Lost neighborhoods and forgotten archives

It’s map Monday. Today we have a map from the Minneapolis City Archives, a little known repository of our community history.

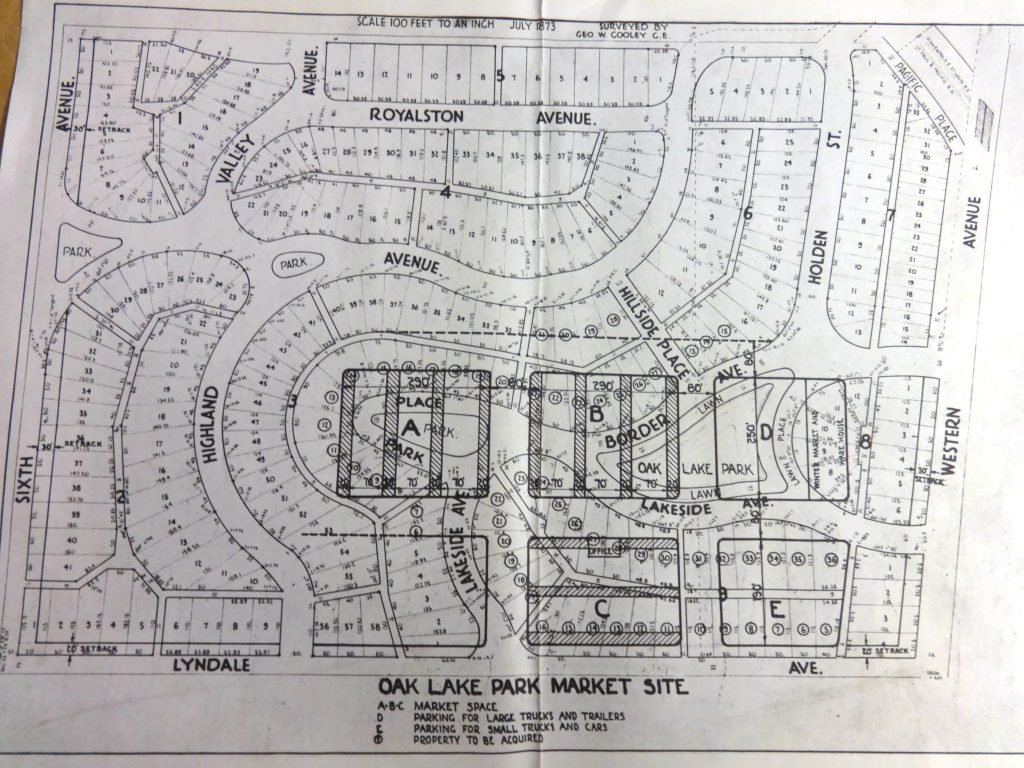

This map shows plans to destroy Oak Lake Park, an upscale Victorian neighborhood that had its glory years when Minneapolis was in its infancy. Today there is no trace of its curving streets and gingerbread-ornamented wooden homes. This diagram from the 1930s illuminates how the once-wealthy subdivision would soon be bulldozed to make way for a new farmer’s market on the edge of downtown.

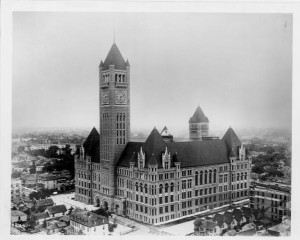

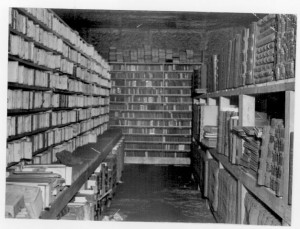

This plan is one of the thousands of treasures stored in the clock tower of our Romanesque-style City Hall. Few Minneapolitans are aware that a nineteenth century library looms above downtown, squeezed into a narrow space above the city offices and below the city hall clock. This is the attic of our city government. Crammed into this space is a century of records; it’s an eclectic collection of correspondence, ledgers, maps, surveys and photos that few researchers have examined.

Minneapolis City Hall shortly after its completion. From the Minneapolis photo collection, Hennepin County Central Library.

These records are an invaluable community legacy. Far more than the official record of city government, these holdings make it possible to see the dark complexity of our community and its struggles as it developed. Its archival cartons and map drawers hold glimpses of the past. We can see grandiose and unrealized redevelopment plans. We can document people and activities that were never recorded in any official histories, published documents or even newspaper reports.

Records on the fourth floor of Minneapolis City Hall, 1936. Photo is from the Minneapolis photo collection, Hennepin County Special Collections.

For the rest of this month, Historyapolis is going to bring you some of the highlights from this collection. Only a handful of people are familiar with these holdings, which should be recognized as an important community asset.

The Minneapolis City Archives are particularly critical for understanding our community’s history of urban redevelopment, which started, in earnest, with Oak Lake Park. When it was first developed in the 1870s, this neighborhood was home to some of the city’s most affluent residents. These were not the grand mansions of Park Avenue but rather than homes of successful professionals, like Dr. Augustus Harrison Salisbury, whose grandson Harrison Salisbury would grow up to become a world-famous foreign correspondent.

Residents of the leafy subdivision established the city’s first neighborhood association, which built a small bandstand next to the tiny Oak Lake. And they created the city’s second park, after Murphy Square. But the idyllic neighborhood was quickly overwhelmed by the growing city. Bordered by a growing network of railroads and an increasingly filthy Bassett Creek, Oak Lake Park rapidly fell from grace. People with means were pulled east by Loring Park, which had been designed in the 1880s by nationally-renowned landscape architect Horace Cleveland. By the first decade of the twentieth century, the neighborhood on the edge of downtown had become, in the words of Harrison Salisbury, “the most alien corner of that most Middle Western city of Minneapolis.”

Salisbury grew up in his grandfather’s house at 107 Royalston Avenue, when the neighborhood had lost the patina of prosperity. The budding journalist loved the racial and economic diversity of the Near North Side, later reflecting that this environment prepared him perfectly for his career as a foreign correspondent, especially his years in Soviet Russia. The corner of Sixth and Lyndale—shown on the bottom left of this map—was the center for Eastern-European Jewish life in the city while Salisbury was a boy. By the time he was in high school, the center of gravity for Jews had shifted north. This corner became the commercial and entertainment hub for the growing African American community in the city.

By the 1930s, the city had condemned Oak Lake Park as a slum. This neighborhood was the first target of a three-decade long urban renewal campaign in Minneapolis that would obliterate much of the city’s historic streetscape. Think about Oak Lake next time you visit the downtown Farmer’s Market. It lies buried under the concrete expanse, invisible to modern view.