Today’s blogger is Stewart Van Cleve, a graduate student in the program for Library and Information Science at St. Catherine University. The author of Land of 10,000 Loves: A History of Queer Minnesota, Stewart discovered the tower archives at Minneapolis City Hall when he was researching the history of gay sexuality in the city. He has joined forces with Historyapolis to illuminate the holdings of this forgotten cultural repository.

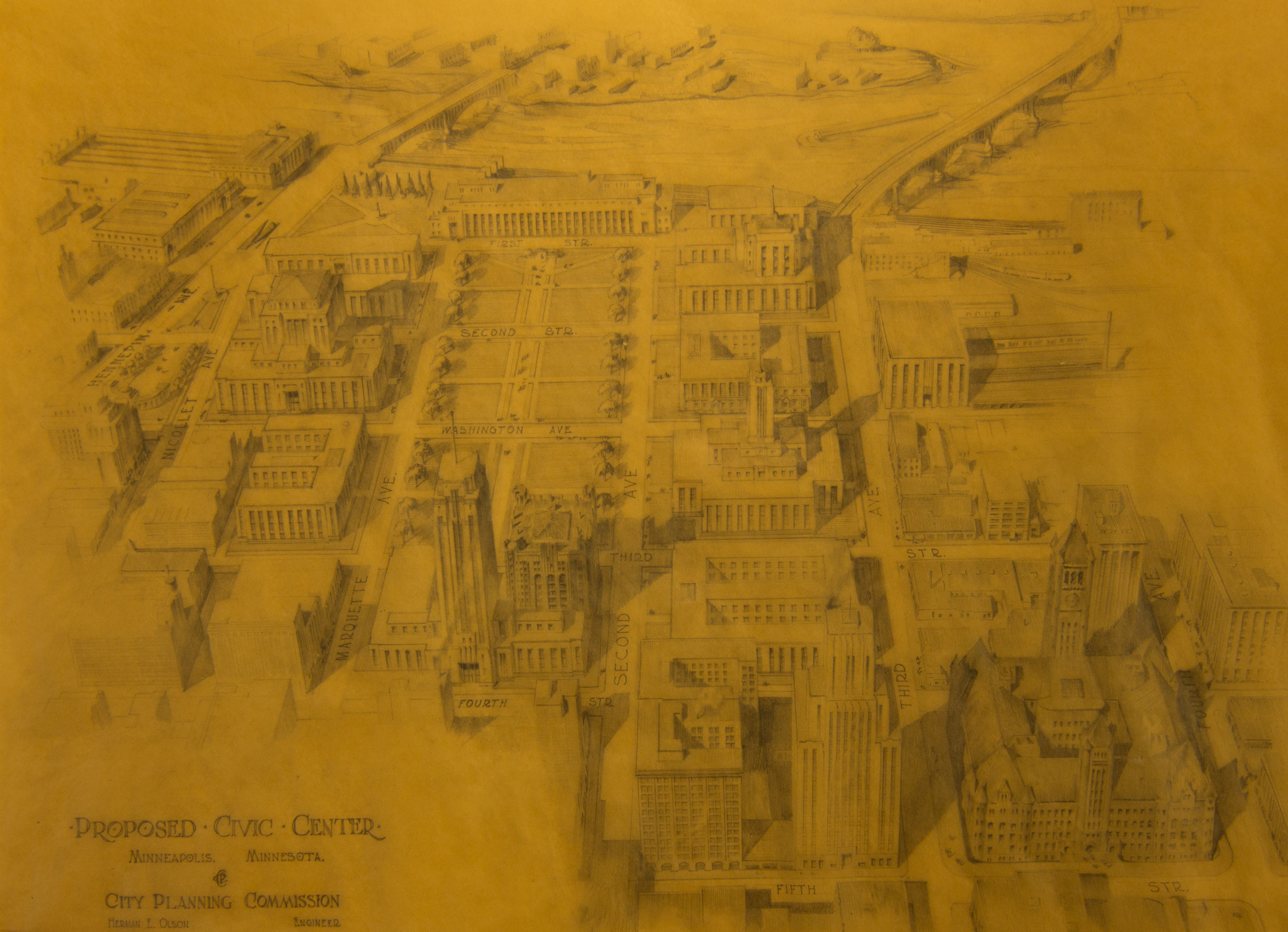

Thirty years before bulldozers descended on the Gateway– flattening forty percent of the city’s downtown–Minneapolis planners imagined transforming this problematic sector of the city. At the depths of the Great Depression–when the Federal Government was funding construction projects meant to restore public faith in capitalism and government–Minneapolis envisioned using some of this money to build a grandiose new “Civic Center” overlooking the Mississippi River.

Other than the main Post Office–which was constructed in 1934 and still dominates the downtown riverfront–little of this vision was realized. Drafted by the Minneapolis Planning Commission, this large plan illustrates the Main Post Office’s role in a broader scheme to replace the region’s largest skid row with a modernistic district of government buildings.

