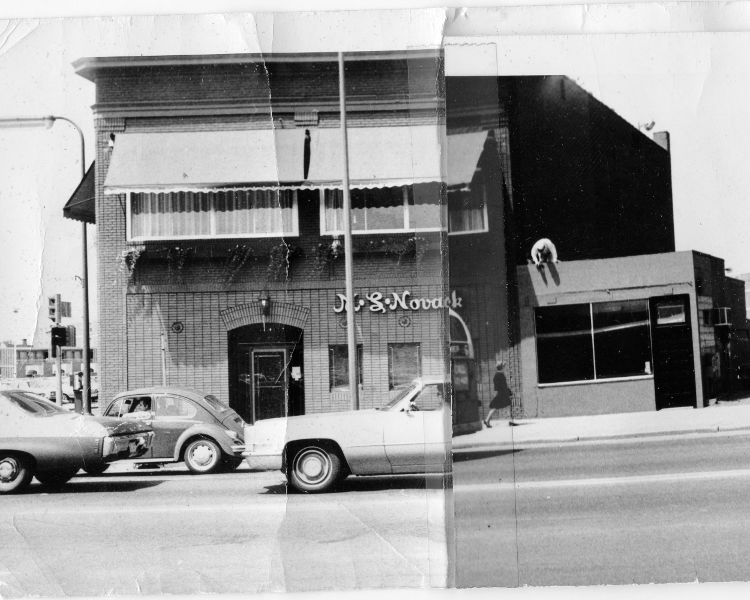

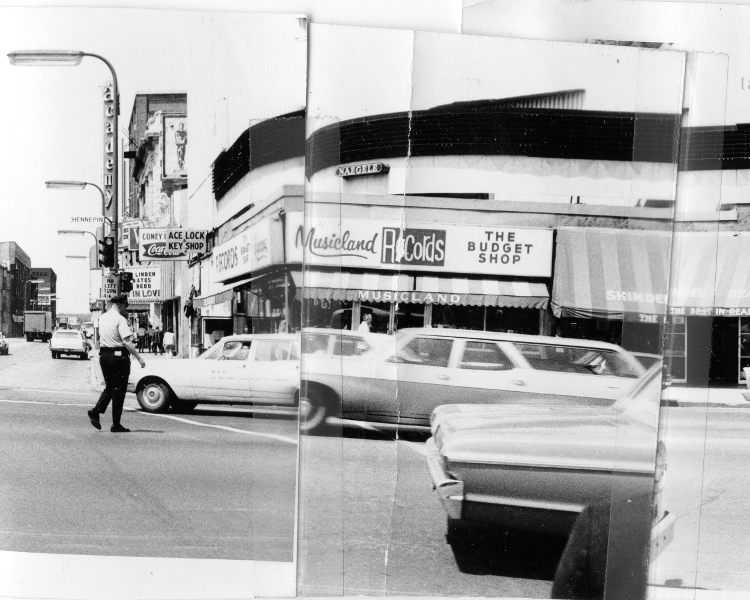

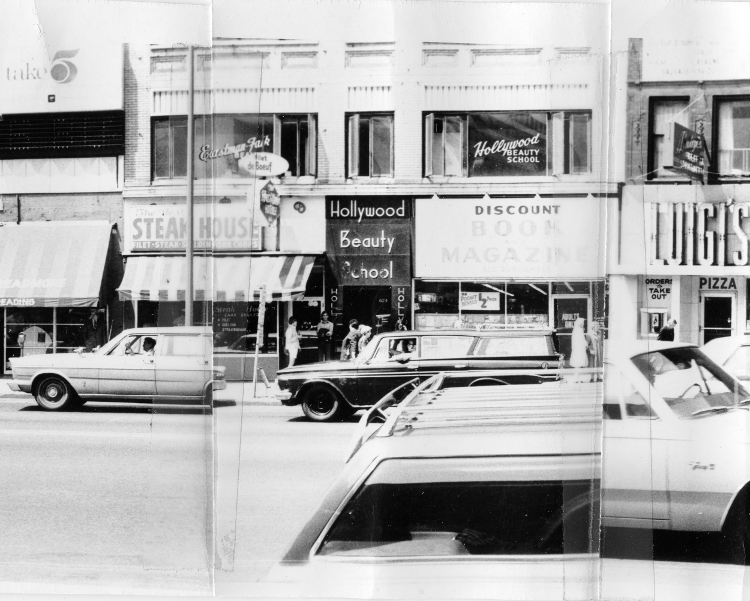

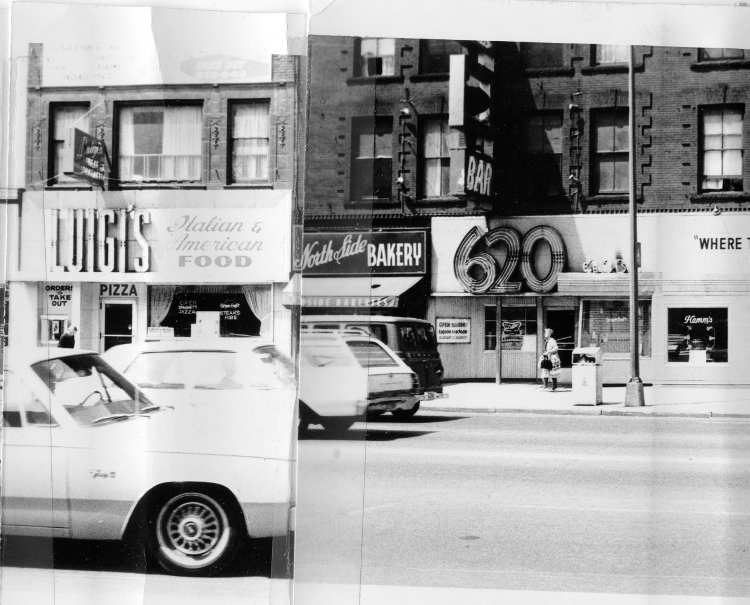

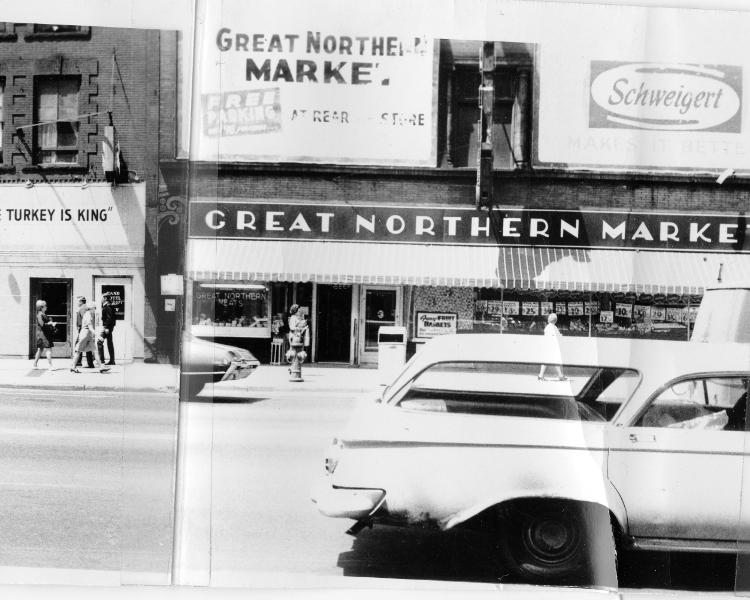

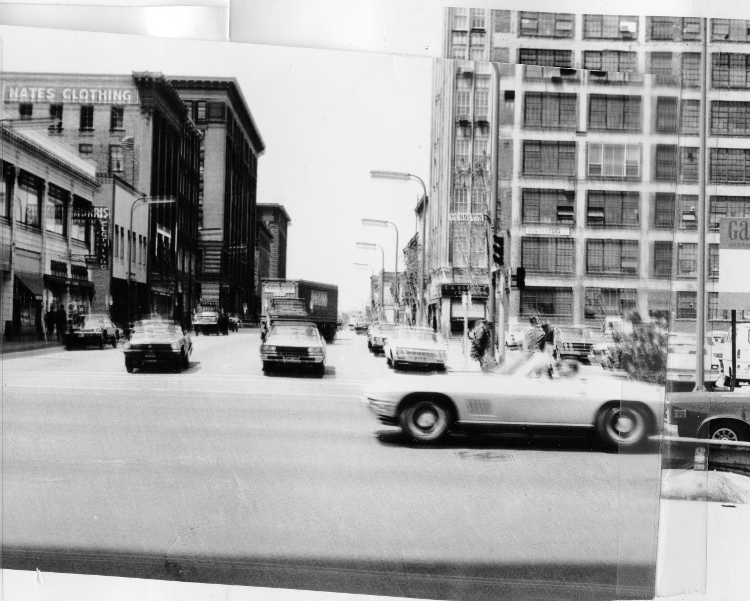

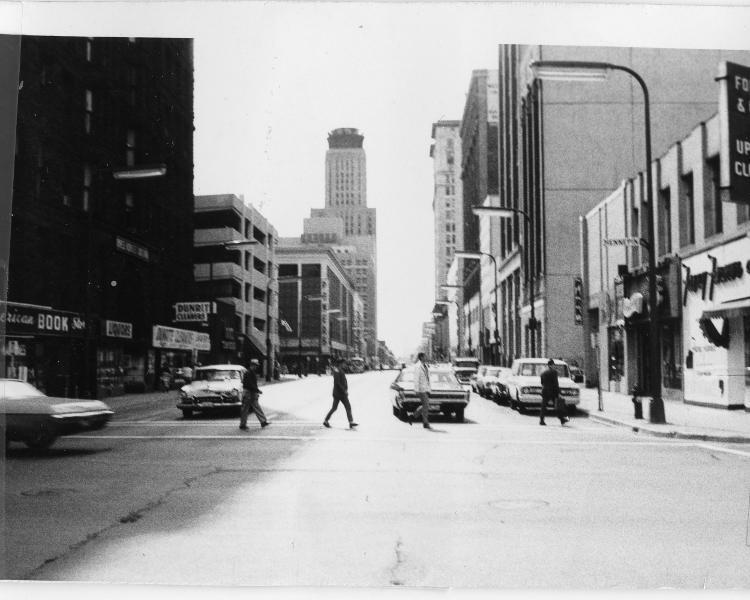

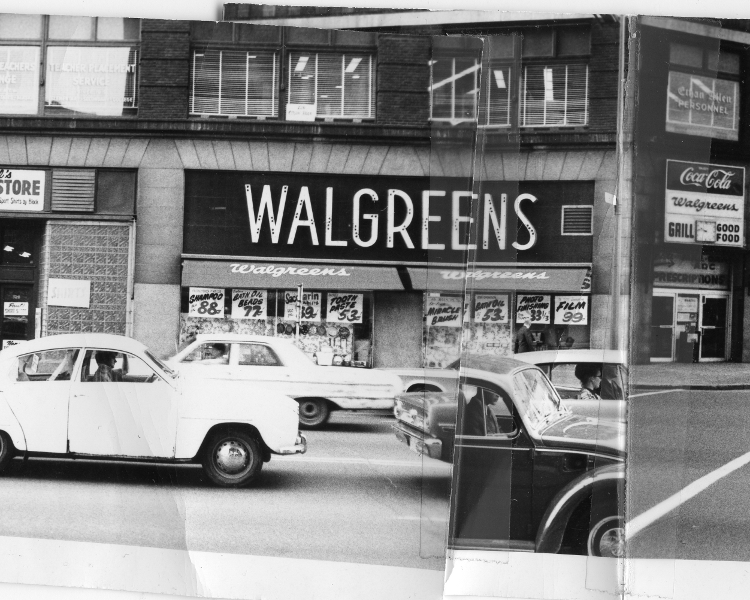

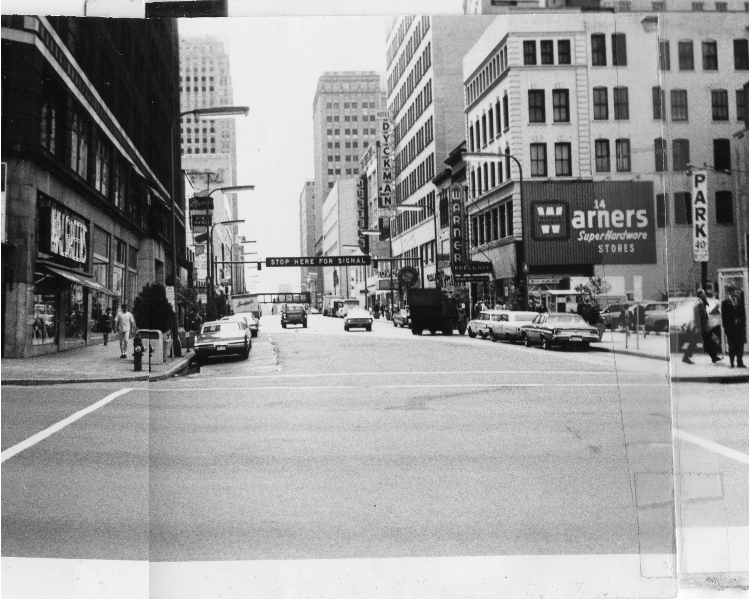

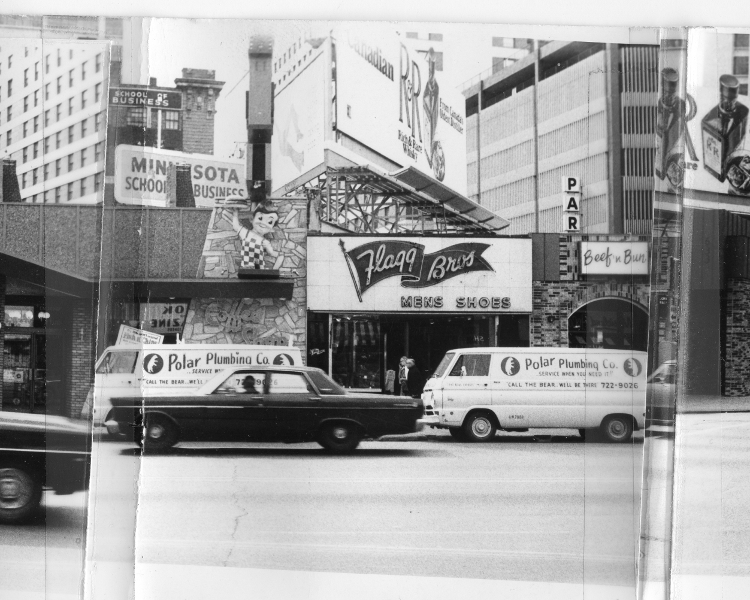

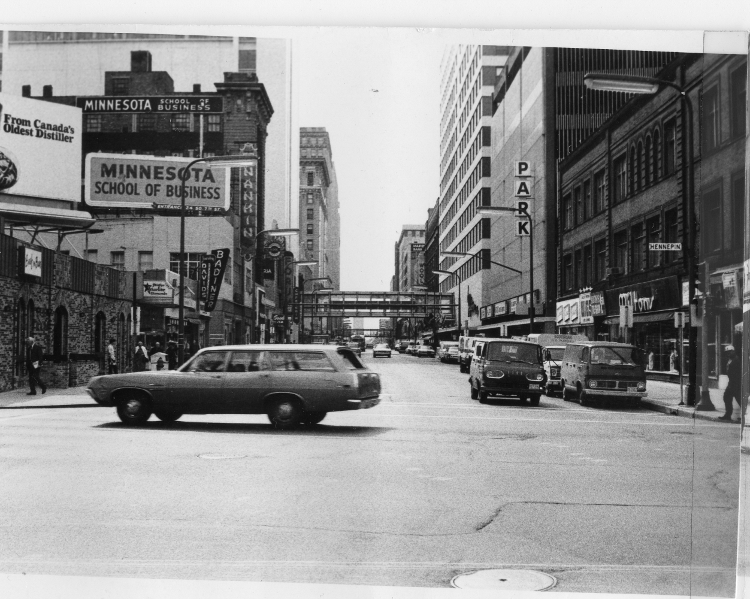

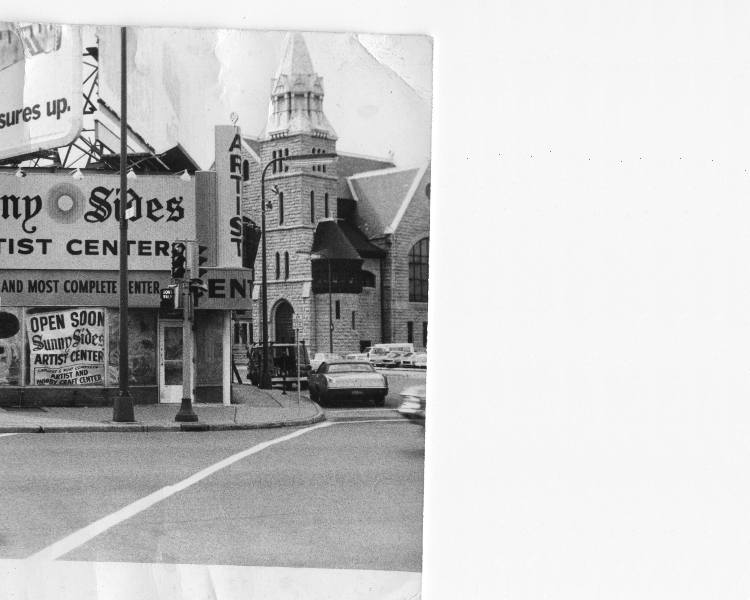

In the early summer of 1970, an employee of Minneapolis city government did a photographic survey of Hennepin Avenue downtown. The goal was to document six blocks of the city’s most famous avenue, on the border of the newly demolished skid row, where its “bawdy charm” was most pronounced. Developed as a main artery for the nineteenth-century city, Hennepin Avenue was one of the oldest commercial strips in Minneapolis, linking the Mississippi River to the southwestern chain of lakes.

