It’s Map Monday. Our guest blogger today is Daniel Bergin, Senior Producer at Twin Cities Public Television and the director/producer of “Cornerstones: A History of North Minneapolis.” First broadcast in 2011 on TPT’s Minnesota channel, this documentary about the history of the enclave known as the “Northside” was co-produced by TPT and the University of Minnesota’s Urban Research and Outreach-Engagement Center (UROC). Bergin writes here about two maps he found while researching “Cornerstones” and what they can and cannot reveal about the city’s near North side.

Maps can present context, scale and scope. But it often takes the voice of the people to provide a meaningful ‘legend’ to interpret what cannot be conveyed in the abstract representations of a map.

In producing “Cornerstones,” I came across two different maps that provide better understanding of this storied section of the city. But it was the voices of the people that helped me understand what these maps conveyed and what they obscured.

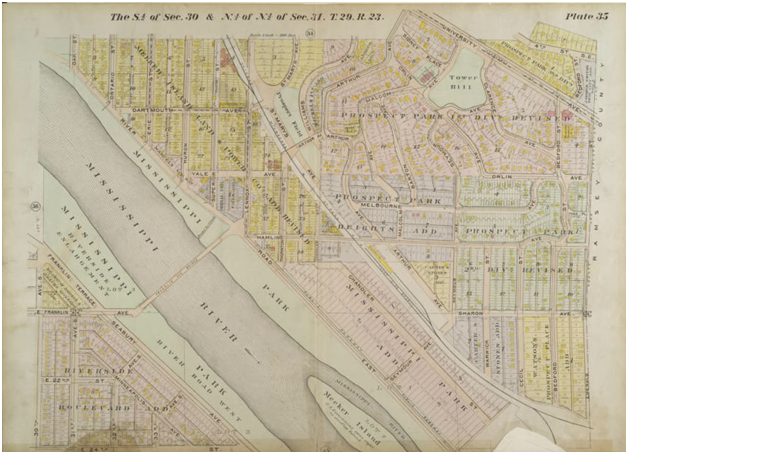

Both maps show Sumner Field, an area of near North Minneapolis that has been reshaped several times in the last century and a half. This multi-block area’s built environment and landscape has evolved from ramshackle, immigrant housing to the pleasantly manicured and landscaped community that is today’s Heritage Park.

A common element throughout this evolution, however, is the green space known as Sumner Field. This approximate area is seen in both of these maps.

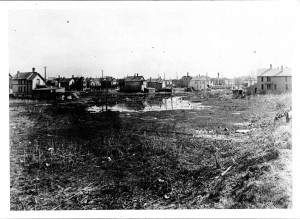

Sumner Field, before construction, c. 1930s. From the collection of the Hennepin County Library Special Collections, uncatalogued newspaper photos. Thanks to Rita Yeada for digitizing.

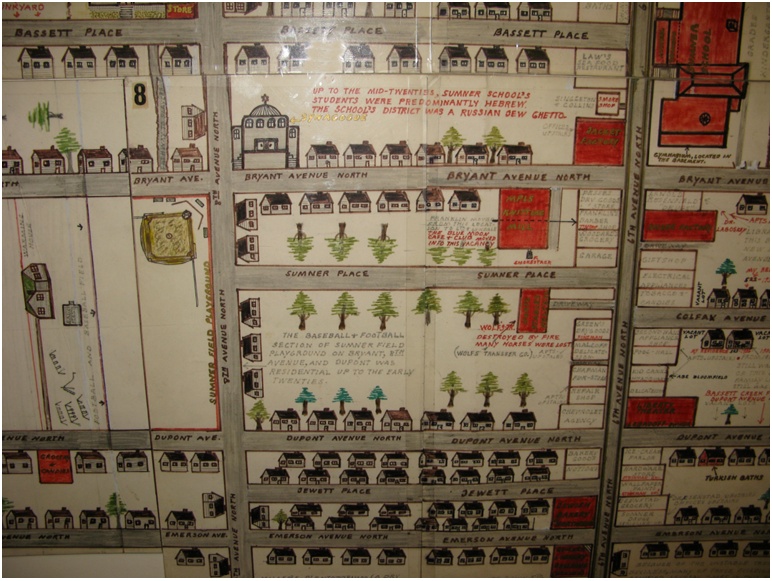

The map at the top was hand-drawn creation by Northsider Clarence Miller. His graphic curio is on display at the historic Sumner Branch library. Sumner Field is the center of this brilliant layman’s map. One gets the sense that this meticulously crafted folk-artwork is as much a quilt as it is a map.

Miller’s map shows Sumner Field before the area was bulldozed to create a federally-funded housing project during the Works Progress Administration of the 1930s. Sumner Field was the first federally-funded housing project in the city of Minneapolis. This map shows the new development as imagined by planners and promoters:

This overhead view–taken from a promotional brochure for the new development–provides a sense of the multi-dwelling units, their relationship to each other and the footprint of the development. What the map does not show is the human geography of the new development, which was designed to be segregated by race. As University of Minnesota professor Kate Solomonson explained, there were “particular parts of Sumner Field Homes that were for African Americans, another section, a larger section, for what they called ‘mixed whites.’”

Neither map illuminates the racial boundaries that were seen as necessary for social order in the city that would become known as a bastion of racial equality under mayor Hubert Humphrey after World War II.

Nor do they convey how Sumner Field ultimately broke down racial barriers. In an encouraging testament to the power of place, Janet Raskin, a daughter of the Jewish North Side, explained how the park served as a commons for all Northsiders. “We had white, we had the park, and we had Afro-American,’ And we all played together in the park.”

For more about the history of Sumner Field and north Minneapolis, click here to watch Cornerstones.

Both maps are from the collections of the Hennepin County Library.