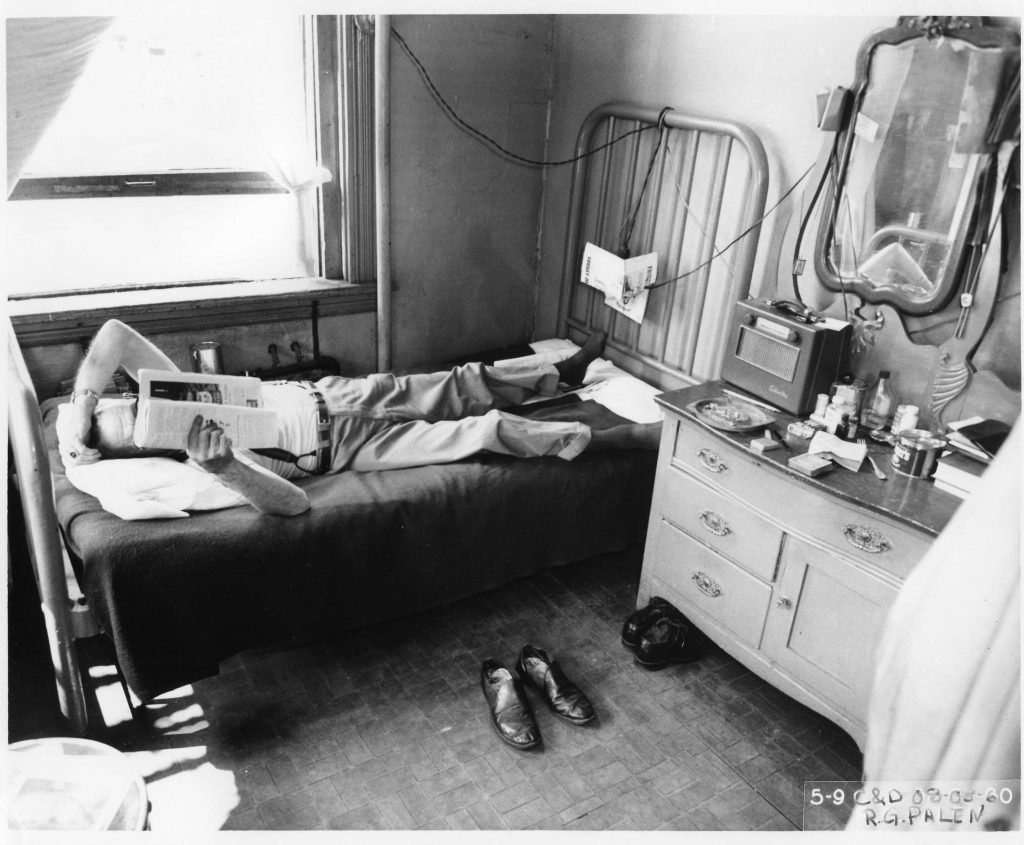

Two years after the Star’s story, Richard Palen, a photographer commissioned by the city, visited the Pioneer to document the condition of the building and its interiors. The men he found lounging in the day room or reading on their beds were merely bystanders as the city documented its “blight.” The bathrooms were dismal, the basement was heaped with liquor bottles and the whole place looked like a firetrap. But for generations of seasonal laborers, pensioners and others who helped build Minneapolis and the upper Midwest, the Pioneer was home.

Photographs by the city of Minneapolis Housing and Redevelopment Authority, ca. 1960. From the Special Collections, Minneapolis Central Library, Hennepin County Library.