Map Monday: Farewell to the Patrol Limits?

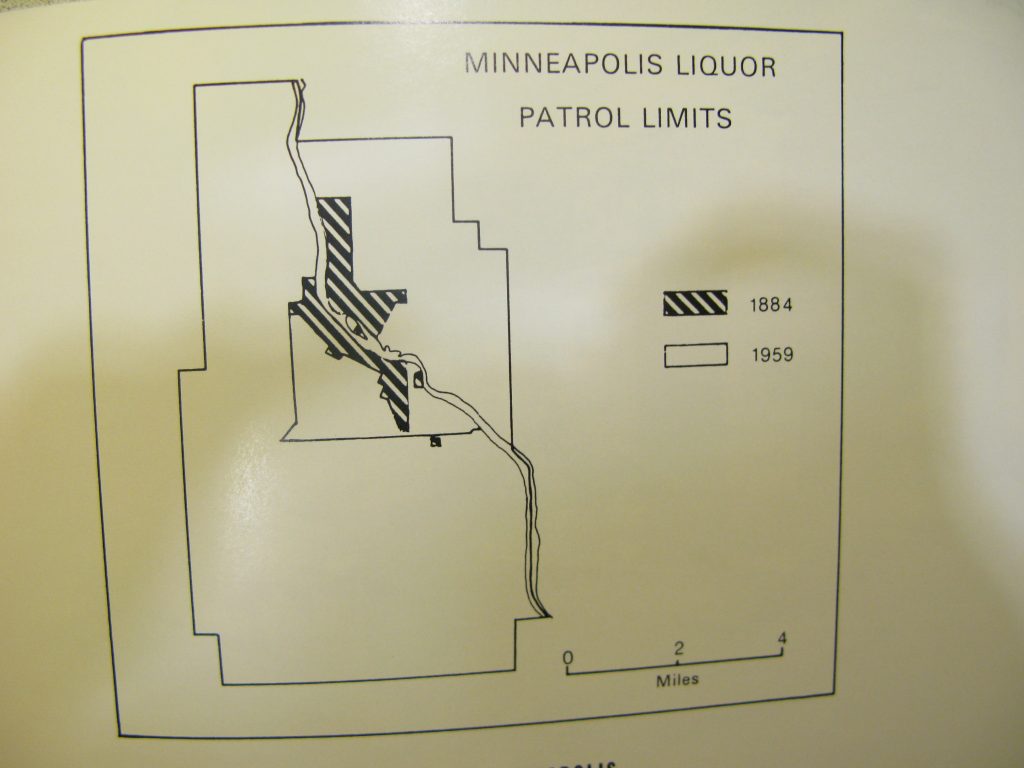

It’s Map Monday. Our diagram today shows the boundaries of the “liquor patrol limits” or the area where liquor sales were legal in Minneapolis for most of the twentieth century. This restriction–which was first incorporated into the city charter in 1884–has played a central role in the city’s politics and development since it was first enacted. When Minneapolis voters go to the polls tomorrow , they will decide whether to reject the last vestiges of this nineteenth century urban planning vision.

The 1884 “patrol limits” made Minneapolis unique. Other cities had banned alcohol. But Minneapolis charted what seemed like a pragmatic middle ground between prohibition and tolerance. Mayor George A. Pillsbury–who was part of the band of New England Yankees who controlled politics and industry in Minneapolis until World War II– led efforts to concentrate liquor sales into a small part of town, limiting what he believed to be the moral contagion of saloons and placating residents inspired by the swelling temperance movement who demanded that liquor be banned from their neighborhoods.

Under Pillsbury’s leadership, the cost of liquor licenses increased fivefold and bars were limited to the areas of the city that were oldest and most dominated by immigrants. They were allowed downtown around Bridge Square, the area that later became the Gateway District or Lower Loop. They were sanctioned in Northeast Minneapolis, home to many residents of German and Slavic descent. And they were tolerated along Cedar Avenue in Seven Corners–an area known as “Snoose Boulevard” that had the highest concentration of foreign-born residents in the city.

By 1902, Washington Avenue had become saloon row. One-third of the city’s licensed drinking establishments were located along a two miles stretch of this street between the railroad depots and Seven Corners. City leaders boasted that this tight concentration of bars benefitted both public safety and the public purse. A tiny police force was able to maintain order in the growing city.

Prohibition suspended legal liquor sales. But when they resumed in 1934, Minneapolis reinstated its patrol limits, which were expanded southward to Franklin Avenue in 1959. But it was clear that these tight restrictions seemed to encourage corruption. Multiple scandals involving liquor licenses, organized crime and city officials helped to discredit this zoning scheme in the eyes of voters, who voted to repeal the liquor patrol limits in 1974.

Even after the patrol limits were lifted, however, liquor licenses remained expensive and difficult to obtain. And until very recently, it was almost impossible to get permission to sell alcohol in neighborhood restaurants.

With tomorrow’s election, the age of the liquor patrol limits may finally come to an end. City voters are being asked to vote on the city’s “70/30” rule, which seeks to curtail drinking in residential neighborhoods. Restaurant owners have called for the suspension of the rule that requires them to earn 70 percent of their revenue from food instead of alcohol. I’m wondering whether Minneapolitans will finally banish a city planning ordinance conceived at the height of the nineteenth century temperance movement?

This map–and the information for this post–come from Jim Hathaway, who wrote a 1982 dissertation on liquor controls in the Twin Cities for the geography department at the University of Minnesota. His research was distilled into an article for Hennepin History Magazine that was published in the Fall of 1985. This map is from that publication.

[…] Twenty years after these images were created, Washington Avenue was known as saloon row. One-third of the city’s drinking establishments were located along this commercial artery, which became the backbone of one of the nation’s […]