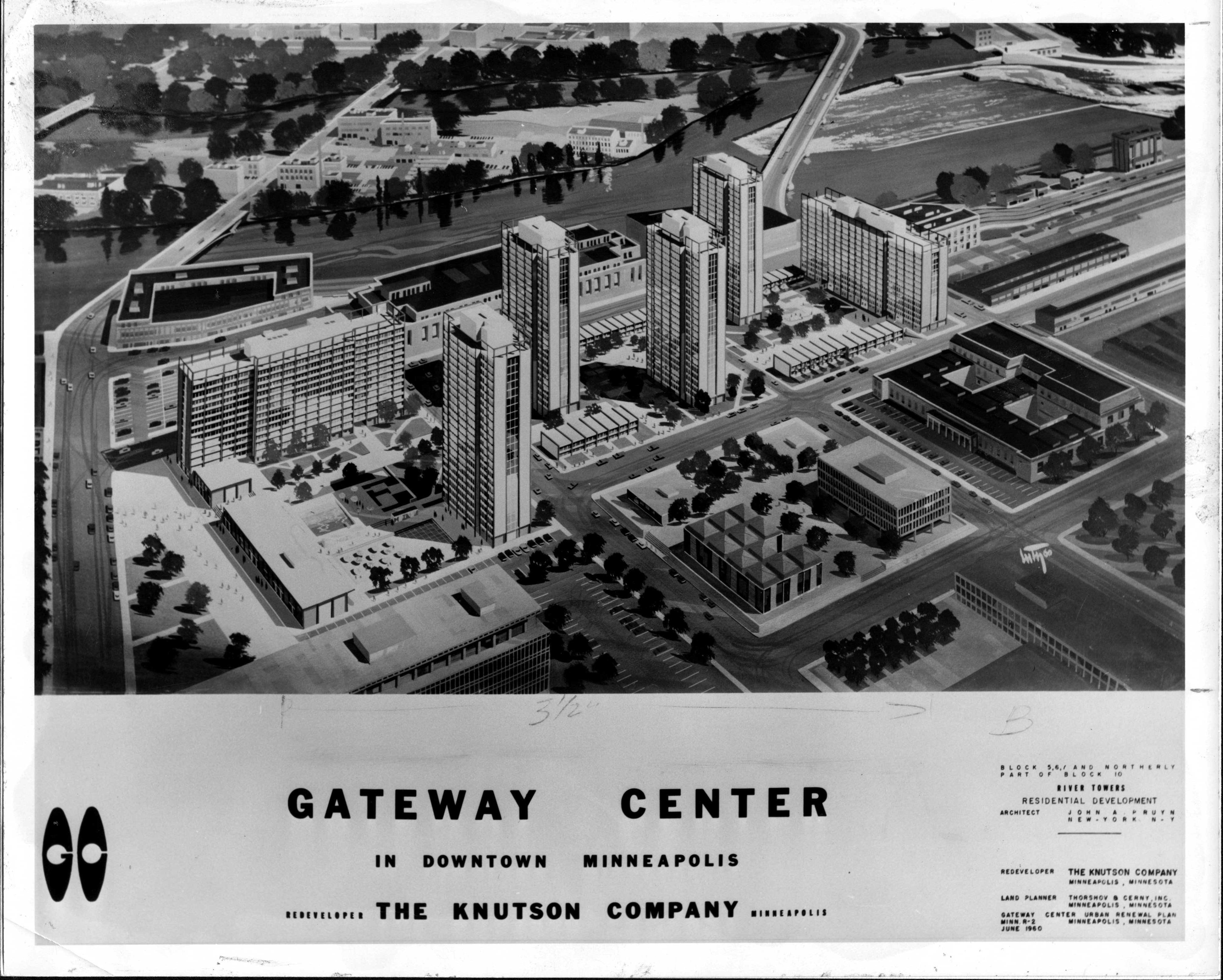

The “Civic Center” plan would have leveled hundreds of buildings, including the Milwaukee Road Depot. This version would have spared the beloved Metropolitan Building, which did not survive the later redevelopment of the area in the 1950s. This renewal effort did spare the Milwaukee Road Depot, which stands today as one of the only remnants of this forgotten district.

The Post Office was to be situated on one end of a large park. Only part of this plaza was ever built and Pioneer Square never became the kind of public space planners envisioned. But the construction of this civic mall allowed the city to demolish what was widely considered a vice-ridden “slum.” The plaza was expected to serve as a parade ground for the National Guard, which had manned the barricades when labor unrest had turned the downtown into a battleground in 1934.

During its brief existence, Pioneer Square featured “The Pioneers,” a sculpture that now sits at Marshall Avenue and Main Street in Northeast Minneapolis. The park disappeared in a later round of redevelopment. The Churchill apartment tower was constructed on the site of the park in 1981.

This long-standing desire for a downtown plaza may be realized this year. On the other side of downtown, the new Vikings’ Stadium will be fronted by an enormous new park reminiscent of Pioneers Square. No one suggests that it may double as a military drilling ground.

At the same time, the main post office has become a topic of conversation among some planners and developers, who eye its walled-off design as outdated and in need of complete renewal. If the building falls to wrecking crews—an unlikely scenario, thanks to its location within the St. Anthony Falls Historic District—it would also fall victim to the very mentality that inspired it: a belief that urban rebirth occurs on the heels of total destruction.

The Civic Center Plan is from the tower archives at Minneapolis City Hall. Thanks for citizen researchers Eric Christenson, Dan Wilhelmsen and Chad Davis for digitizing this and so many other images.