In Minneapolis in 1946, it was virtually impossible to find a place to live. Years of economic depression and war had stalled home construction even as the city’s population continued to swell. And demobilization had escalated the wartime housing shortage into a crisis. The “train stations filled and emptied and filed again…with waves of uniforms, the dark pews in the waiting rooms become home for soldiers and sailors–stretched out asleep or sitting up, sleeping heads hanging, chins on chests,” remembered Hubert Humphrey, who was mayor at the end of World War II.

Under Humphrey’s leadership, the city launched its “Shelter-A-Vet” campaign, calling on citizens to open their spare bedrooms to returning veterans. And it constructed a small colony of Quonset Huts in Northeast Minneapolis.

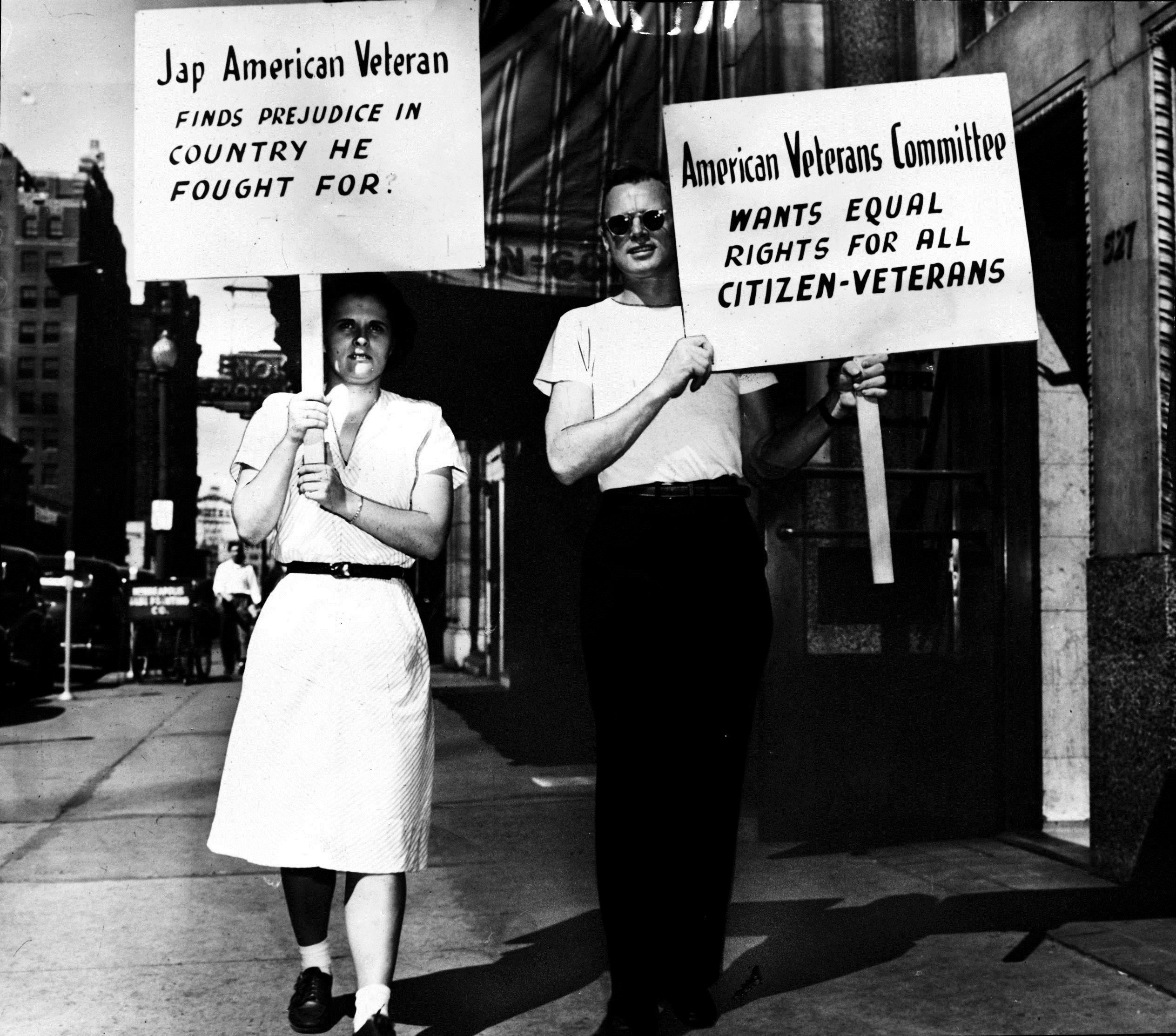

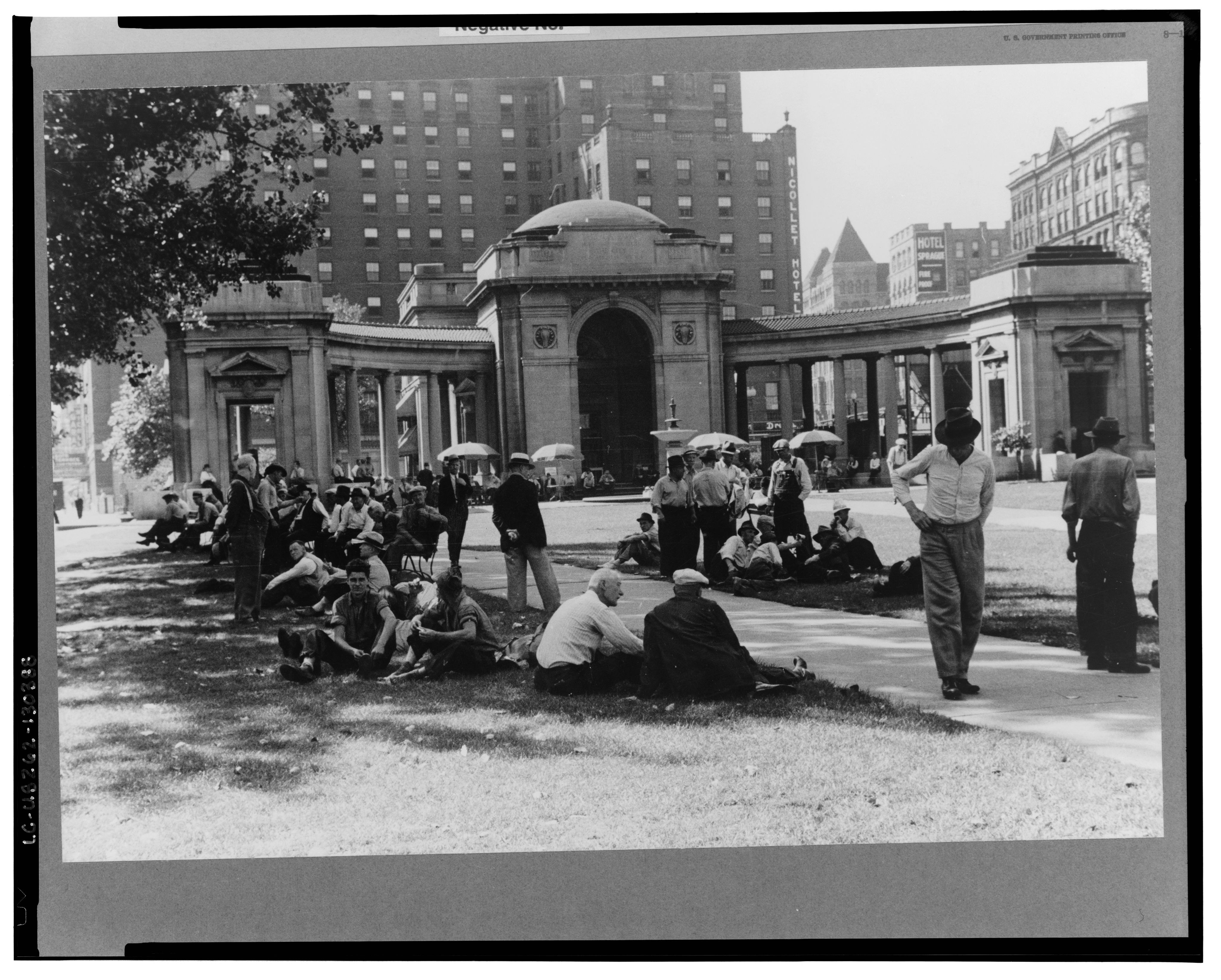

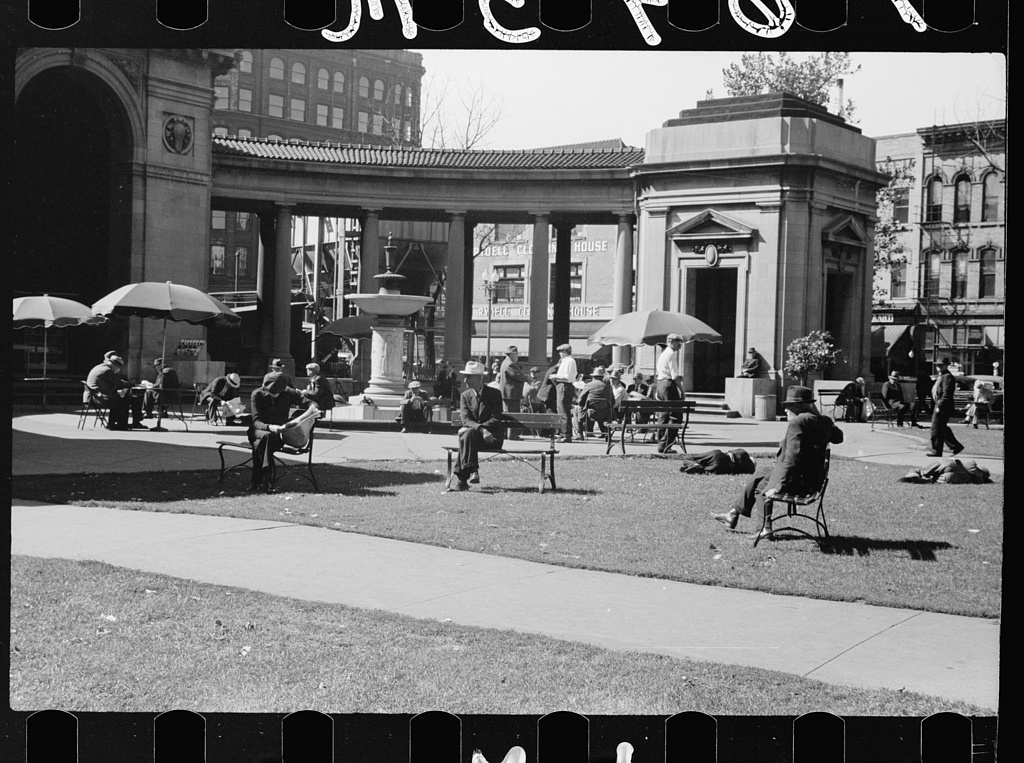

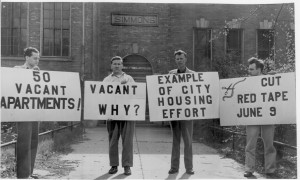

In 1947, the University of Minnesota Veterans Club demonstrated in front of the vacant Simmons School. The group wanted public buildings to be converted into emergency housing. Image is from the Special Collections department of the Hennepin County Central Library.

Veterans did not wait for the city to find them homes. Fifty former soldiers who had enrolled at the University of Minnesota organized Oak Hill Builders to build low-cost homes on a plot of vacant land in Northeast Minneapolis. With the help of local real estate firm Dickinson and Gillespie, they sought to construct affordable homes in close proximity to the University.