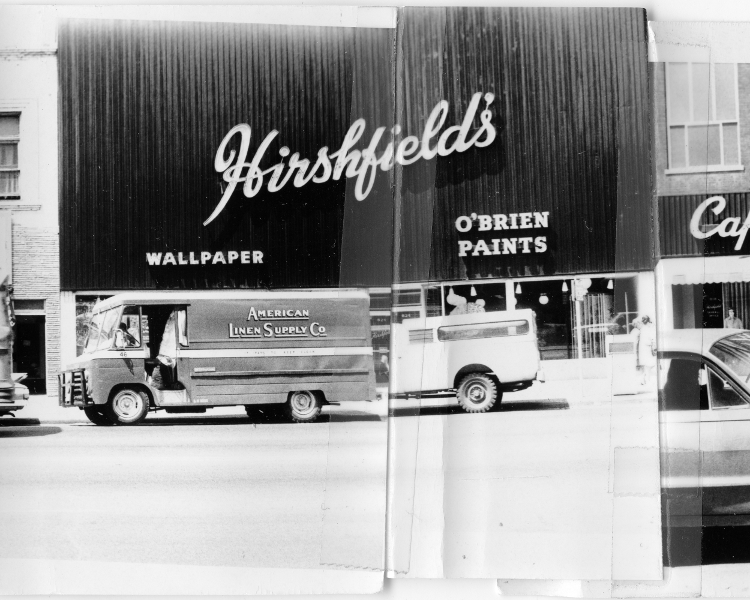

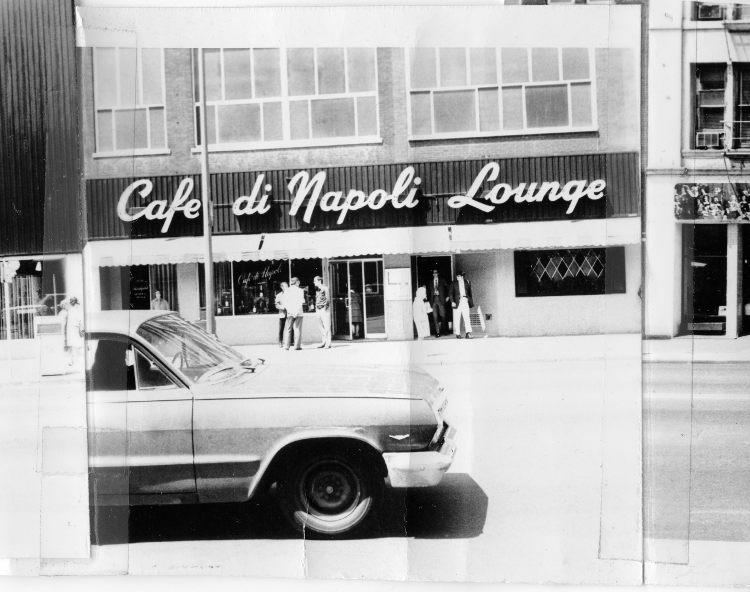

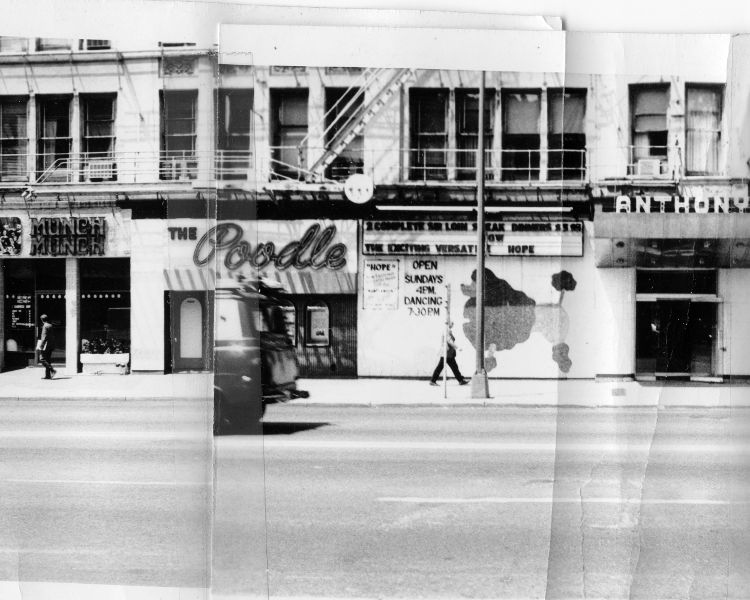

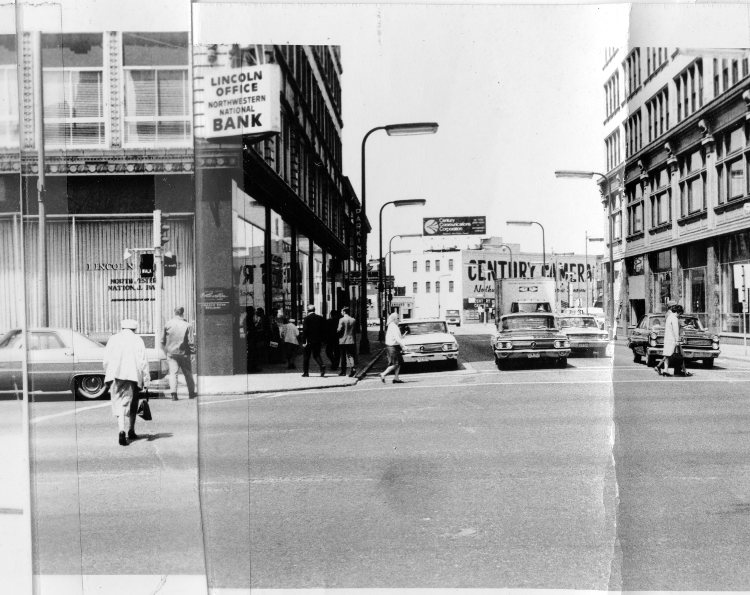

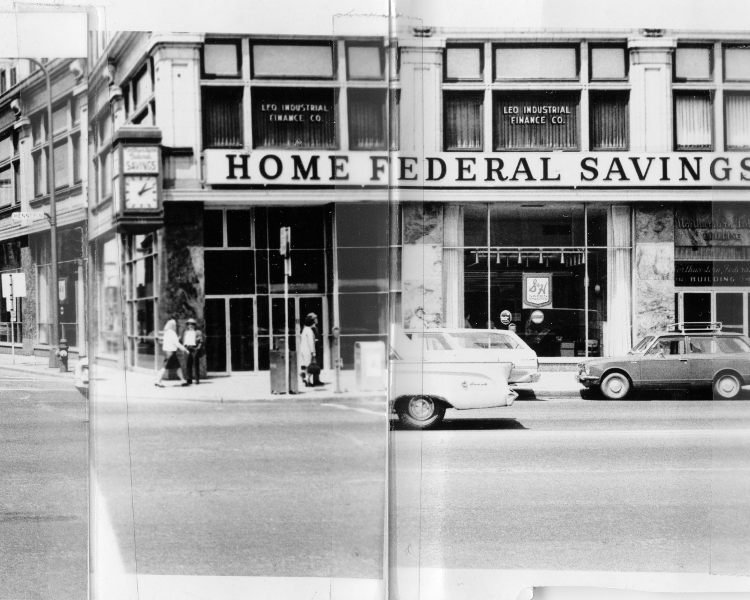

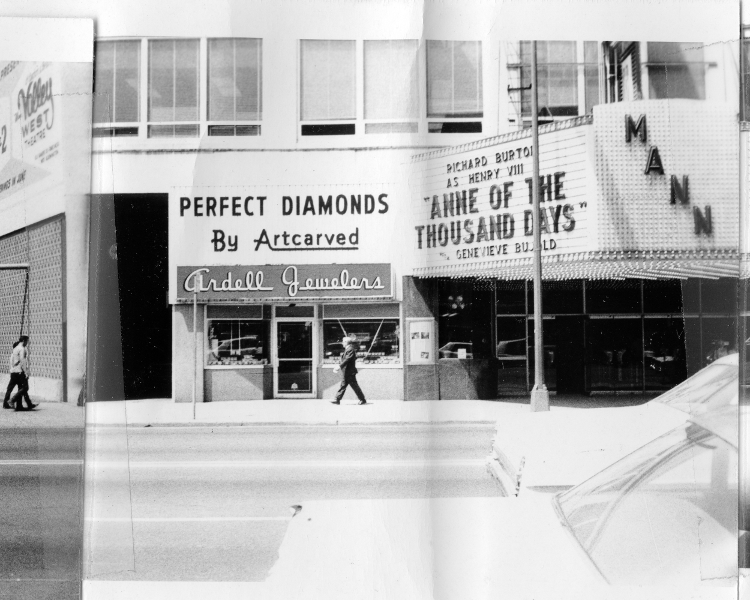

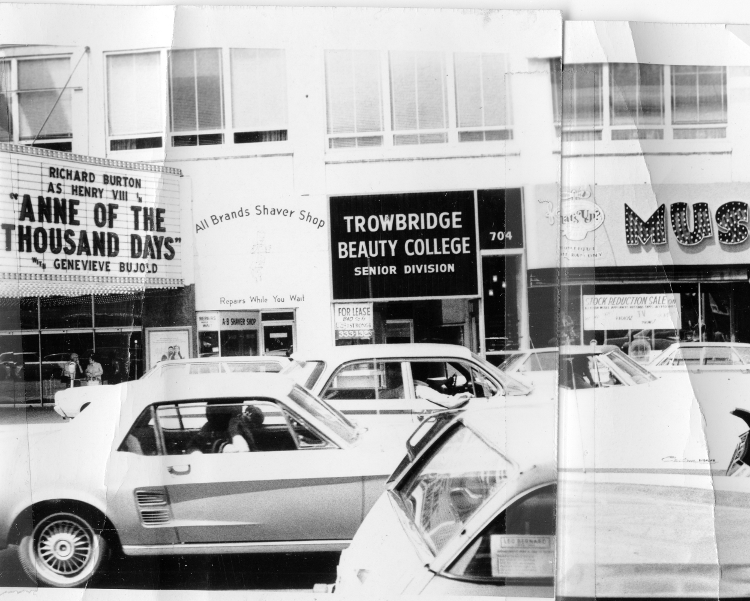

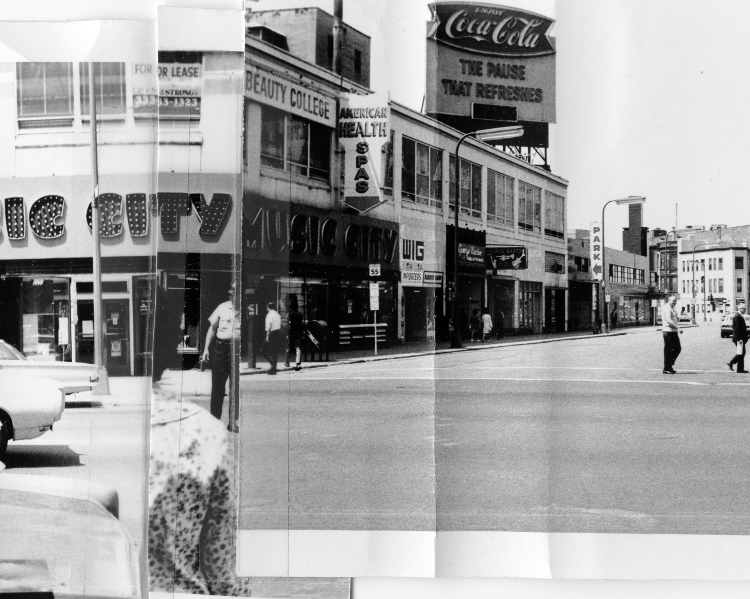

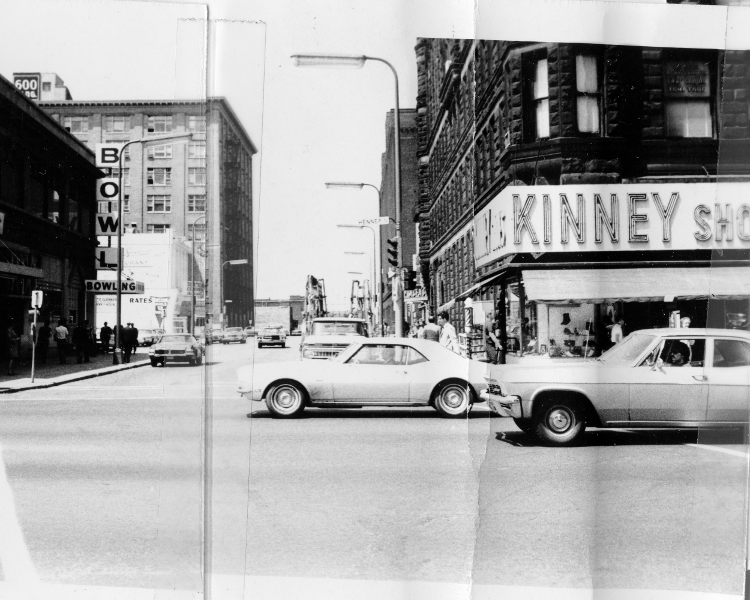

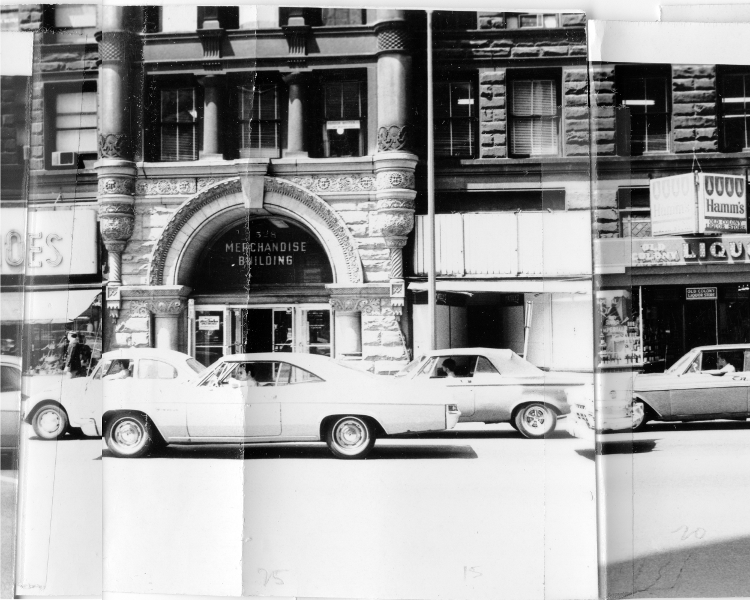

