The President Streets

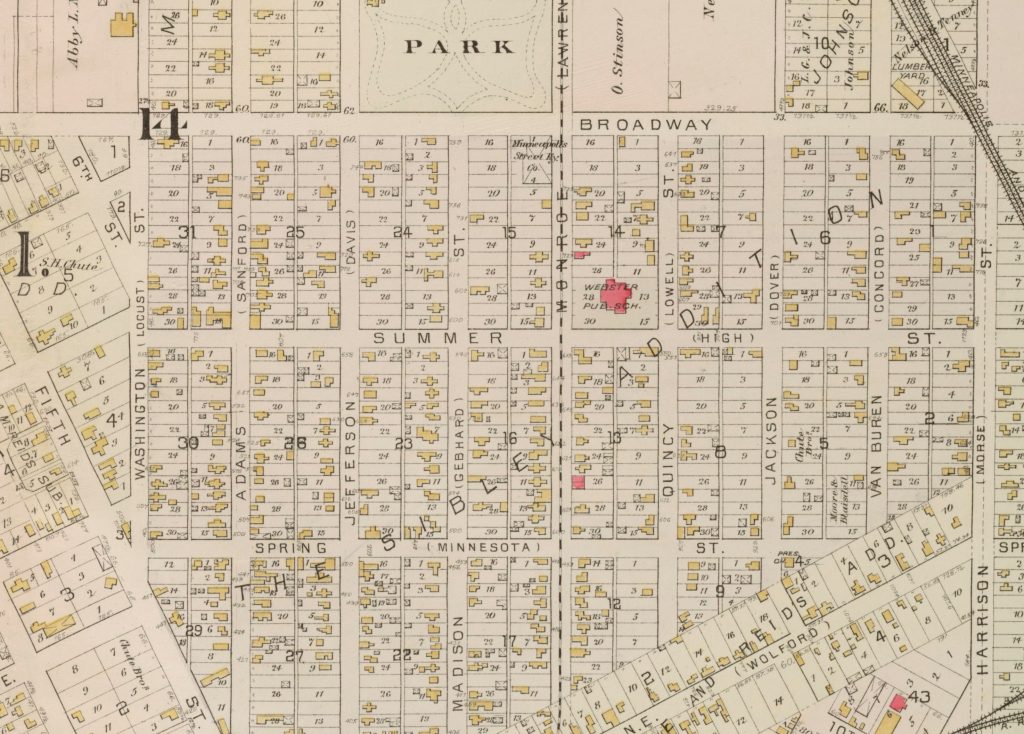

It’s map Monday. And of course, it’s also President’s Day. So here we have a detail from an 1885 map of Northeast Minneapolis that focuses on the President Streets.

Most Minneapolitans know this neighborhood in Nordeast, where you can learn your presidents–and the order in which they were elected–by walking east on Broadway. The street series starts, of course, with Washington. The next street is Adams, followed by Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Quincy, Jackson, Van Buren, Harrison and so on. This nomenclature was designed to provide an ambulatory history lesson for a neighborhood which has traditionally been home to many immigrants.

I had heard–from several sources–that it was anxieties about these immigrants that prompted city leaders to create the President Streets around World War I. Yet this plat map–created by Griffin Morgan Hopkins in 1885–shows that the President Streets were created much earlier, well before the local Americanization campaign reached its apex.

The Minneapolis Tribune reveals that the President Streets were established in 1872, when Minneapolis and St. Anthony were consolidated into one municipality. “With the union of the two cities the necessity of a change in the system of naming streets and avenues becomes apparent to nearly every one, although all may not agree as to what that change should be,” the newspaper wrote on February 27, 1872. “In old Minneapolis there are several streets of the same name in different parts of the city, and there are few who can tell the location of a majority of the streets. To meet the necessities of the case, and enable old settlers and new ones to tell the location of almost any street mentioned by its name, Franklin Cook, Esq. and others have prepared a plan which will probably find favor on both sides of the river.”

The President Streets were part of a larger plan to rationalize the street grid, according to a scheme that was “thought to embody the best features of that now in New York as well as Philadelphia.” It divided the city into four quadrants. Roads running away from the river were called avenues; those parallel with the river were streets. “Every block shall commence with an even hundred” and house numbering would conform to the streets. In other words, “a person living at 925 Tenth Street will live between Ninth and Tenth Avenue.”

While the new system was adopted it was not without controversy. Yet its defenders were steadfast in the face of those who denounced the reforms as unnecessary, wasteful and confusing. “Minneapolis is one of the handsomest, neatest, most symmetrical cities on the continent and beautifully adapted to the new nomenclature. Shall this city henceforth be a jungle and labyrinth for the stranger to get lost in, or shall it be so systematically laid out as to be a clear path to every man’s foot?” the Tribune editorialized in January, 1873. “Is it possible that there are any among us wishing to abandon so admirable a reform?”

While it was never abandoned, this reform took some time to be universally adopted. This map includes, in parenthesis, next to each President’s name, the street’s original name. Look carefully and you can see that Washington was Locust and Adams was Sanford. More than a decade after the city embraced the great “street nomenclature reform,” this map suggests that some Minneapolitans continued to cling to their original street names. Fifteen years later, however, these names were almost forgotten. This prompted the Tribune to write a feature in 1899 recounting the city’s early geographic nomenclature.

The 1885 Hopkins plat map is Minneapolis collection at the Hennepin County Central Library and digitized on the Minnesota Digital Library. My thanks to James Eli Shiffer, who came up with the idea for this post.