One of the veterans who joined this cooperative housing venture was Jon Matsuo. Married and the father of a baby daughter, the American-born veteran got second dibs on a lot in the new subdivision. But when he met with the real estate agent to make his choice, he was told that he could not live in Oak Hill because of his Japanese ancestry.

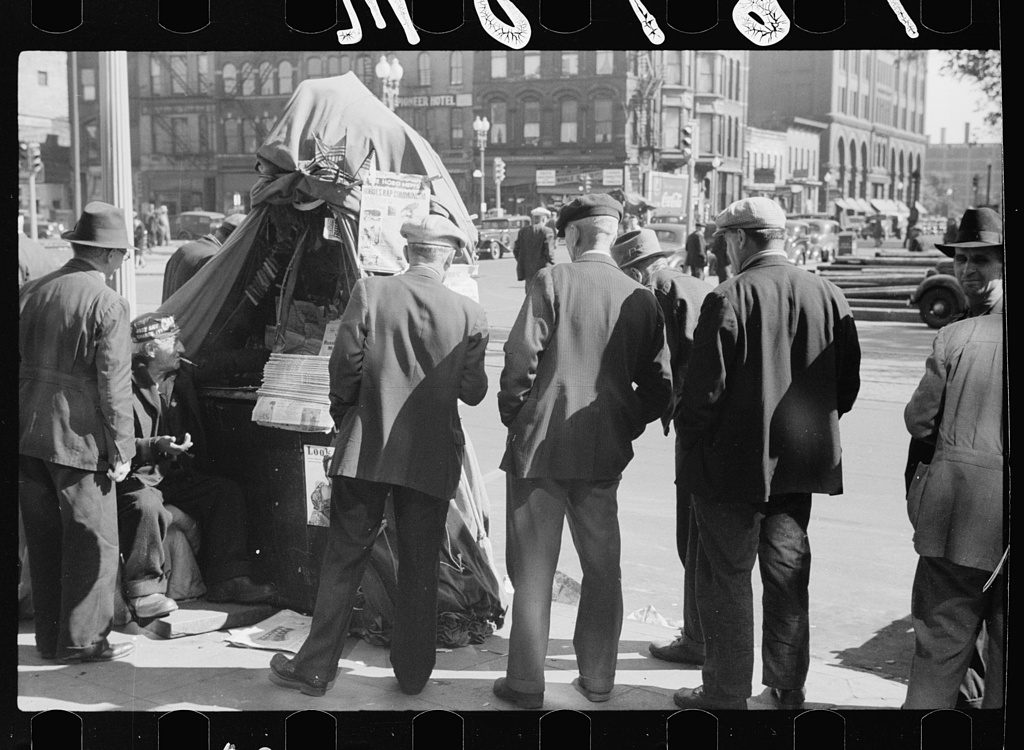

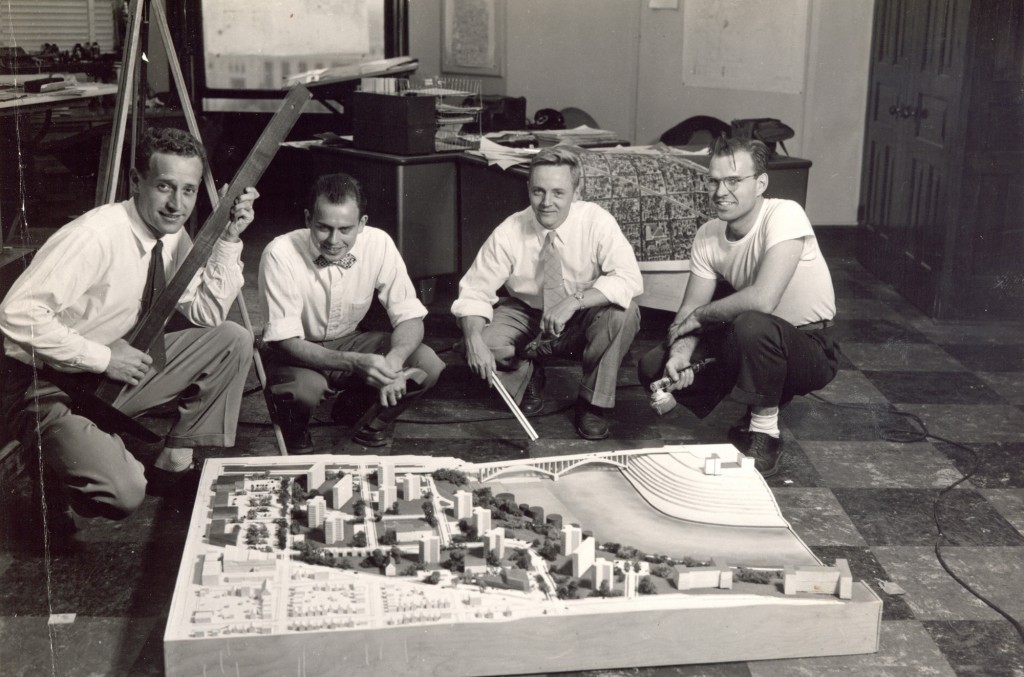

Some white Minneapolitans were outraged when news broke that a veteran had been denied housing. The American Veterans’ Committee–which organized the protest against the Minneapolis Board of Realtors shown above–condemned the practice of using legal clauses to restrict real estate purchases by race as “unnecessary, undemocratic and un-American.” Twenty community organizations ranging from the Communist Party to the Young Women’s Christian Association lined up behind the AVC to challenge Matsuo’s exile from Oak Hill and demand that the city ban the use of restrictive covenants in new developments.

That same year, Minneapolis did change the law to prohibit racial covenants from being used in new developments. And this episode did help to justify the work of the Minneapolis Self-Survey of Human Relations, which employed sociological methods to challenge racial assumptions in the city. This experiment helped to put Minneapolis on the map as a national leader in civil rights; in some circles it eclipsed the ignominy of being called the “capital of Anti-Semitism.”

Jon Matsuo went on to become a community leader, serving as the first president of the United Citizens’ League, the first organization devoted to protecting the interests of the Japanese-American community in Minneapolis.

