“The Olympic winter sports games will be held in Minneapolis in 1928 or 1932”

In 1924, Glenwood Park in Minneapolis hosted the trials for the U.S. Olympic ski team. The success of this event prompted Minneapolis Park Superintendent Theodore Wirth to make a prediction in his report for that year. “The prospects are that the Olympic winter sports games will be held in Minneapolis in 1928 or 1932,” he declared.

Wirth’s optimism proved unfounded. The park that now bears his name would never see a full-fledged Olympic competition, though the city would continue to host Olympic trials for skiing and skating. City leaders failed to parlay community enthusiasm for winter sports into a bid to host the international games, perhaps because the city is rather short on the mountains necessary for alpine competition.

Yet even these geographic realities could not extinguish the Olympic dream in Minneapolis. Twenty years after Wirth saw a winter Olympics in the near future for Minneapolis, a group of business leaders conceived a sophisticated campaign to bring the 1952 summer Olympics to the city. This effort had little to do with athletics. Instead, it was inspired by the widespread desire to resuscitate the reputation of the Mill City.

This scheme was hatched, according to two reporters from Esquire magazine who were covering the Olympic selection process, by “a few newspapermen in a popular Mill Town eatery back in 1944.” The city demonstrated its commitment to this offer by sending a team to Switzerland to make its case. It then hosted the 1946 NCAA track meet at the University of Minnesota , in the hopes of getting the track and field community in its camp. That same year, the city pulled out all the stops for a visit by Bo Eckelund, the Swedish delegate to the International Olympic Committee.

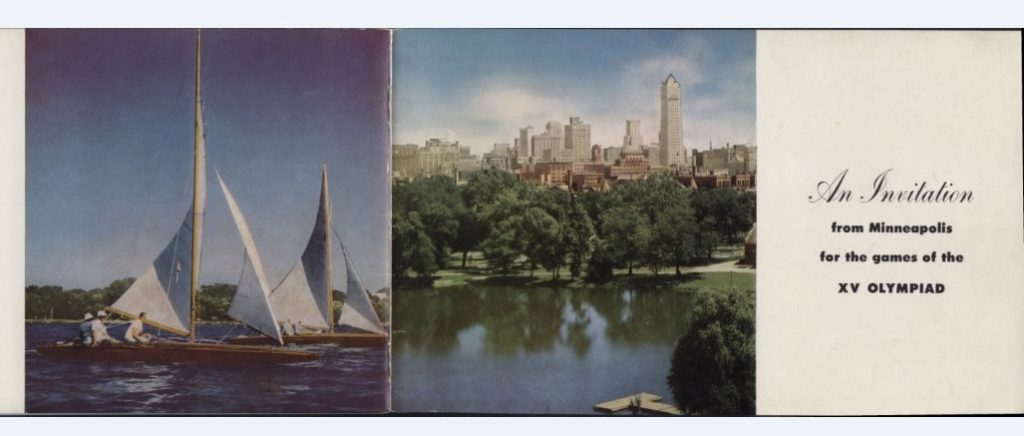

The city’s most impressive gambit, according to the Esquire journalists, was a slick pamphlet touting the Minneapolis Armory, the University of Minnesota Stadium, the Minneapolis Auditorium, Fort Snelling and Lake Minnetonka as venues for Olympic events. It used spare text and modern graphics to show how the city already had “every major facility necessary to the traditionally fine conduct of this great international event” and could easily “construct or adapt other facilities required.” Printed in English, French and Spanish, the booklet was delivered by air mail to athletic officials throughout the world. “You can wager your gold fillings that such a gimmick cost a mound of dough,” the Esquire writers asserted in April, 1947.

Their description made no mention of the still obscure mayor of Minneapolis, Hubert H. Humphrey, the only politician on the Olympic Invitation Committee of Minneapolis. One year after their dispatch, Humphrey burst onto the national political scene when he delivered a clarion call for civil rights to the 1948 Democratic National Convention. Like former Newark mayor Corey Booker today, the young chief executive of Minneapolis proved expert at garnering headlines. Journalists of the time described him as a “brash, young tornado” and the “most extraordinary politician that Minnesota produced in fifty years.”

As soon as he moved into Minneapolis City Hall, Humphrey began working with the powerful business community to repair the civic reputation of Minneapolis. Since Lincoln Steffens had illuminated the city’s dysfunction in his “Shame of the Cities” series for McClure’s magazine in 1903, Minneapolis had been dogged by dark associations with organized crime, political corruption, labor strife and racial intolerance. Humphrey focused on changing the city’s social climate. He combined vigorous support for racial justice with a fresh intolerance for gangsters and political radicals, whose influence had waxed since the success of the Teamsters’ Strike in 1934. The Olympic Invitation Committee–along with an effort to convince the new United Nations to locate in the Mill City –was undoubtedly part of Humphrey’s larger effort.

These aspiring Olympic hosts believed that the glow of an Olympic torch would banish shadows cast over the city by corruption, intolerance, and employer repression. Ten days of athletic contests and international fellowship would recast the city as a commercial powerhouse and “great vacation area of 10,000 lakes, temperate climate and hospitable people,” in the words of their brochure. The benefits of this transformation were obvious to the business community, which thought that a Minneapolis Olympics would conjure up warm associations for consumers weighing the merits of Cheerios versus Quaker Oats.

The American journalists covering the selection process thought Minneapolis faced its stiffest competition from Detroit, another town with a powerful business community and a highly developed public relations machine. But when the 1948 International Olympic Committee convened in Stockholm, the Mill City lost out to Helsinki, Finland. Olympic organizers were eager to find a location where athletes from east and west could compete, transcending tensions between the United States and the USSR. The escalating Cold War meant that geopolitical concerns outstripped American salesmanship.

Material for this column–including the brochure from the Olympic Invitation Committee of Minneapolis– is from the vertical files at the Minneapolis Collection, Hennepin County Central Library. The quote from Theodore Wirth is from David C. Smith’s Minneapolis Park History.