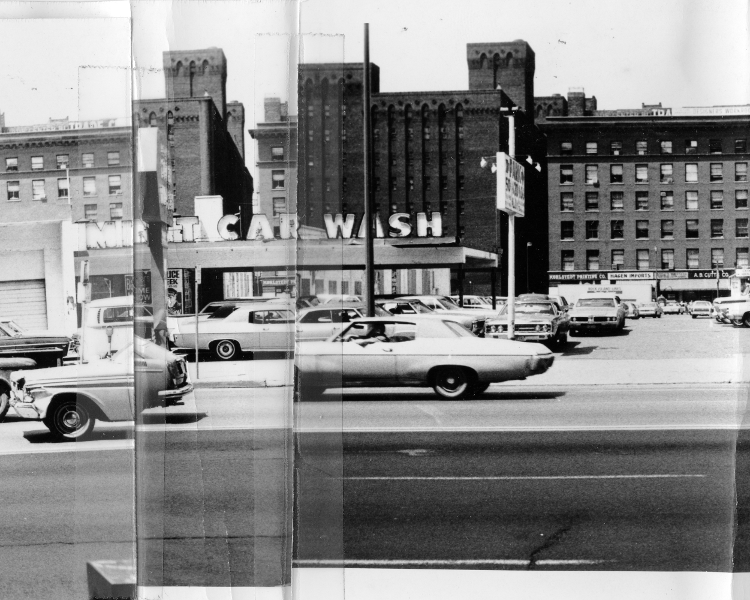

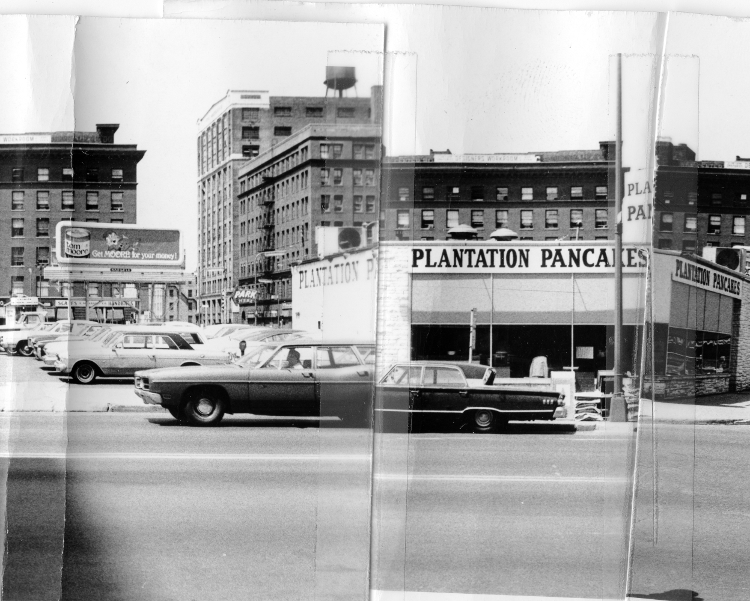

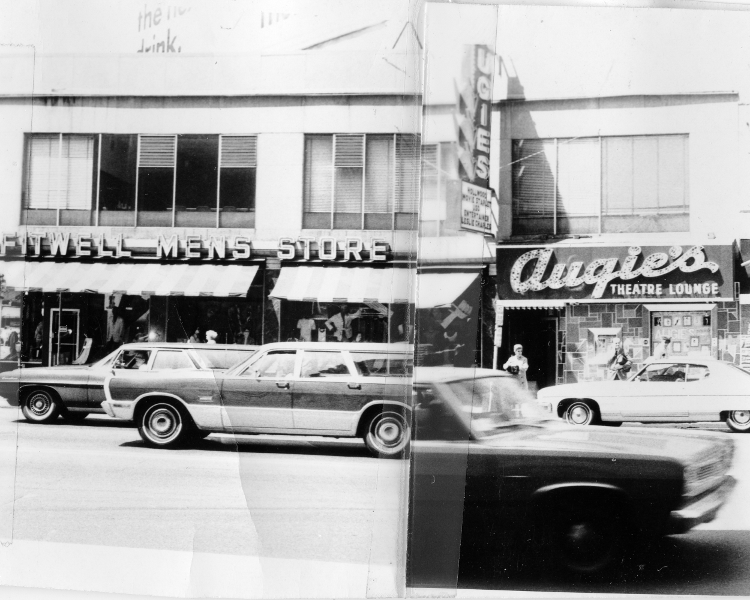

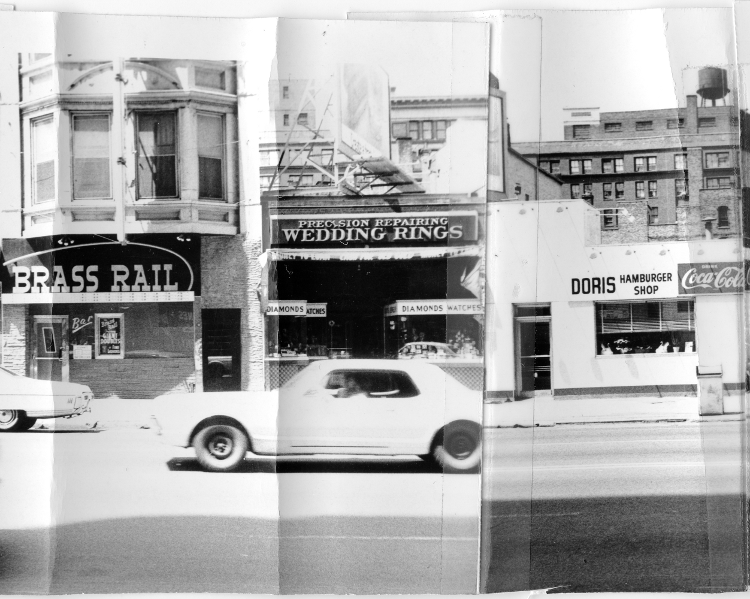

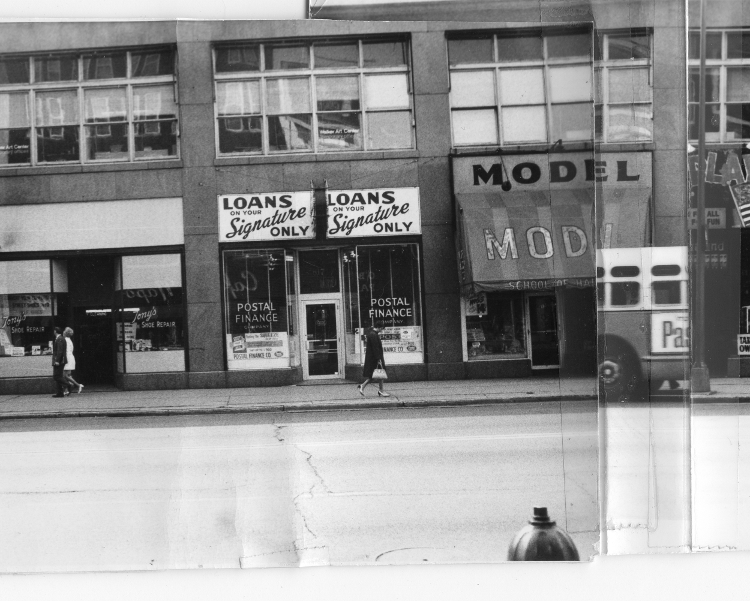

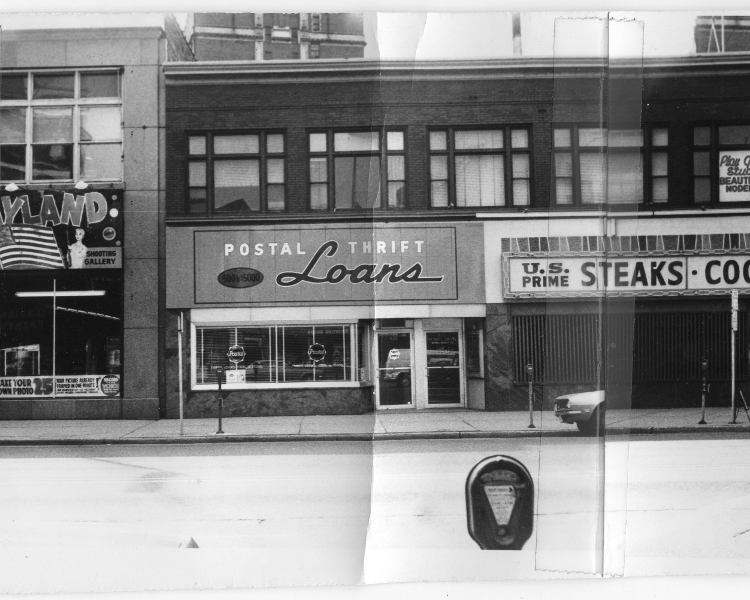

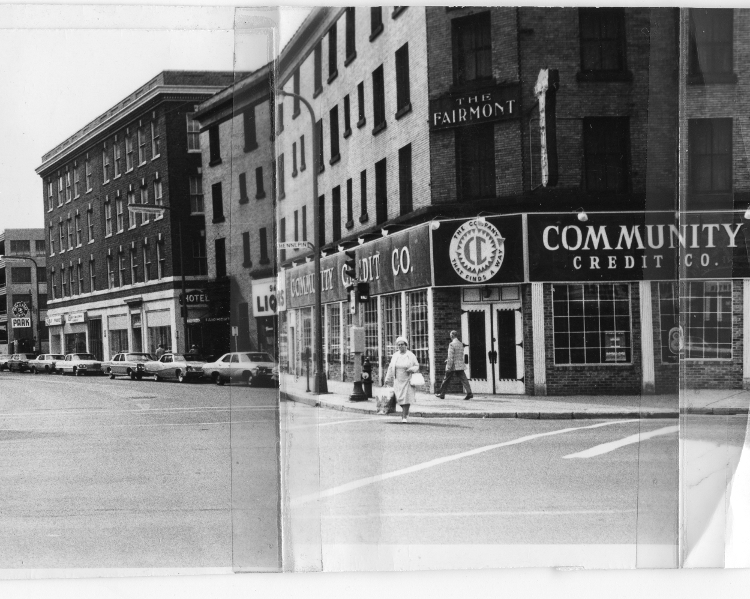

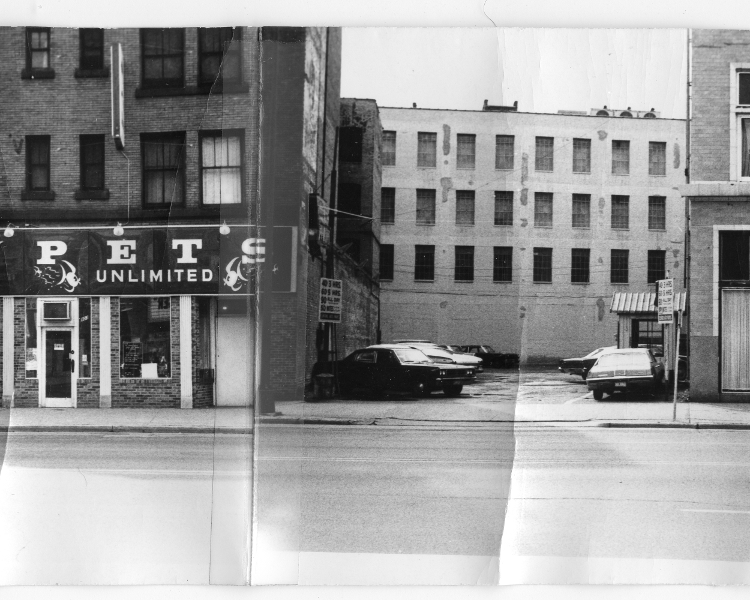

The photographer walked the east and the west side of the street, taking a series of black and white snapshots in quick succession. The images were developed, printed and then taped into two crude panoramas, each stretching four feet in length. One strip shows the east side of the street; the other shows the west. After Historyapolis citizen-researcher Dan Wilhemsen stumbled on these curled-up panoramas in the tower archives at City Hall, we decided we wanted to share them with all of you.