I wish I knew more about what happened ultimately happened to Matsuo and his family. The story seems to end on a happy note. Newspaper reports say that the family was offered the chance to build a house at the edge of the new subdivision. And their humiliating injustice fueled social change. Outcry changed both attitudes and policies for the better.

But this narrative of racial bias is both longer and less tidy than this initial telling would suggest.

The difficulties faced by the Matsuos were hardly unique. Most Asian Americans, Native Americans, Jews and African Americans faced significant barriers when they sought to rent or buy a home in Minneapolis in the first half of the twentieth century.

Take the case of Daisuke Kitagawa, a Japanese minister who had been sent to Minneapolis in 1944 to care for the growing Japanese community affiliated with the World War II language school at Fort Snelling. He thought his family’s grueling search for housing was over when they found a “tiny three-room house at the north end of Minneapolis.” But then “the telephone rang, and the man who had just rented us the house informed me that he changed his mind because there was opposition from neighbors.” It was only with intervention from the Episcopal Bishop of Minnesota that the man relented in the face of “unbearable” opposition.

Though these types of prejudicial attitudes were difficult to overcome, legal and financial hurdles posed even greater challenges to prospective renters and home buyers. Real estate covenants like the one that kept Matsuo out of Oak Hill were used for decades in Minneapolis. Before World War II, they were employed largely to keep African-Americans from buying homes in white neighborhoods. By 1948, a survey of realtors revealed that 40 percent of new developments in Minneapolis were covered by this type of restriction. But the hundreds of cases involving African Americans never generated the kind of protest that greeted the injustice faced by the Japanese-American student.

