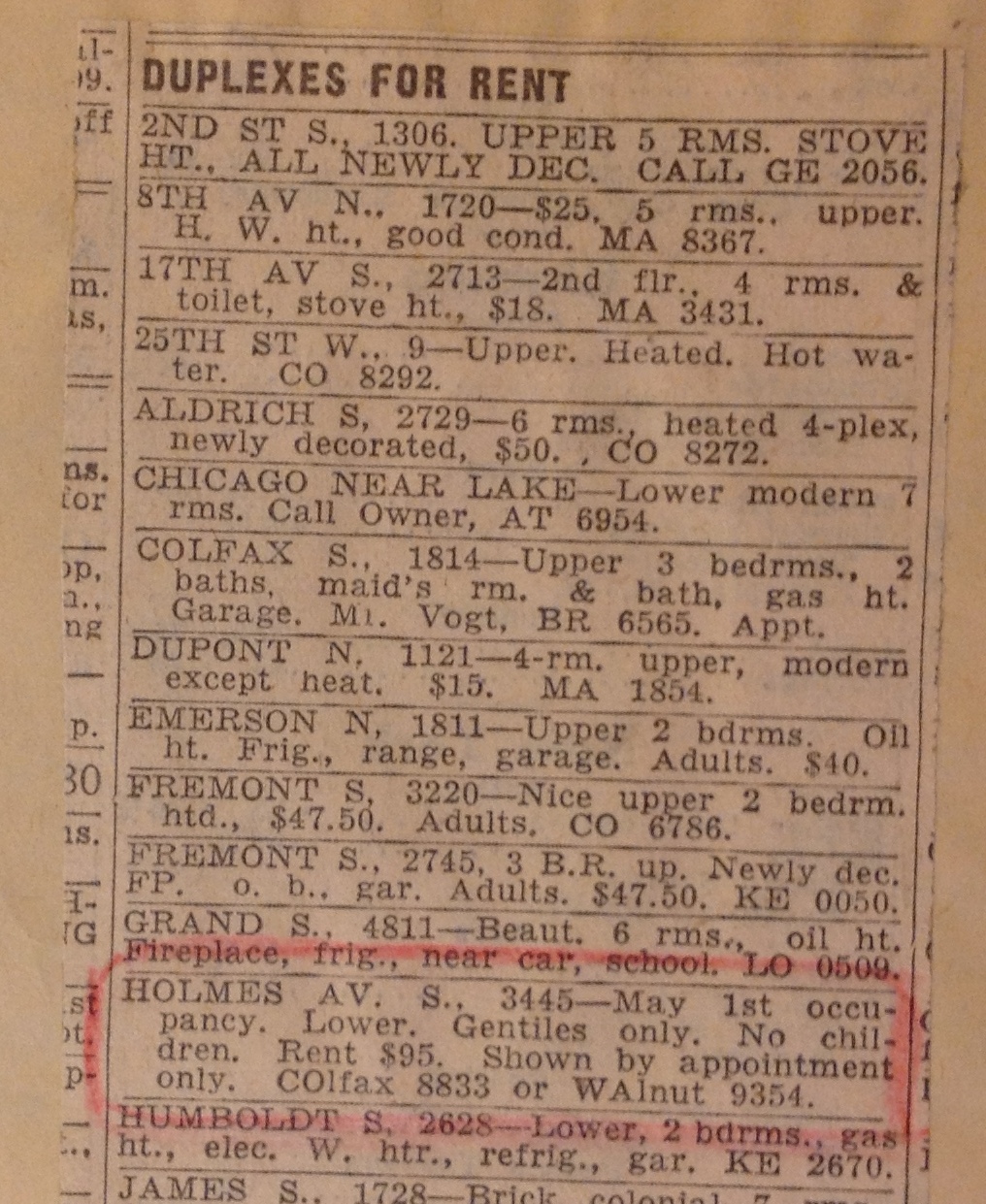

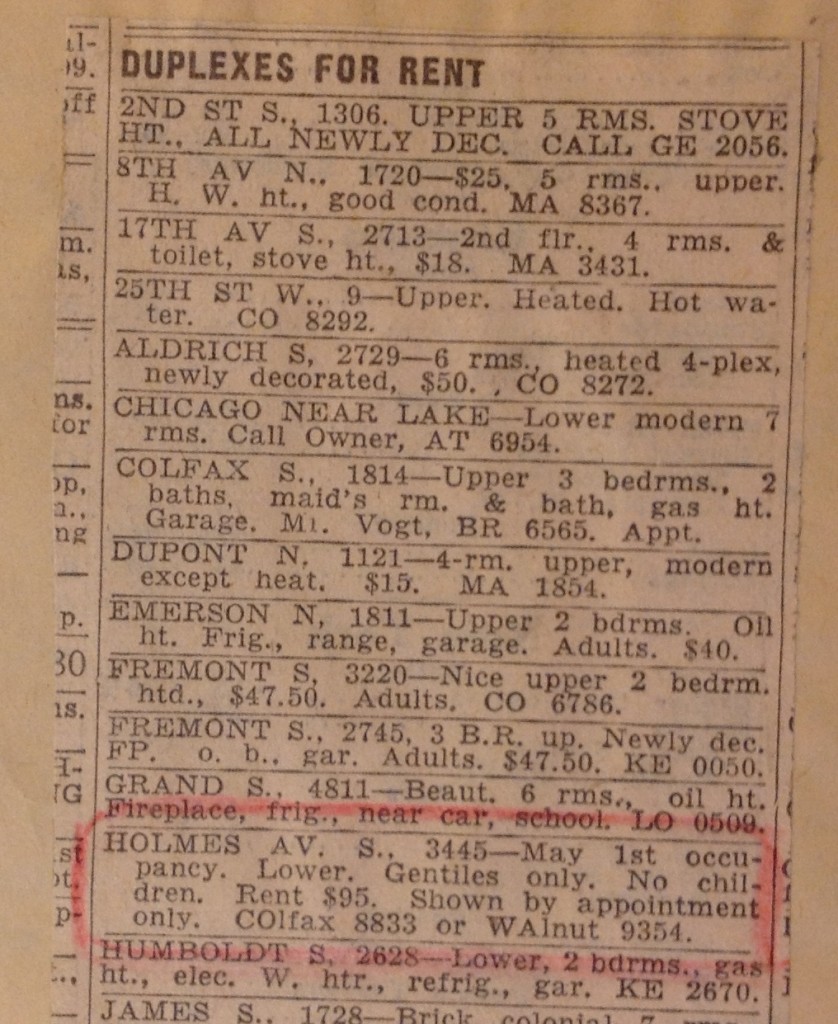

In the spring of 1942, the Minneapolis Morning Tribune published a rental advertisement for a duplex on 34th and Holmes Avenue South. The opportunity to inhabit the elegant Tudor-style building two blocks from Lake Calhoun would have been attractive, especially in light of the wartime housing shortage. At first glance the rental notice seems formulaic: “May 1st occupancy. No children. Rent $95. Shown by appointment only.” Yet one of its provisions jars modern readers: “Gentiles only.”

This advertisement appeared five years before journalist Carey McWilliams named Minneapolis “the capitol of anti-Semitism in the United States.” In 1947, the radical journalist distilled years of commentary on the city into a pithy article in Common Ground that drew on the imagery of totalitarianism made famous by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. “In almost every walk of life,” McWilliams wrote, “‘an iron curtain’ separates Jews from non-Jews in Minneapolis.” McWilliams declared: “Minneapolis is the only city in America in which Jews are, as a matter of practice and custom, ineligible for membership in the service clubs. . .Even the Automobile Club in Minneapolis refuses to accept Jews as members.”

McWilliams’ devastating description rocked the city, helping to spark a community-wide effort to remake race relations in the city during the latter half of the 1940s. But he was hardly the first outside observer to level these kinds of accusations. In 1943–one year after this ad was published–journalist Selden Menefee visited the Mill City while gathering material for a book about the American people during wartime. He was shocked by the city’s hostility to Jews. “Anti-Semitism is stronger here than anywhere I have ever lived,” one professional man told him. “It’s so strong that people of all groups I have met make the most blatant statements against Jews with the calm assumption that they are merely stating facts with which anyone could agree. ”

Commentators speculated on the origins of this prejudice, settling on another set of ethnic stereotypes for explanation. They blamed Scandinavian “clannishness”; Lutheran hostility toward other religions; and Yankee “aloofness.” They singled out the city’s trade unions for racism. They decried the influence of evangelicals like William B. Riley and Luke Rader, who mixed biblical prophecy with anti-Semitic bile.

