“Laughing Water and Solemn Sioux”: The Vanishing Indian in the Dakota homeland

This week Minneapolis marked “indigenous people’s day,” a holiday conceived as a counter-celebration to Columbus Day. This commemoration serves as a reminder that we live in the land of the Dakota, who were pushed out of the area in the formative years of the metropolis.

When Permelia Atwater moved to St. Anthony in 1850, “the Indians were always about the town, and were friendly and sociable in their peculiarly quiet way,” she remembered. “They would enter houses without the least ceremony, going up or down stairs as the whim took them.” Just across the river in the area that would become Minneapolis, the land remained in Dakota hands until 1851. Native American tipis were a common sight until the Civil War.

Early settlers like Permelia never imagined that their first neighbors would remain in the growing city. Instead, they saw the indigenous inhabitants as part and parcel of the quickly vanishing frontier landscape. Residents like Permelia sought to speed this process, welcoming any and all signs of civilization, including the disappearance of native peoples.

They people who created St. Anthony envisioned a new kind of community for Minnesota. It would stand in stark contrast to the polyglot jumble that was St. Paul, which had taken shape around the Indian trade. By contrast, Minneapolis would be a modern manufacturing city guided by Yankee commercial and cultural values.”We could not fall back, as our St. Paul friends did, on the resources gathered from the Indian payments,” settler John Stevens explained in his autobiography. “Even at that early day St. Paul was commercial: we were manufacturing.” This vision articulated by Stevens was as much about culture as economics. Minneapolis may have been a city on the river. But inhabitants wanted it to be a city on a hill. And in mid-nineteenth century America, there was no virtue in the mixing of races.

Yet even as city leaders pushed the original inhabitants west, they embraced another kind of Indian. These Native Americans were fictional–the creation of a New Englander who had never visited Minnesota. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow had immortalized a cast of noble Indians in his epic poem narrating the love story of Hiawatha and Minnehaha. The publication of The Song of Hiawatha in 1855 sparked what could only be described as a literary cult.

This 1907 postcard juxtaposes images of Minnehaha Falls with Native Americans and Henry Longfellow. Longfellow’s 1855 poem sparked what can only be described as a literary cult, which remained robust well into the twentieth century. This postcard is from the collection of the New York Public Library.

Longfellow’s poetry was inspired by a daguerreotype of Minnehaha Falls created in 1851. And when the poem proved wildly popular, city leaders latched on to this phenomenon. They plucked names–Minnehaha, Hiawatha and Nokomis–from Longfellow’s pages to fasten on their quickly developing streetscape.

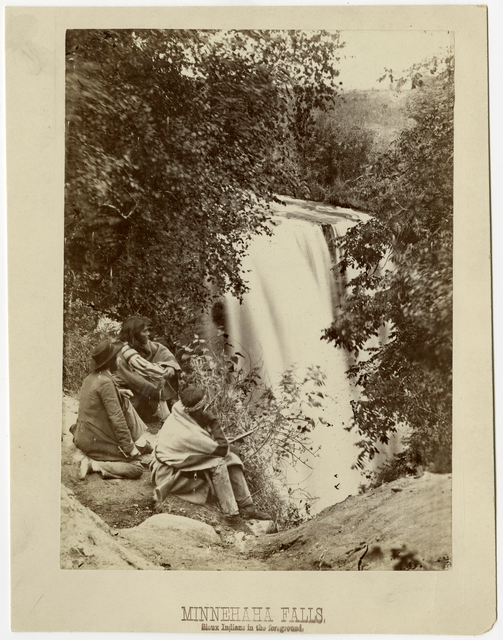

Two years after the publication of this epic poem, veteran journalist Edward Bromley sought to capitalize on this cult of Hiawatha with the image at the top of this post. Titled “Laughing Water and Solemn Sioux,” it showed three men sitting by the waterfall made legendary by Longfellow. It captures a critical moment of transition for Native Americans. It shows this brief window of time in the young city when flesh-and-blood Indians still walked this landscape. They had not yet been reduced to icons.

“When this picture was made,” Bromley asserted, “Indian wigwams dotted the landscape o’er in the vicinity of Fort Snelling and Minnehaha. The artist induced two of the dusky warriors. . .to sit within the scope of his camera.”

Dakota internment camp at Fort Snelling, 1862-63. Image is from the collection of the Minnesota Historical Society.

Five short years later, the only Native Americans in the area were confined behind a stockade fence on the flats below the fort. This was the site of the internment camp that housed 1,600 Dakota captured during the war that flared up on the prairie in the summer of 1862. Hundreds of the camp’s inhabitants died during the winter of 1862-63. Those who survived were removed to a site of even greater suffering in South Dakota.

Postcard is from the collection of the New York Public Library. Other images are from the collection of the Minnesota Historical Society. Quotes were drawn from Permelia Atwater, “Pioneer Life in Minneapolis–from a Woman’s Standpoint,” in History of Minneapolis, Isaac Atwater, ed (1893): 68; John Stevens, Personal Recollections, 88; “Obituary of Alexander Hesler,” Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin (New York, 1895).