Real estate leaders defended these measures as economically practical. “For such extensive financing as is required for this project, the federally backed savings and loan associations and banks require such a clause,” Elliot Gillespie, president of Dickinson and Gillespie told the newspaper. “Also, a large segment of the public will not buy homes in real estate developments which do not include the restrictive racial clause.”

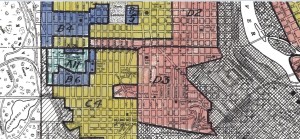

According to this logic, property values rested on racial segregation; residential race-mixing brought instability and risk to investors. These assumptions were codified in federal lending practices that were developed during the Great Depression. In 1934, the Federal Housing Administration created a system for rating the risk involved in different properties. And race was central to this scheme. Properties in white neighborhoods were deemed safe investments; those in African-American neighborhoods did not qualify for any federally-backed funds. African-Americans could not buy homes in white neighborhoods. But they also could not get financing for homes in African American neighborhoods.

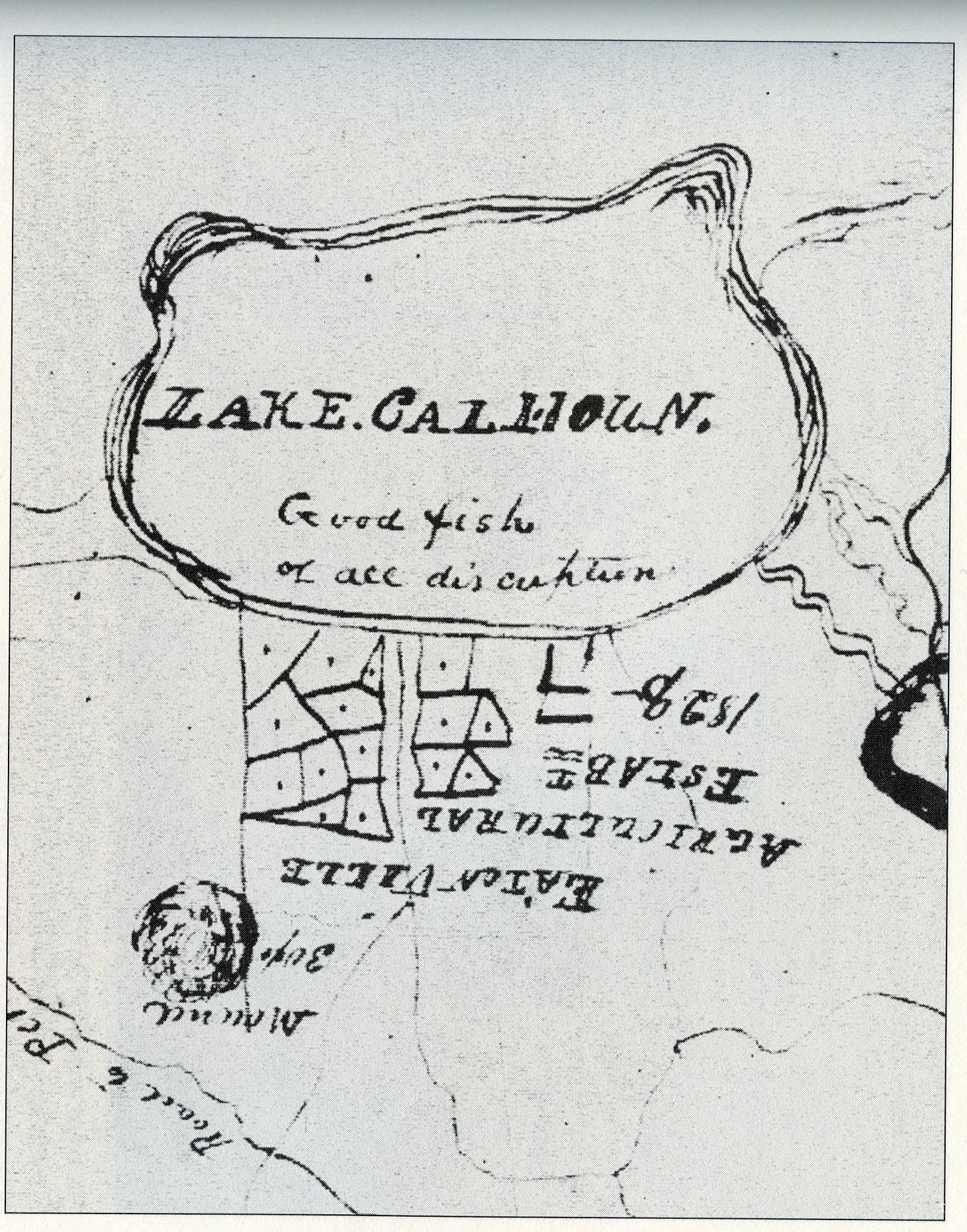

This is a detailed segment of one of the “risk” maps developed by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation during the 1930s. This map shows the near north side of Minneapolis. The areas shaded red were deemed too hazardous for federally-back loans. Most of the city’s African Americans lived in these areas that were “red-lined.” Map is from the National Archives and Records Administration via the Mapping Inequality Project.

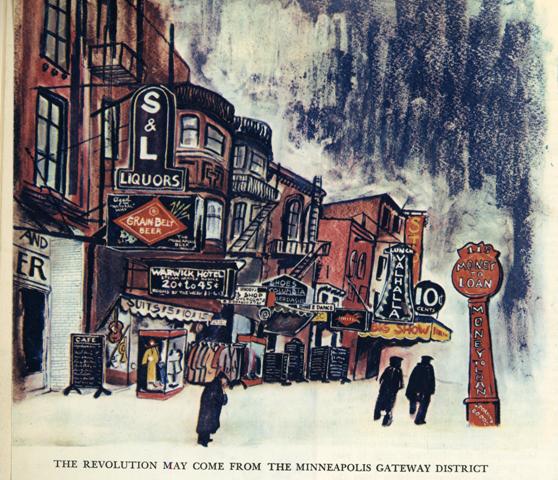

The system demanded that realtors serve as the border patrol, monitoring the lines that divided neighborhoods by race. A professional code of ethics actually prohibited anyone associated with the national association of realtors from selling houses in white neighborhoods to people deemed not white (a broad swath of humanity that covered persons of “Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro , Mongolian or African blood”).