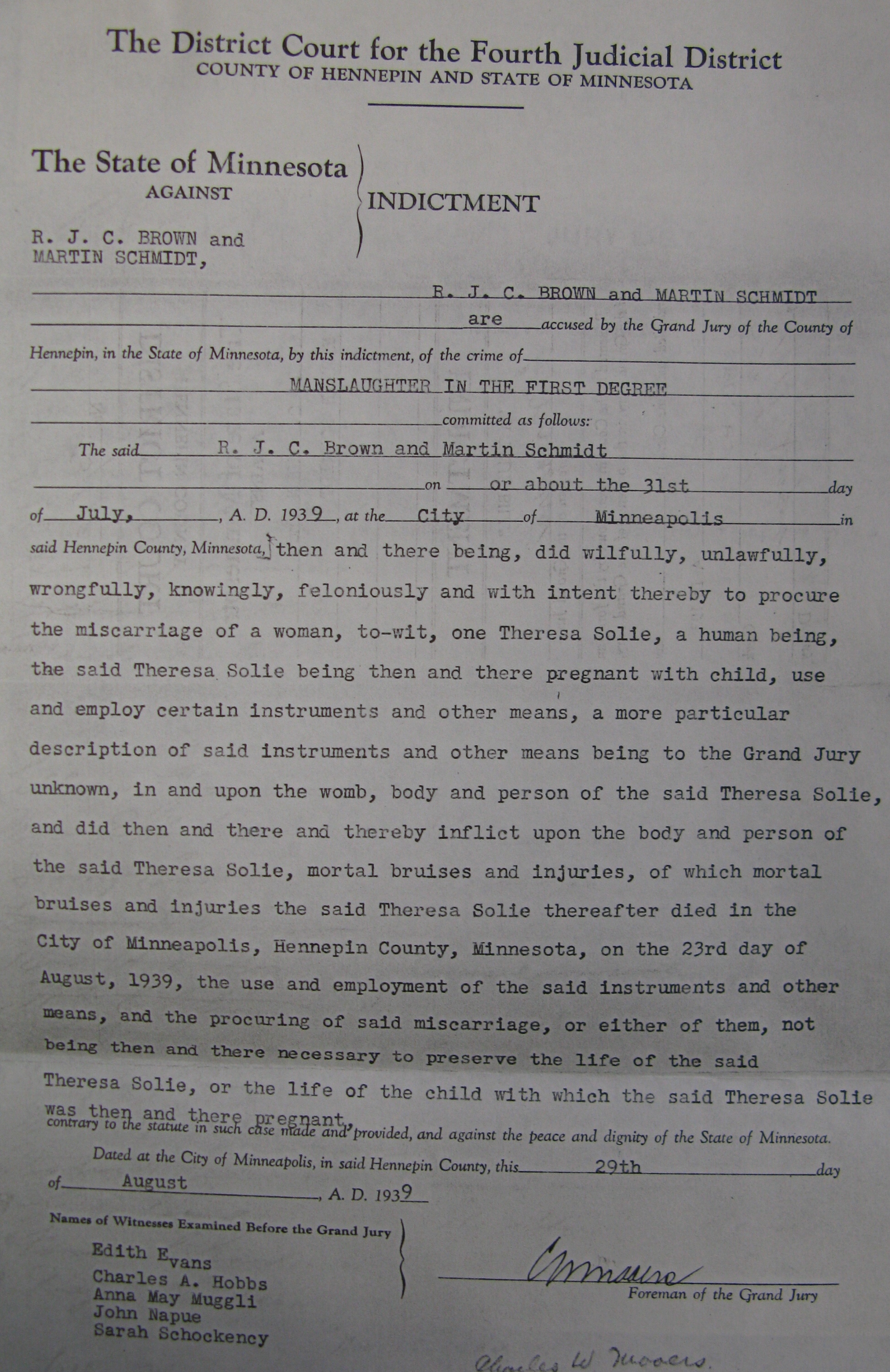

Religious intolerance in the isolated “Gateway to the Northwest” would probably never drawn national attention without the efforts of local Jews, who organized in 1938 to fight a rising tide of anti-Semitism. Jews had long been scapegoats. But the rise of Hitler and anti-Semitic totalitarianism re-cast this rhetoric. In the wake of a bitter election campaign that turned on anti-Semitic propaganda, Mill City Jews concluded that countering these prejudices was a matter of survival.

Out of this resolution grew the Jewish Council of Minnesota, which appointed Samuel Scheiner as its first director. Charged with documenting incidents of anti-Semitism, Scheiner crusaded against bigotry in the community for three decades. He fought many battles on the terrain of property and real estate, where racism was firmly institutionalized.

