Who was Floyd Olson?

In August, 1936, Minneapolis lost a native son. “One arid afternoon, the people buried Floyd Olson under the trees by a lake,” journalist Eric Sevareid remembered. “When the news hawkers shouted the announcement from their corners, the noises of the street died down and their voices with the shocking sentence were unbearably loud and distinct in the unnatural stillness. I saw a streetcar motorman get down from his car and walk back from the newsstand with tears streaming down his cheeks. Many thousands had a feeling that someone in their family had died.”

Mourners outside Memorial Auditorium in downtown Minneapolis, August 26, 1936. Image from the Minnesota Historical Society.

Mourners massed in the Municipal Auditorium to commemorate Olson’s legacy. A more intimate group gathered at Lakewood Cemetery to lay him to rest in a glass-topped coffin.

During that hot summer week, the city gave itself to bereavement. But not everyone was as sad as the motorman–or Sevareid– to say goodbye to the 44-year-old governor of Minnesota. The populist politician was reviled by many who saw him as a ruthless demagogue who had served at the behest of the city’s crime bosses.

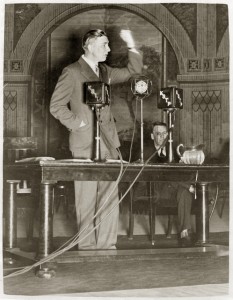

During the darkest days of the Great Depression, Olson had come to embody hope for Americans seeking real economic and political change in the United States. A compelling orator and charismatic personality, Olson was a masterful coalition-builder. Most important to young people like Sevareid who wanted fundamental transformation of the political and economic system, he was not afraid to call for dramatic action in the wake of the worldwide economic collapse. “I am not a liberal,” Olson declared to the Farmer-Labor convention in 1934. “I am what I want to be–a radical.”

The son of Scandinavian immigrants, Olson had grown up on the near North Side of Minneapolis, surrounded by Jewish and African-American neighbors. He was trusted in the neighborhood as a Shabbos Goy, a person employed by observant Jews to light candles and do other household tasks on the Sabbath, when they are forbidden to do any kind of work. Olson’s father had steady work on the railroad that kept his family out of poverty. But his home was located in a quarter of the city viewed by many as a terrible slum. In fact, the year after his death, his block was bulldozed in one of the city’s first effort to clear urban blight; this became the site of the Sumner Homes, the first federally funded housing project in Minnesota.

Birthplace of Governor Floyd B. Olson, razed for Sumner Field Homes. The city published this image in the newspaper to show that “even governors’ birthplaces can be fire hazards.” Image from the Special Collections Department of Hennepin County Library.

Olson spent a desultory year at the University of Minnesota. Then he drifted around the continent working as a longshoreman, miner and harvest hand. He returned to Minneapolis to study law and by 1920 was Hennepin County Attorney. Over the decade that followed, his career as the county’s top law enforcement man bore the stamp of his formative years in one of the most diverse neighborhoods in Minnesota.

Olson was keenly aware of the dangers of the Ku Klux Klan, which was attracting a popular following in Minneapolis in the early 1920s. He used his position as Hennepin County Attorney to expose the secret white supremacist organization. Olson’s successful crusade earned him the sustained support of the city’s Jewish community as well as emerging African-American activists like Lena Olive Smith, who would later lead the city’s NAACP.

But for those Minneapolitans who believed that North Minneapolis “provided most of the city’s criminals and crooked politicians,” Olson’s northside roots made him suspect. The County Attorney was guilty by association with a part of Minneapolis known for its gambling houses, brothels and after-hours tippling spots. His critics pointed to this personal history when they blamed him for the growth of crime and corruption during the first decade of Prohibition. They turned a blind eye to geography (the city’s proximity to Canada helped to make it a center for the illicit liquor trade). Instead, The Chicago Tribune–under the leadership of Robert McCormick–argued that the “career of Floyd B. Olson as prosecuting attorney of Hennepin County between 1920 and 1930 parallels the growth of organized crime.”

Olson was no advocate of Prohibition. And to be effective in Minneapolis politics in the 1920s, he needed to be able to work with its powerful criminal elements. But his most troubling flaw, in my opinion, was his opposition to a free press. He worked to silence those who linked him to the city’s underworld. And he even made a personal appearance at the Minnesota Supreme Court to champion a law that gave the state right to suppress publications viewed as undesirable. He argued that “freedom of speech is not an absolute right”; this logic was rejected by the United States Supreme Court in 1931.

The ruling did little to protect reform-minded writers; three Minneapolis journalists were murdered between 1934 and 1945. Critics castigated Olson for refusing to pursue the killers in the first two cases.

Olson’s political career was ascendant when he was diagnosed with inoperable pancreatic cancer at the end of 1935. Already serving as governor, Olson was on the cusp of winning a seat in the United States Senate. Many Americans held him up as the great hope for a dark decade, the person best suited to challenge Franklin Roosevelt as a third-party presidential candidate. Olson’s death punctured this vision. “I walked out into the parched, lifeless streets with a numb feeling of dismay,” Sevareid remembered. “Could one never win? How weak we were, when so much had depended upon one human being.”

Olson could be remembered as the Paul Wellstone of his time, a populist political maverick silenced by tragedy at the apex of his influence. But Olson remains a cipher to me. It is impossible to predict the kind of leader he would have become with the end of the Great Depression and the onset of World War II. This is food for thought during a drive down Olson Memorial Highway, through the neighborhood that helped to shape the young politician into one of the most complex figures in Minnesota political history.

Material from this post was taken from Eric Sevareid, Not So Wild a Dream (New York: Atheneum, 1976):. 71-72; George Mayer, The Political Career of Floyd B. Olson (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987); Marda Liggett Woodbury, Stopping the Presses: The Murder of Walter W. Liggett (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998); “Murder in Minneapolis,” The Chicago Tribune, February 2, 1936; “Lena Smith Among Governor Floyd Olson Supporters,” Twin Cities Herald, November 12, 1932; Floyd B. Olson House, National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form, 1914 West 49th Street, Minneapolis, December 31, 1974.