When Matsuo’s story became public, most realtors saw no reason to relax their vigilance. The protesters associated with the American Veterans’ Committee, according to real estate developer Gillespie, were “a bunch of trouble-making, flag-waving communists.” The actions of one firm, he asserted, could not change the situation. The protesters “will have to go to the real estate board, savings and loan associations, bankers associations and get an amendment in the federal constitution if they hope to abolish use of the restrictive covenants.”

Gillespie’s red-baiting of the civil rights protesters sounds bigoted and paranoid to modern readers. But his warning was correct, in some ways. It would take more than one real estate firm or even one city to change the entrenched policies that buttressed residential segregation in the United States for most of the twentieth century.

The same federal lending programs that made homeownership possible for millions of Americans created new barriers for African Americans to become property owners. Today we are still living with this legacy. Many of our modern day inequalities have their roots in these structures that were born of fear in American cities a century ago.

Sources for this post: Daisuke KItagawa, Issei and Nisei: The Internment Years (New York: Seabury Press, 1967): 165-66; Report and Recommendations of the Real Estate and Housing Committee of the Minneapolis Community Self-Survey of Human Relations, Planning Department Office Files, Municipal archives, Minneapolis City Hall; Clipping file for Jon Matsuo and Oak Hill Subdivision, Special Collections Department, Hennepin County Central Library. Special thanks to Rita Yeada, citizen researcher, for finding the sources necessary for this post. Both photographs are from the Special Collections Department of the Hennepin County Central Library.