Names matter: the story of Bde Maka Ska

Names matter. They serve as cultural signposts that articulate the social geography of a community. They declare who is remembered and who is revered.

And this is why the body of water now known as Lake Calhoun needs a new name. Or in this case, an old name that can help us understand the complex racial history of the land that became Minneapolis.

One of the jewels in the crown of the Minneapolis Parks, Lake Calhoun got its current name from a team of U.S. Army surveyors mapping the military reservation around the newly established Fort Snelling in the early nineteenth century. When they came to a lake that local people called Bde Maka Ska, which translates from Dakota to mean “white bank lake,” they paid no mind to established nomenclature. Instead, they designated the lake as “Calhoun” on their map to honor their patron, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun. This move planted the American flag on the region’s cultural terrain. It also curried favor with a powerful politician who would ultimately serve in both houses of Congresses and as Vice President and Secretary of State. In this way, a South Carolinian was written into the landscape of a place he would never visit.

Over the twenty years that followed, John C. Calhoun established himself as the nation’s most passionate proponent of race-based slavery. While many of his contemporaries defended slavery as a necessary evil, Calhoun declared that race-based bondage was “a good.” In a 1837 speech he asserted that “never before has the black race of Central Africa, from the dawn of history to the present day, attained a condition so civilized and so improved, not only physically, but morally and intellectually.”

Calhoun’s fiery oration likely would have met nods of assent among the officers at Fort Snelling. Many shared Calhoun’s southern heritage and had grown up in slave-holding families. And many of them owned slaves, since the U.S. Army provided a financial incentive for them to embrace the institution of human bondage. They drew bonus pay if they employed a “private servant,” a policy that encouraged them to buy and hold slaves at military installations across the country. Slavery was forbidden in the Northwest Territories, which included the land of the Dakota. But laws did not change the conditions for Courtney, Eliza, Mary, Louisa, William, Peter, some of the men and women we know labored in slavery at Fort Snelling.

Their stories are largely forgotten by Minnesotans, who think the bloody history of slavery hangs only around the neck of the South. But a group of Minneapolitans are challenging how our community pays homage to white supremacy. Mike Spangenberg started a petition on Change.org that calls on Minneapolis Park Commissioners to remove the Calhoun name from this Minneapolis lake. This petition builds on the efforts of Park Commissioner Brad Bourn, who has been demanding this change for years.

Spangenberg was inspired by this television report as well as the move in Alabama, South Carolina and Mississippi to remove the Confederate battle flag from public buildings. This comes after the massacre of nine African Americans in a Charleston church by a white supremacist who posed with the pennant and professed his desire to start a “race war.” The flag was conceived during a fratricidal war over slavery. Southern whites embraced it again as a response to the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

If South Carolina can grapple with how the past lives in the present, so can Minneapolis. If the Palmetto state can discard a bitterly-contested symbol of white supremacy, Lake Calhoun can become Lake Bde Maka.

Peeling away the Calhoun appellation would honor the early Minnesotans whose names have been lost to history. Courtney, Eliza, Mary, Louisa, William, Peter would have likely decried any attempt to describe their conditions of labor at Fort Snelling as “civilized” or intellectually elevated. And restoring the original name of the lake provides an opportunity for Minneapolitans to recognize that they live in the homeland of the Dakota.

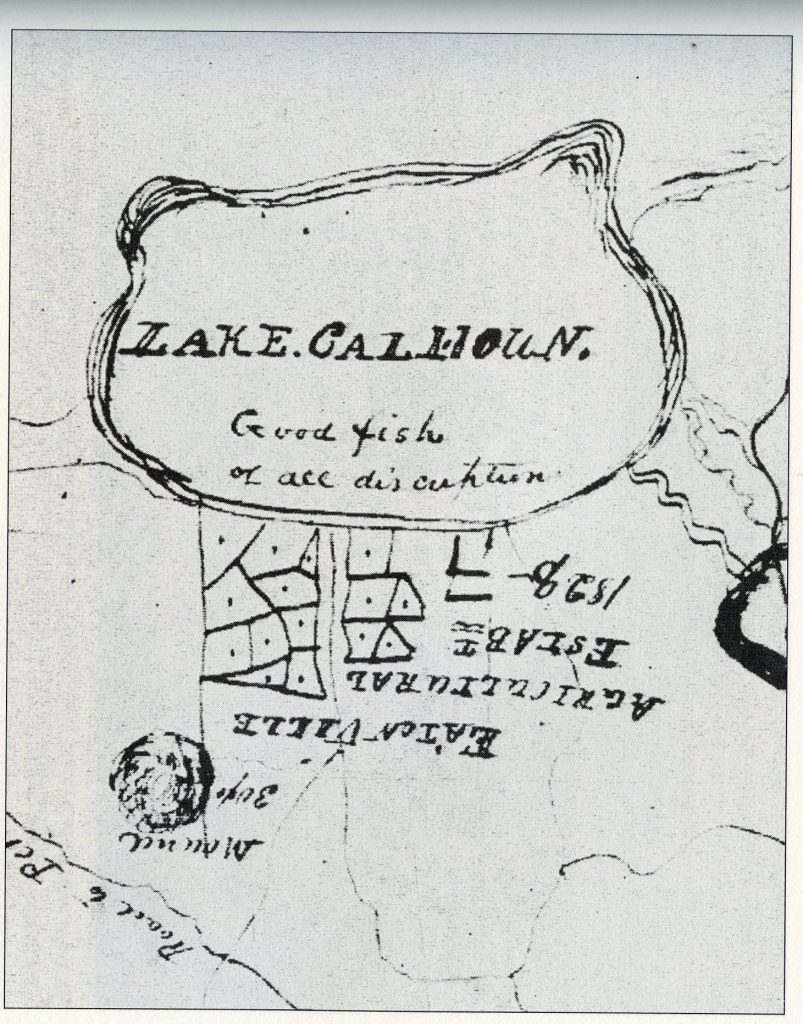

Native American historian and activist Kate Beane has spent years uncovering the story of her ancestors who lived on the shores of Bde Maka Ska in a village that was called Heyate Otunwe or Cloudman’s Village. Led by Mahpiya Wicasta, or Cloud Man, this settlement was an agricultural experiment that melded Native American lifeways with farming practices championed by American settlers. This was the place where the Dakota language was first systematically recorded on paper by missionaries Samuel and Gideon Pond. This 1835 map created by Indian agent Lawrence Taliaferro clearly shows this community on the lake. Taliaferro’s drawing–which is part of the collection of the Minnesota Historical Society–also describes the lake as having “good fish of all description.”

Though successful in many ways, the village was abandoned in 1839. Hostilities between the Ojibwe and Dakota had flared. Inhabitants feared they were too vulnerable to attack. Any trace of Cloud Man’s Village was buried for good when the lake was transformed from an unruly marsh to a manicured urban playground. While there is a small marker to the Pond brothers, nothing indicates the historic presence of the Dakota people.

Defenders of the Calhoun moniker argue the name illuminates the sometimes uncomfortable history of the land that became Minneapolis. But we can do better. We can make our modern urban commons reflect the broader currents of the past. As we struggle to understand the origins of our racial disparities, we need signposts that can guide us as we explore the histories submerged in the city of lakes.