On April 2, Scheiner typed a shockingly conciliatory protest to John Turber, the owner of the Holmes Avenue property. He opened by acknowledging that the landlord had broken no laws. “The owner of any real estate has the absolute right to select his tenants on the basis of congeniality and ability to get along with other tenants in the building,” Scheiner conceded. But “we believe that where a real estate owner draws the line of discrimination, such feelings should not be expressed by way of an open want-ad, for it serves to stigmatize as socially inferior or undesirable a whole group of American citizens.”

Scheiner allowed that there were ” unworthy Jews and vulgar Jews” and that attempts ” to mix Jewish and non-Jewish tenants sometimes reacts to the detriment of the person owning the property.” But he appealed to Tuber’s patriotism. “We all have a job to do in educating our fellow citizens,” he declared. These practices signify “the beginning of a trend toward totalitarianism, which I am sure you abhor equally as much as we.”

Scheiner closed by acknowledging that Turber might remain determined to “keep people of our faith out of your building.” But he implored him to “exercise your policy of discrimination in a discrete and unpublicized manner. I am sure that you will find many ways to keep from renting your premises to people of our faith without the necessity of advertising the same so openly.”

Scheiner reported that Turner withdrew his advertisement. Perhaps the landlord had secured a tenant who met his criteria. But even if Turner had recanted his prejudice, the retraction of this ad would have been a minor victory in a long-running battle for tolerance.

