“The Joys of Camp Life”: Vacation at Mendoza Beach

Labor Day means that summer is over. Sad as I am to say goodbye to warm weather and a relaxed schedule, I count myself lucky that I enjoyed lots of vacation time during this lovely time of year. Which makes me very different from working women in Minneapolis at the beginning of the twentieth century.

In 1909, most young women in Minneapolis had no chance to relax or enjoy the “open air” during the short summer months. A group of female reformers associated with the Young Women’s Christian Association resolved to address this problem. They established a tent colony on the shores of Lake Calhoun that allowed girls to experience the “joys of camp life.”

Those lucky enough to get a berth at this camp got on the streetcar downtown. They rode for thirty minutes until they reached Dean Parkway, disembarking at what was known as Mendoza Beach. In 1912, the Minneapolis Park Board made this section of Lake Calhoun into a resort-style beach; it enhanced the swimming area and constructed a state-of-the art beach house with changing rooms, lockers and showers.

To maintain propriety at this new public facility, the park board required all female swimmers to don a regulation jersey swimming suit that included full length tights under a snug tunic. (And this impossibly cumbersome outfit drew howls of protest from social conservatives in the city, but I digress).

This was more than a decade before construction started on the towering Calhoun Beach Club. Though inside the city limits, the beach house was surrounded by fields and woods. The result was a streetcar summer resort for the people.

Across the street from the beach house was the YWCA camp. Five canvas tents provided sleeping quarters for thirty-five girls, who slept on cots and ate in a communal dining tent. Campers stayed for a week. They spent their vacation in bare feet, wandering the woods or wading in the water. They rowed, swam, hiked and read. They ate dinner. They roasted marshmallows. One newspaper report asserted that they started each day at dawn with “dew baths” in the adjacent woods.

Women at summer YWCA at Lake Calhoun. YWCA Collection at the Social Welfare History Archives, University of Minnesota.

But I wonder. My guess is that the campers would have welcomed the chance to slumber uninterrupted. Every other week of the year they got up early to work in the city’s factories. The girls at the YWCA camp were part of the huge population of young working women struggling to make it on their own in the city. By the early twentieth century, Minneapolis had more single working women than almost any other community in the country. And long before the iconic Mary Tyler Moore fixed Minneapolis in the national imagination as a home for independent women, these women were forging a new kind of path for their sex.

Single women in search of economic opportunity had been drawn to Minneapolis from all points on the map. But the city was an especially powerful magnet for women from the surrounding rural hinterlands, who left farms in search of financial and social independence impossible in small towns.

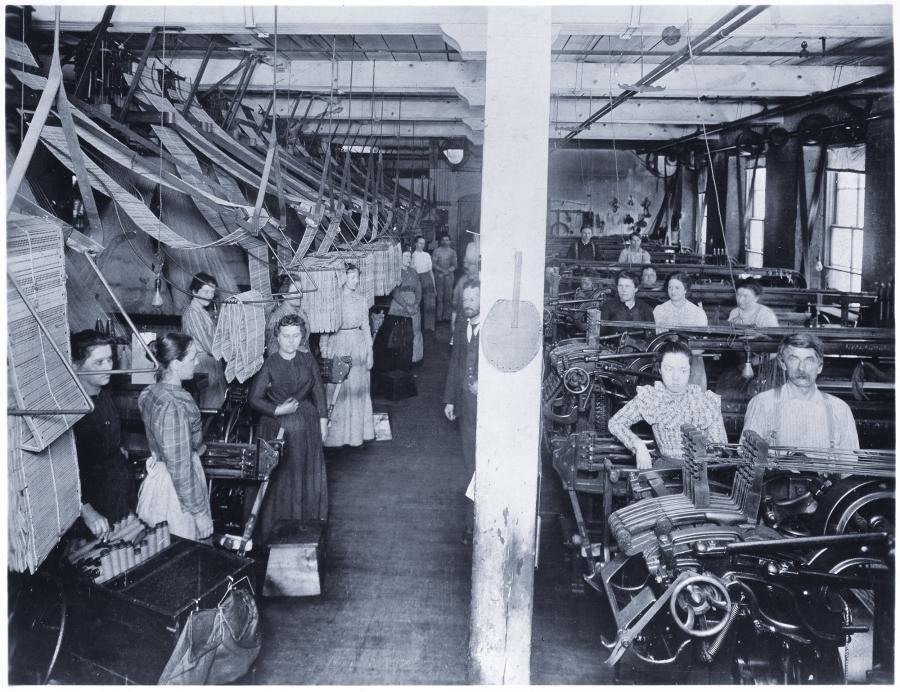

Employment opportunities were plentiful but hardly lucrative for women in the city. Some young girls resigned themselves to domestic service. And some lucky women typed letters or took dictation. But most female wage-laborers did piece work of one kind or another in the factories near the Mississippi River. They sewed cloth bags for flour and mattress covers. They stitched shirts. They steamed laundry. They wove luxurious and stylish blankets for travelers on the Pullman Palace railroad cars.

The products were different but the same grim conditions prevailed. These young women labored ten to twelve hours a day in workshops that were humid and dusty and dark. They had meager lunch fare and no time to eat. They were hot in the summer and cold in the winter. They made barely enough to pay for room and board. Often their wages fell short.

Sleeping on a cot in a canvas tent with seven other women was heaven by comparison. Even when it rained.

Campers at Lake Calhoun summer camp. From the collections of the YWCA, Social Welfare History Archives, University of Minnesota.

In 1914, the camp moved from Dean Parkway to a more secluded location at the intersection of 28th street and Upton Avenue. The camp remained in operation in this location until 1919, when the YWCA was given land outside the city on which it built a more permanent facility.

Sources: YWCA scrapbook, Box 12, YWCA Collection, Social Welfare History Archives, University of Minnesota; Joanne J. Meyerowitz, Women Adrift: Independent Wage Earners in Chicago, 1880-1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988).