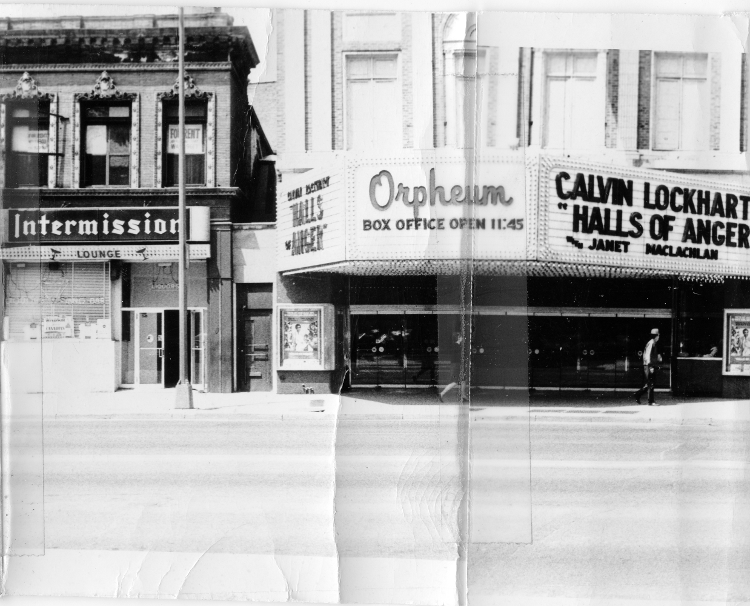

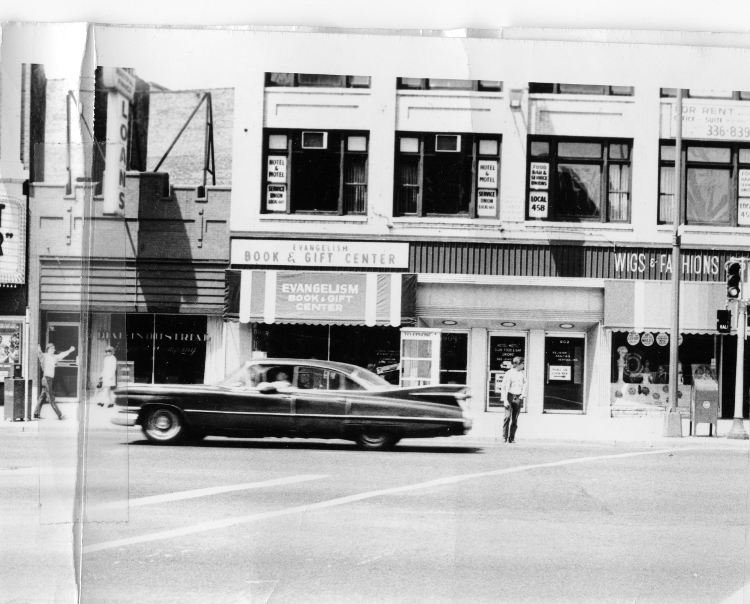

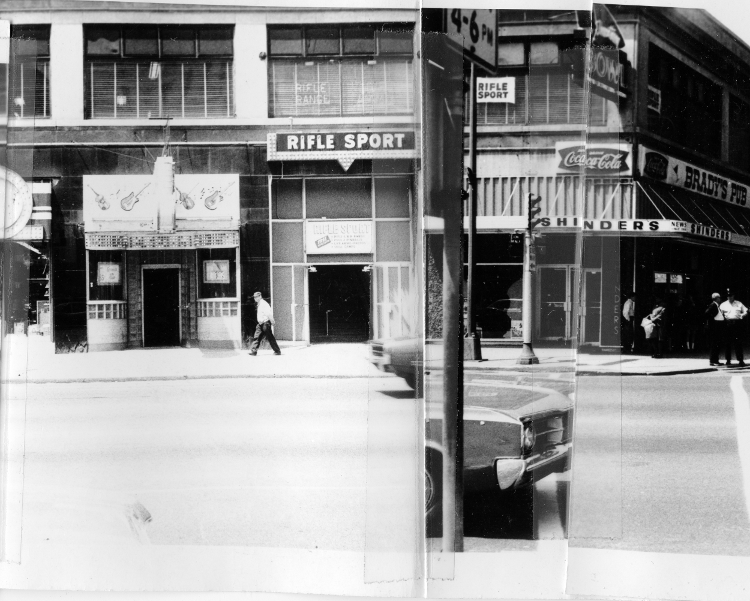

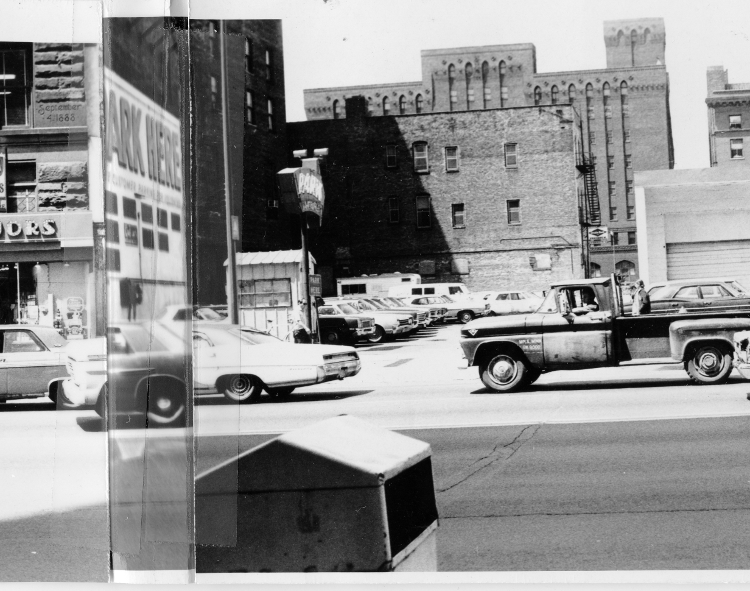

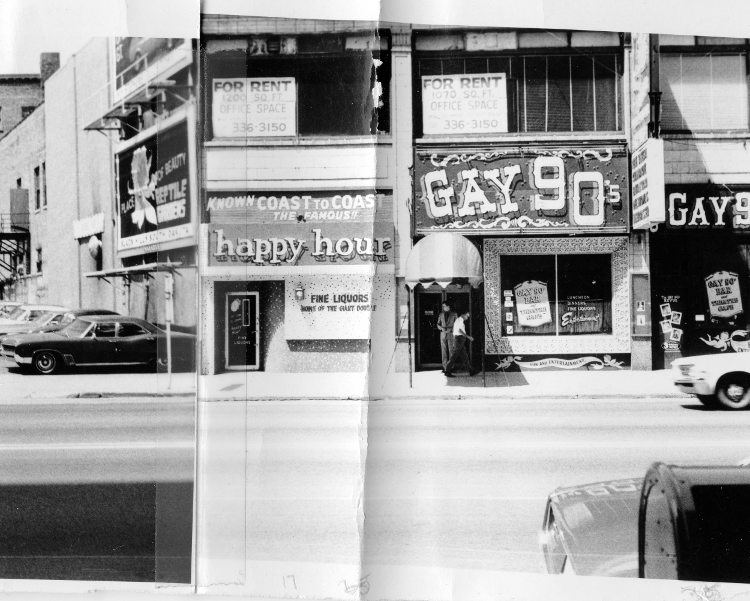

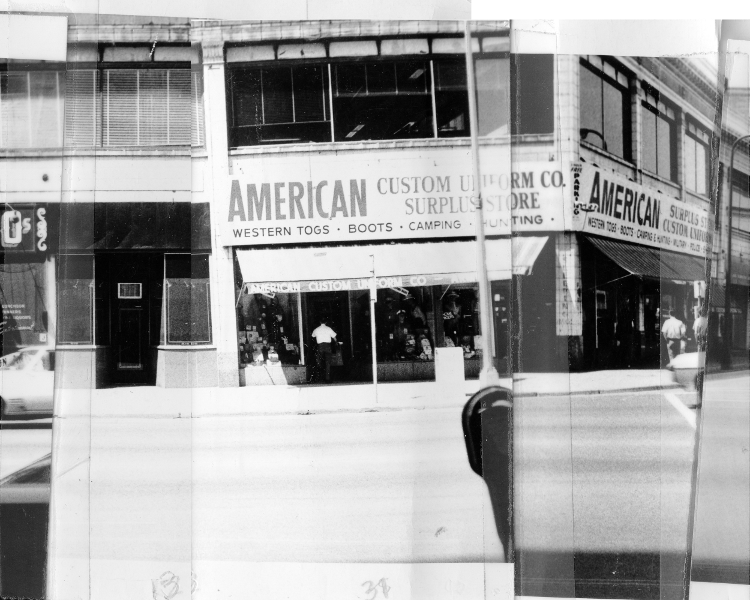

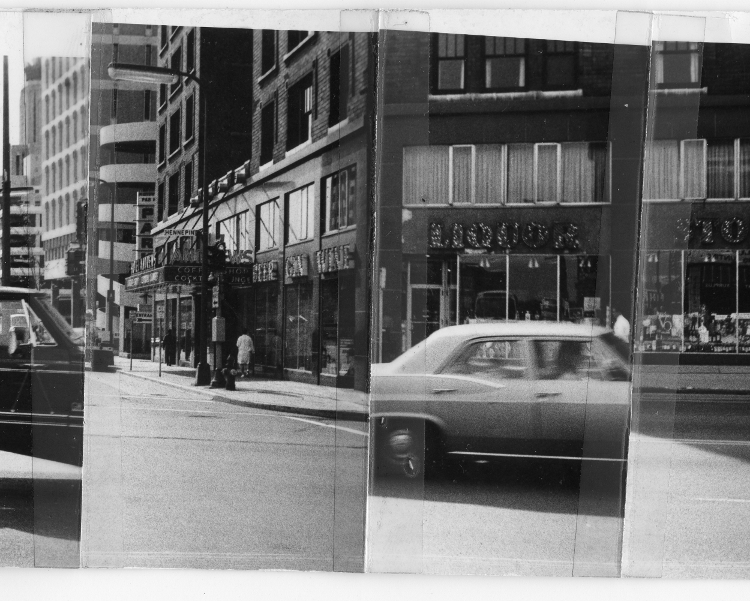

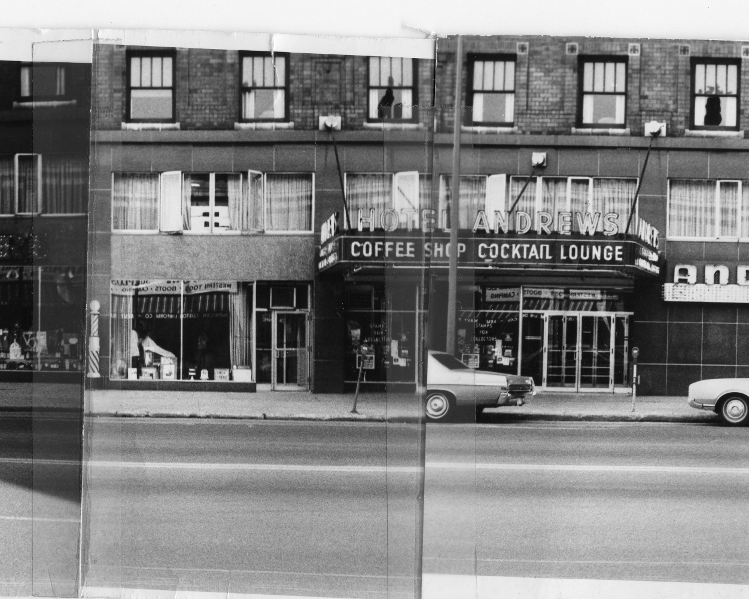

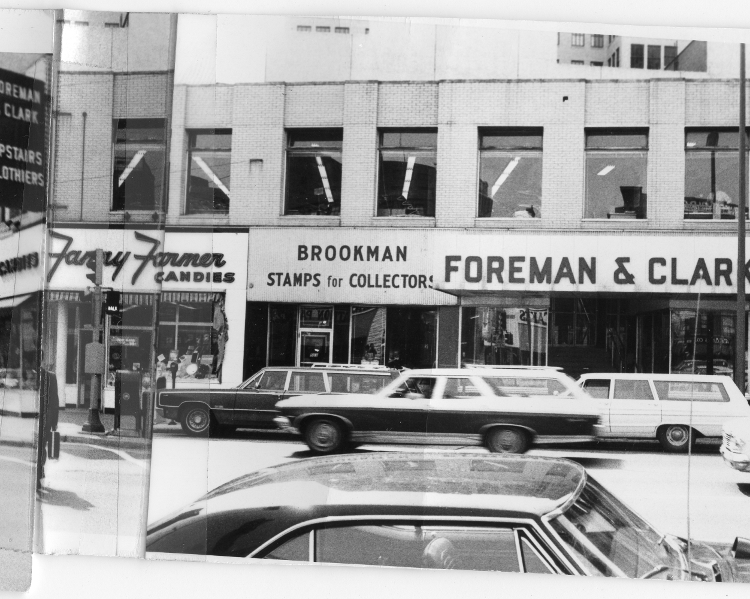

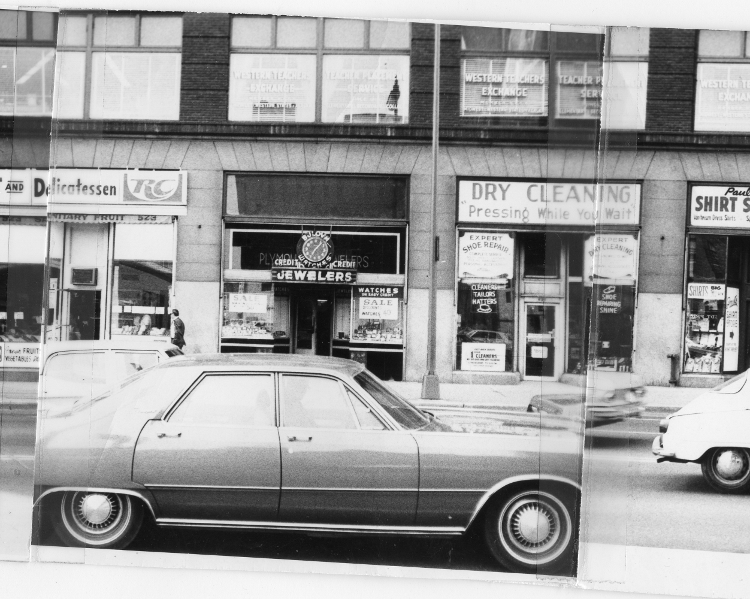

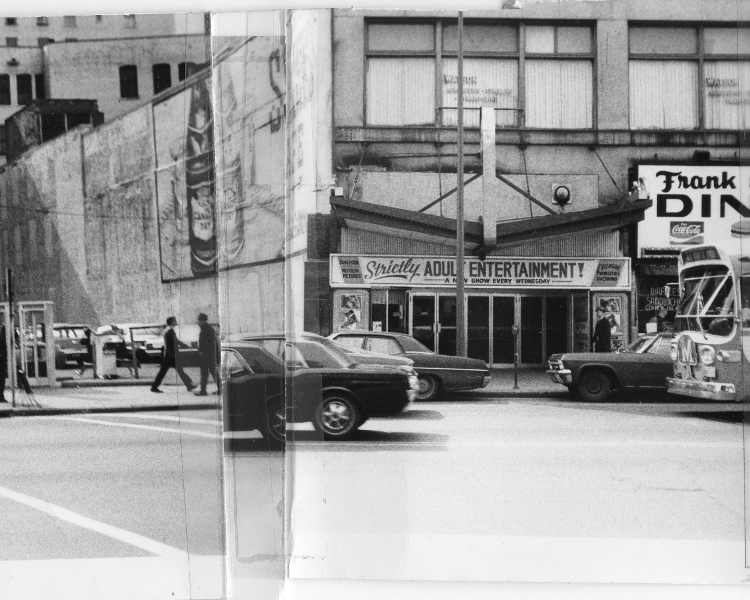

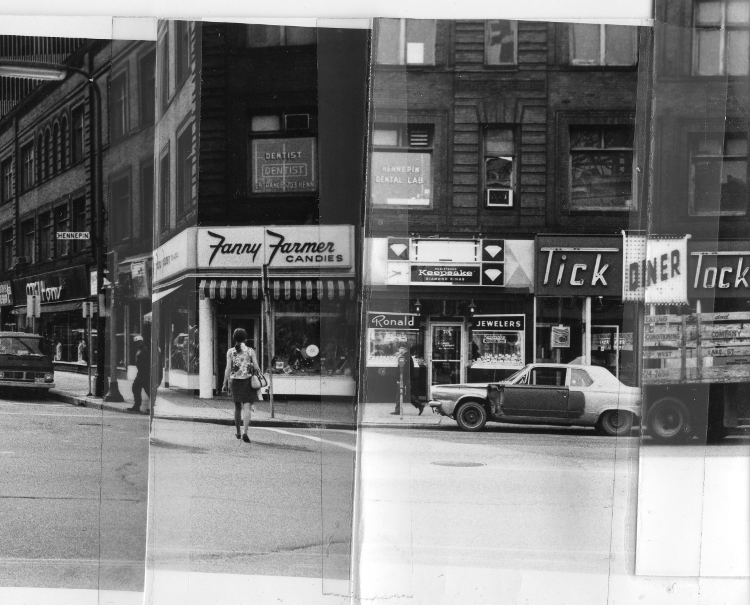

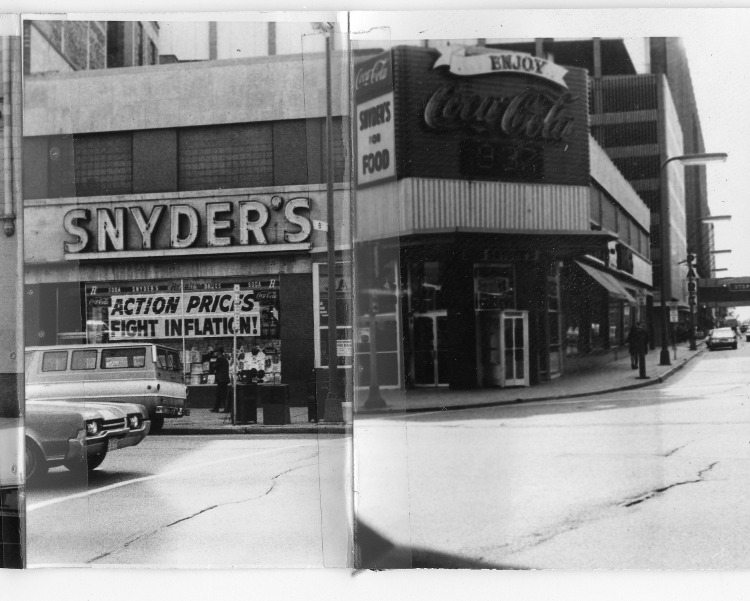

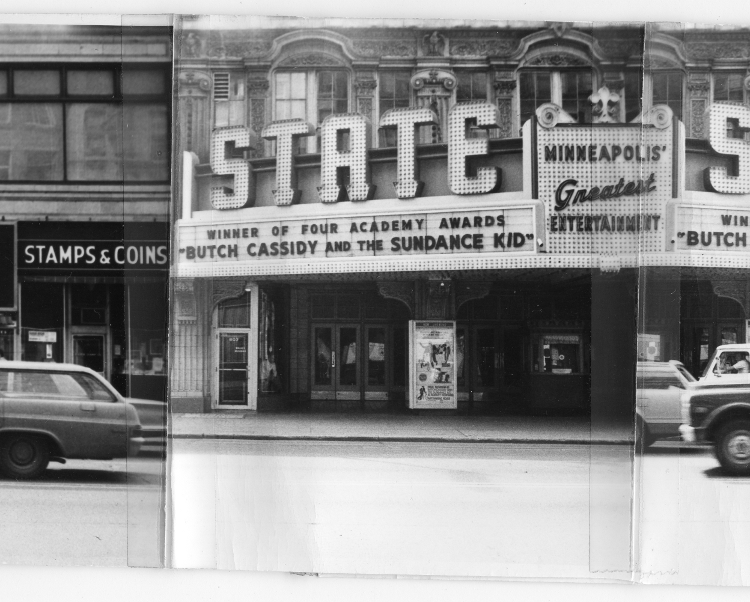

Click on the slider created by Historyapolis intern Kevin Ehrman-Solberg to see a host of legendary Minneapolis establishments and the surrounding streetscape. This stretch of “the avenue”–as it was called–included the Hotel Andrews; Augie’s Theatre Lounge; the Brass Rail; Rifle Sport; Shinders Bookstore; the Poodle Club; the Saddle Bar; the 620 bar “Where Turkey is King”; Plantation Pancakes; Music City and Musicland; the Hi-Lo 29 Bar; and the Gay ’90s. Catch a glimpse of the Cafe di Napoli, described by Minneapolis booster and columnist Barbara Flanagan as “a Hennepin Avenue landmark and one of the few good restaurants left on that street worth visiting. ”

The photographs are not annotated. But the movie marquees helped us to fix the approximate date they were taken. The Orpheum Theater–a first run cinema at this point –was advertising “Halls of Anger,” which was released on April 29th, 1970. “A Man Called Horse,” which came out on the same day, played at another venue down the block.

Thanks to Google streetview and the increasing fascination with urban “street” art photography, these types of images seems utterly familiar to modern viewers. But there is nothing high-tech or artsy about this project, which was supposed to provide an utilitarian and unvarnished portrait of the city’s grittiest blocks for urban planners and community leaders.

