Prospect Park was not the only Minneapolis neighborhood to experience racial turmoil in 1909. Linden Hills erupted in protest when one resident decided to retaliate against her neighbors by selling her home to an African-American newcomer to the city. When Marie Canfield announced that Methodist Reverend William S. Malone had purchased 4441 Zenith Avenue, neighbors were enraged. Vandals shattered the home’s windows. And the white minister of the Western Avenue Methodist Church condemned the temerity of the African-American buyer. “Black people should avoid going into a community where their presence is irritating,” he told his parishioners.

Earlier in the year, Canfield had sued the New England Furniture Company for selling her a faulty stove with a gas leak. At the trial, three of Canfield’s neighbors testified that she was frequent user of opiates. She lost her case, and was fined by the court. Her response was to list her property–in the growing streetcar suburb on the West side of Lake Harriet–“for sale to negroes only.” The resulting ruckus was closely followed by the Minneapolis Tribune, which nicknamed the property the “Spite House.”

Neighbors decided to fight the sale, hiring an attorney to represent their interests. Their choice was strategic. They tapped William R. Morris, one of Minneapolis’s few African-American attorneys. Born in Kentucky to former slaves, Morris graduated from law school in Chicago, and moved to Minneapolis in 1889. Morris became the executive chairman of the newly-founded Minneapolis NAACP in 1914, and was a leader in the local black community. By hiring Morris, the neighborhood association legitimized their mission to the city’s established black community. The following Sunday, Rev. Wharton of the Minneapolis African Methodist Church preached: “there is no necessity of our thrusting ourselves where we are obnoxious to others and can never feel at home.”

An outsider to the city’s small African-American middle class, Malone had planned to start a small mission at 707 Washington Avenue. Malone’s mission in a poor, working class neighborhood conflicted with the African Methodist Church’s image of black respectability. Wealthier blacks like Morris and Wharton helped build an image of middle-class respectability for the small black community in Minneapolis. They were eager to distance themselves from Malone, bolstering their own reputations in the process.

The neighbors tried to raise money to buy the Canfield house from Malone. Before they reached a settlement, the Hennepin County sheriff seized the property. Canfield had not paid the judgment from her lawsuit against New England Furniture Company, so the county took the property. After the seizure, Canfield sold the property to the neighborhood association, cutting out Malone. The Tribune reported: “By the payment of good, hard coin, the residents of Linden Hills have averted the establishment of a ‘dark town’ in their midst.”

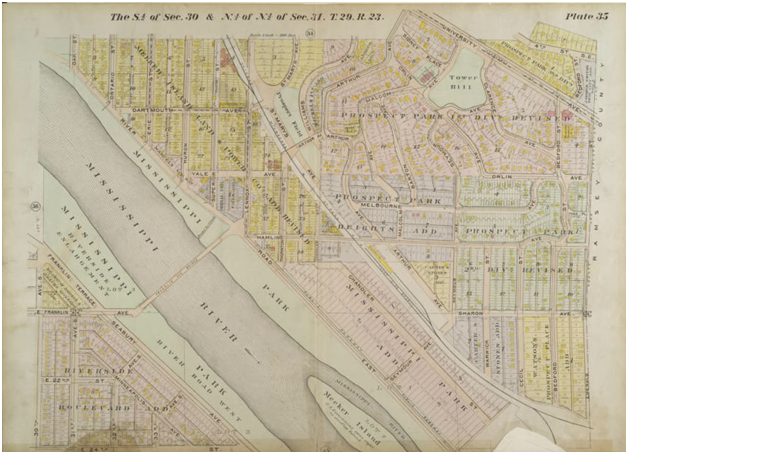

Image is from the Minneapolis Tribune, December 28th, 1909. Proquest Historical Newspapers. Access provided by St. Olaf College.

This post was written by Historyapolis intern Derek Waller, who researched the origins of residential segregation in Minneapolis for his January term project at St. Olaf College. Waller is continuing his research into this and other incidents, which he will present as part of a senior capstone paper.