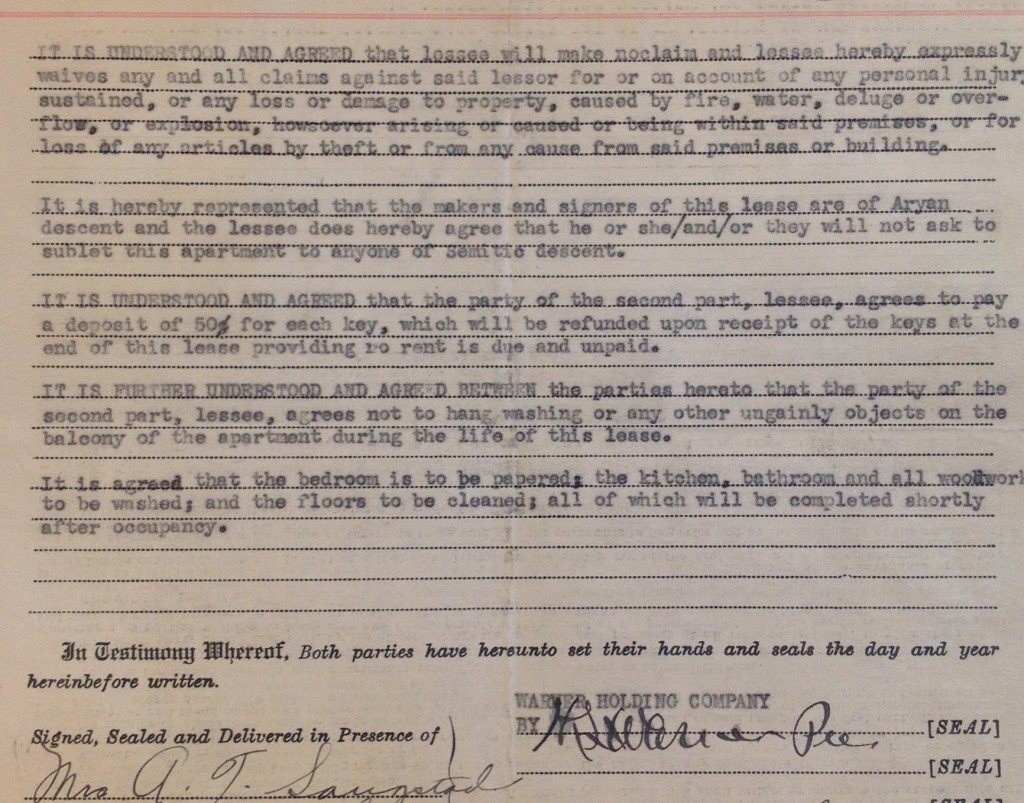

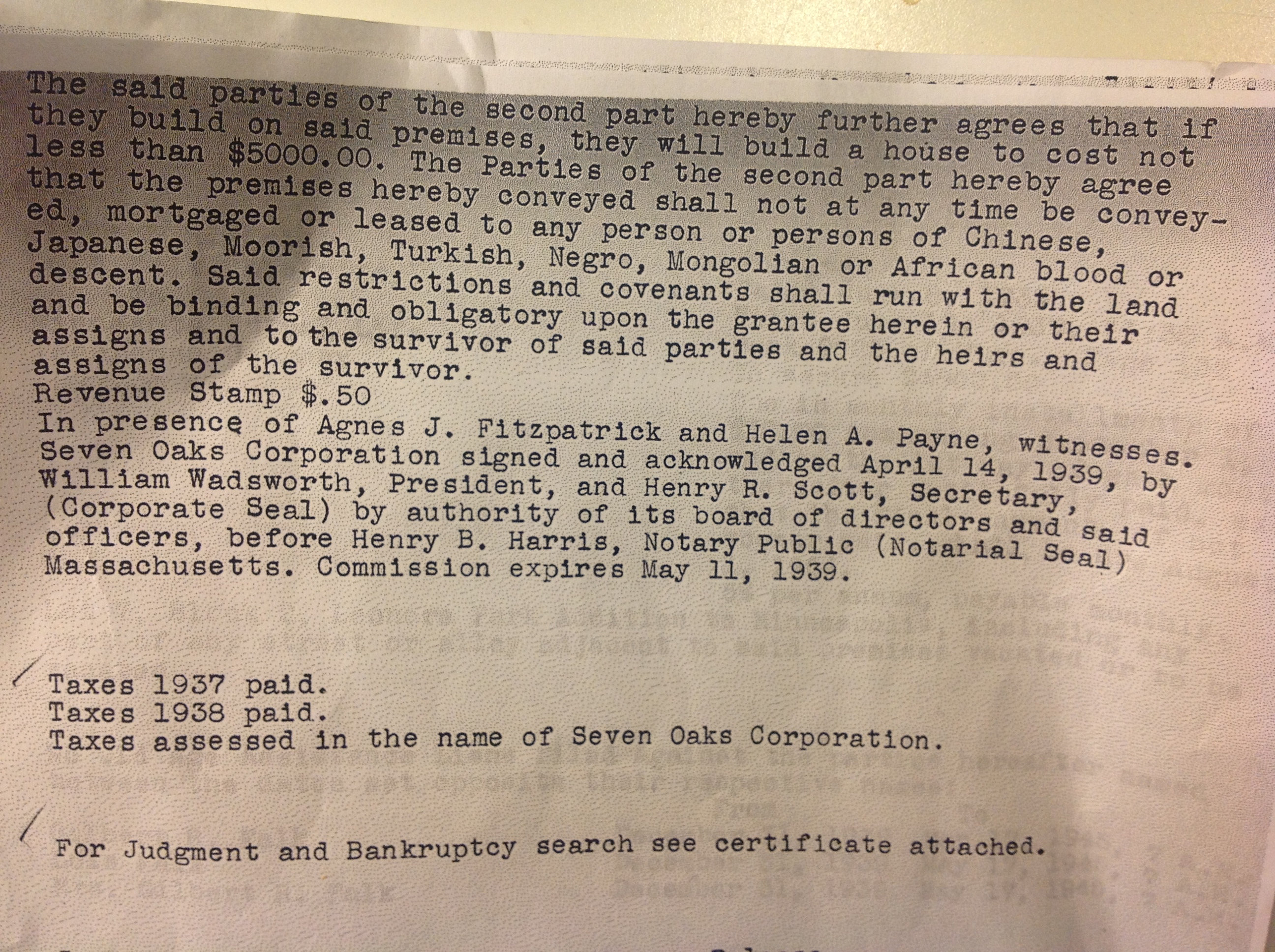

Ads like these were only one weapon in the arsenal of anti-Semites. Jews were barred from living in South Minneapolis by property managers who denied their rental applications; real estate agents who turned away their purchase offers; neighborhood organizers who wrote restrictive covenants into property records; and landlords who penned their prejudices into leases like this one:

This rental agreement for the “Dupont Court” Apartments on 1101 West 28th Street stipulates that the floors will be washed, the bedroom walls papered and a deposit paid for each key. It forbids the tenant from hanging wash from the balcony. And finally, it makes two declarations. First: “the makers and signers of this lease are of Arayan descent.” And second, the tenant was prohibited from subletting “this apartment to anyone of Semitic descent.”

Images and correspondence are from the Council Records of the Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota at the Minnesota Historical Society.