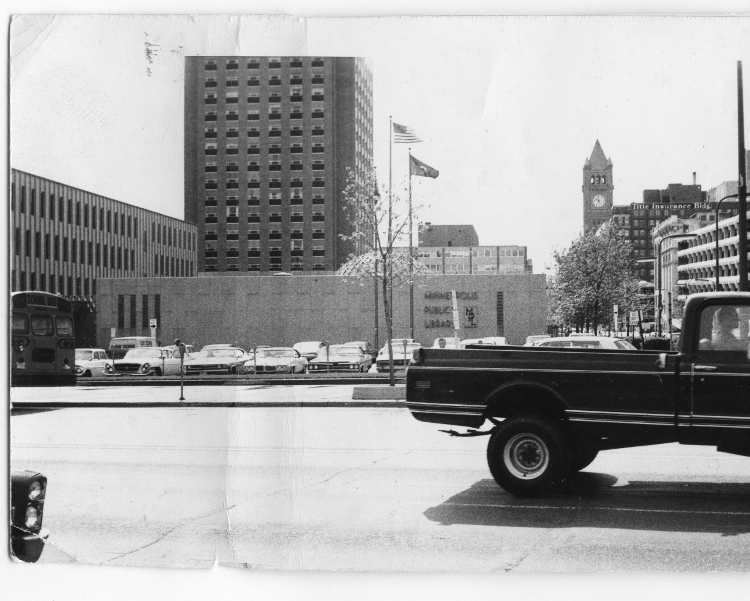

When this panorama was created, this stretch of Hennepin Avenue was viewed as a hard-to-ignore blemish on the face of an otherwise model metropolis. In 1966, the Minneapolis Star called it “a street with a personality problem, beckoning only the more adventuresome to its strip joints, paperback bookstores and streetwalking businesswomen and their agents.” It was encircled by ambitious urban renewal projects, bordering the massive Gateway Center district that sacrificed 40 percent of the downtown in an effort to eradicate the region’s largest skid row. The plan was to replace this nineteenth century streetscape of bars and cage hotels with a futuristic district of skyscrapers. The historic buildings came down. But of course this Minneapolis Futurama never went up.

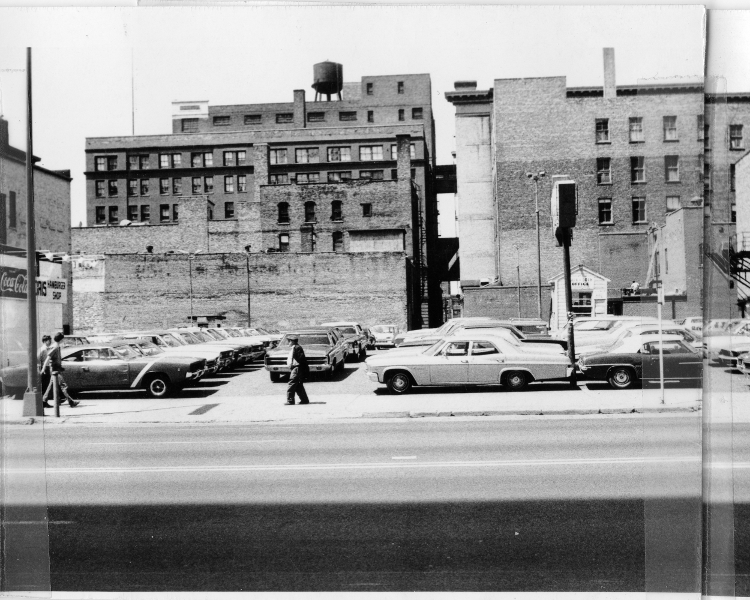

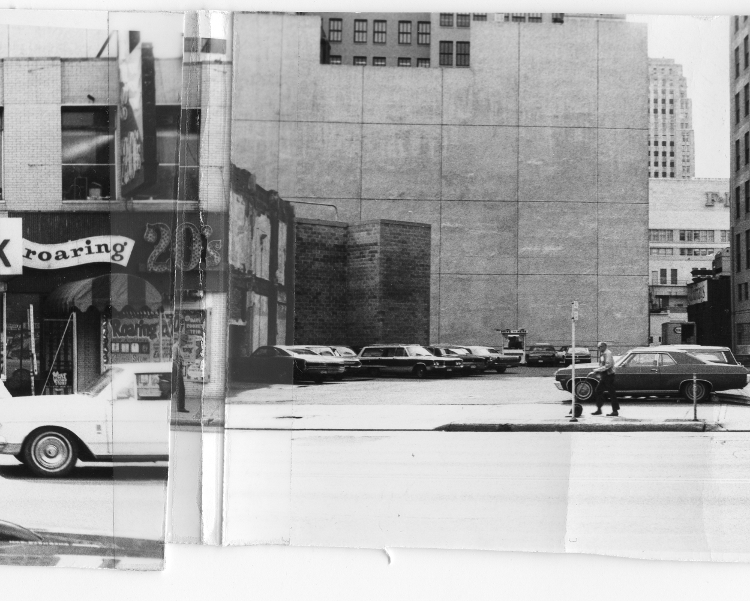

These images show how the reality of the avenue contrasts with the dazzling vision of city planners. More than a decade after the Gateway redevelopment was supposed to catalyze the creation of a modern city, this panorama reveals how the street was honeycombed with empty lots that generated modest income as surface parking lots. A billboard touting the coming Gateway Center–more than a decade after demolition began–towers over a sea of parked cars.

The increasingly visible role o the commercial sex industry is also obvious. Liberalizing obscenity laws helped to fuel the expansion of adult entertainment establishments in the late 1960s. From this node on Hennepin Avenue they would spread throughout the city, becoming a source of intense community contention that culminated in an ordinance banning pornography in 1983. In these images, shadowy figures loiter outside of anonymous storefronts advertising “Books,” “Magazines ” and “Strictly Adult Entertainment.”

In 1968, the city’s shopping street–Nicollet–had been redeveloped as a pedestrian mall that captured the attention of urban planners around the world. This project was widely imitated and lauded as a new model for American downtowns. The Mall became a mecca for graduate students, foundation researchers and magazine writers who wanted to understand why the city was flourishing while the rest of the country was mired in what was known as the “urban crisis.”

This stretch of Hennepin Avenue was seen as the antithesis of its sister street. “If the Avenues of downtown Minneapolis were personalized, Hennepin would probably be the disheveled and somewhat uninhibited spouse of the well-dressed and proper Nicollet Mall,” a report to the mayor declared. “They are an inseparable pair, going everywhere together, even though the degree of Hennepin’s drinking problem and its deportment and appearance does affect the image of the entire family.”

The success of the Nicollet Mall fanned enthusiasm for large scale urban renewal projects, making the deficiencies of Hennepin Avenue intolerable to city boosters. One year after the completion of Nicollet Mall, they commissioned its designers–Lawrence Halprin & Associates–to create a plan for improvement. But when these plans remained on the drawing board, the Walker Art Center–in cooperation with the Minneapolis Downtown Council and the city Planning Department–organized a symposium that invited artists, architects, designers and urban studies specialists to pitch ideas for revitalizing the avenue. These sessions were held on April 25 -26, 1970 and likely inspired the making of this panorama.

This same event probably also spurred the Minneapolis Tribune writer Allan Holbert to write a piece he called the “Dirty Old Man’s Guide to City,” a tongue-in-cheek description of Hennepin Avenue published during the symposium. Holbert urges readers to visit one of the “friendly bookseller’s shops” on the avenue, since “you’ll probably want to pick out some gifts for the folks back home.” These stores, he explained, offered a selection “ranging from battery-run personal vibrators…to such illustrated magazines as ‘Linda and Laurie,’ ‘Erotic’ and ‘Fun and Games.'” Visitors could also enjoy the show at the Roaring 20s, he explained, where topless dancers gyrated to some of “the best jazz that can be heard in the Twin Cities.”

As the 1970s unfolded, Minneapolis might have been too busy enjoying its status as an urban paragon to take on the difficult and expensive work of redeveloping Hennepin. City leaders could take solace in the fact that at the depths of the urban crisis, Minneapolis seemed to be defying gravity. While other cities burned, Minneapolis glowed with life.

Moreover, as the Gateway Center redevelopment seemed to lose its momentum and neighborhood activists in Cedar-Riverside organized to halt the wholesale demolition of their neighborhood, critics of urban redevelopment were also gaining visibility. They urged Minneapolitans to embrace “Hennepin’s unpredictability and unconventional behavior” as “interesting and refreshing.” In 1982, it was these very qualities that inspired local artist Patrick Scully to make a quirky film about this stretch of downtown that he called “Shinders to Shinders.” Scully took the same gritty scene and used it as the backdrop for conceptual dance and music pieces that celebrated this stretch of Hennepin as the epicenter of the funky, new-wave urbanity of the 1980s.

It was not until the 1990s that the “avenue” was subjected to a comprehensive redevelopment plan, which changed the streetscape but not the gritty and bawdy character of the city’s entertainment district.

Sources for this post include Allan Holbert, “Dirty Old Man’s Guide to the City,” Minneapolis Tribune, April 26, 1970; The Report to the Mayor: Hennepin Avenue: Assumptions, Choices, Recommendations, April, 1979, Hennepin History Museum; “How Minneapolis Fends Off the Urban Crisis,” Fortune Magazine, January, 1976; Barbara Flanagan, Minneapolis: City of Lakes and Skyways (Minneapolis: Nodin Press, 1973); “Hennepin: The Future of an Avenue,” Design Quarterly, No. 78/79, 1970: 59-63; Joanna Baymiller, “History of an Avenue,” Design Quarterly, No. 117, Hennepin Avenue (1982): 6-11; Rob Nelson, “Where Were you in ’82?” City Pages, Feburary 6, 2002.

2 thoughts on “Summer in the City: Hennepin Avenue, 1970”

Comments are closed.