The forgotten campaign of Jack Baker

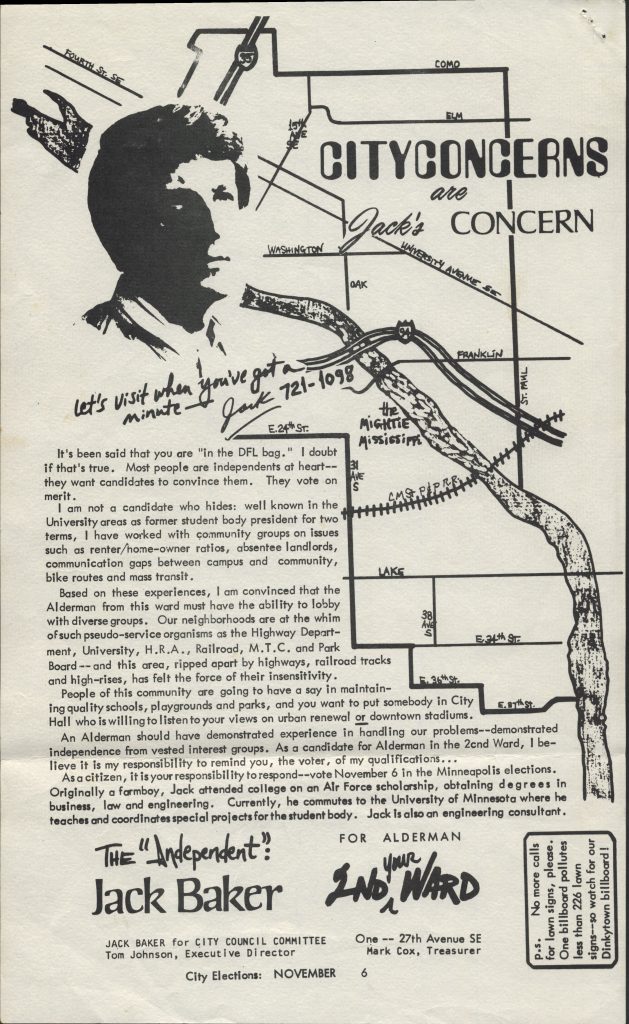

Yesterday was election day. The polls were pretty quiet in Minneapolis. But this civic occasion gives us an opportunity to revisit a long-forgotten political campaign. This broadside was created by Jack Baker, a candidate for Second Ward Alderman in 1973.

This leaflet casts Baker as a fairly conventional political candidate, though he was running as an independent in a heavily DFL ward. It touts his career in the Air Force and his degrees in business, law and engineering. It boasts of his success at the University of Minnesota, where he served two terms as student body president. It speaks to the concerns of voters in this neighborhood by the Mississippi River, which was being re-made by a series of urban renewal projects directed by the Highway Department, the University of Minnesota and the city of Minneapolis.

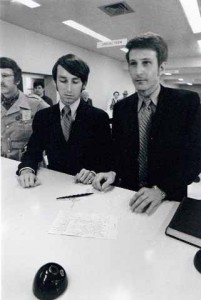

This campaign literature gives no clue that Baker was already a celebrity when he made his bid for public office. Three years earlier, Baker had won national attention for his efforts to win legal sanction for his union with Michael McConnell. On May 18, 1970, the couple donned matching white shirts and ties. They went to the courthouse in Minneapolis City Hall, where they paid a $10 fee to apply for a marriage license. As the media watched, court officials denied their request to be legally wed as a same-sex couple.

On May 18, 1970, Jack Baker and Michael McConnell applied for a marriage license in Hennepin County. Photo is from the collection of the Minnesota Historical Society.

The men persisted in their quest but were dismissed by courts and queer activists alike, who dismissed the couple as “crazies” for their fixation on marriage. They appealed first to the Hennepin County District Court and then to the Minnesota Supreme Court, which declared that “the institution of marriage as a union of man and woman, uniquely involving the procreation and rearing of children within a family, is as old as the Book of Genesis.” When their case was brought to the United States Supreme Court it was dismissed with a one-sentence ruling on October 10, 1972.

Their ground-breaking crusade cost McConnell his job as a librarian at the University of Minnesota, which went to court to defend its right to deny employment to open homosexuals. And this courageous stance did little to boost the political career of Baker. Baker lost his campaign, coming in fourth in a six-way race decided on November 6th. He garnered only 1044 votes and was defeated by Thomas Johnson.

Baker had posed in high heels for his campaign for student body president at the University of Minnesota, where he helped to found FREE (Fight Repression of Erotic Expression), an organization that fought for gay rights on campus. But Baker’s campaign for City Council muted any reference to queer politics. He focused instead on the built environment of the city, calling for greater use of bicycles and a community embrace of the Mississippi River. The river’s “garbage encrusted shoreline ought to be transformed into a place for Funky People to escape the traffic; to encounter wild things quietly, kindly.”

Baker’s bid for public office has been forgotten today. But with the hindsight of forty years, the vision he articulated for Minneapolis during his campaign seems prescient. With its bikes and newly revitalized riverfront and its influential queer political community, Minneapolis has become in many ways the model metropolis he imagined.

These campaign broadsides are from the private collection of historian Donald Gustafson. For more about the life and political legacy of Baker and McConnell, visit the Tretter Collection at the University of Minnesota, which recently received the couple’s papers. The men have also told their story in The Wedding Heard ‘Round the World, a book that will be released from the University of Minnesota Press next spring.