Today’s blogger is Kevin Ehrman-Solberg, Historyapolis intern.

This weekend, Twin Cities Pride will celebrate the myriad aspects of GLBT life in Minneapolis, which revels in its designation as the “gayest city” in the United States. Pride began as a subdued picnic in Loring Park in 1972 and most people see this quiet gathering as the beginning of a new era of openness for gays and lesbians in the city. It took more than a picnic, however, for queer Minnesotans to win the social, political, and sexual rights they enjoy today.

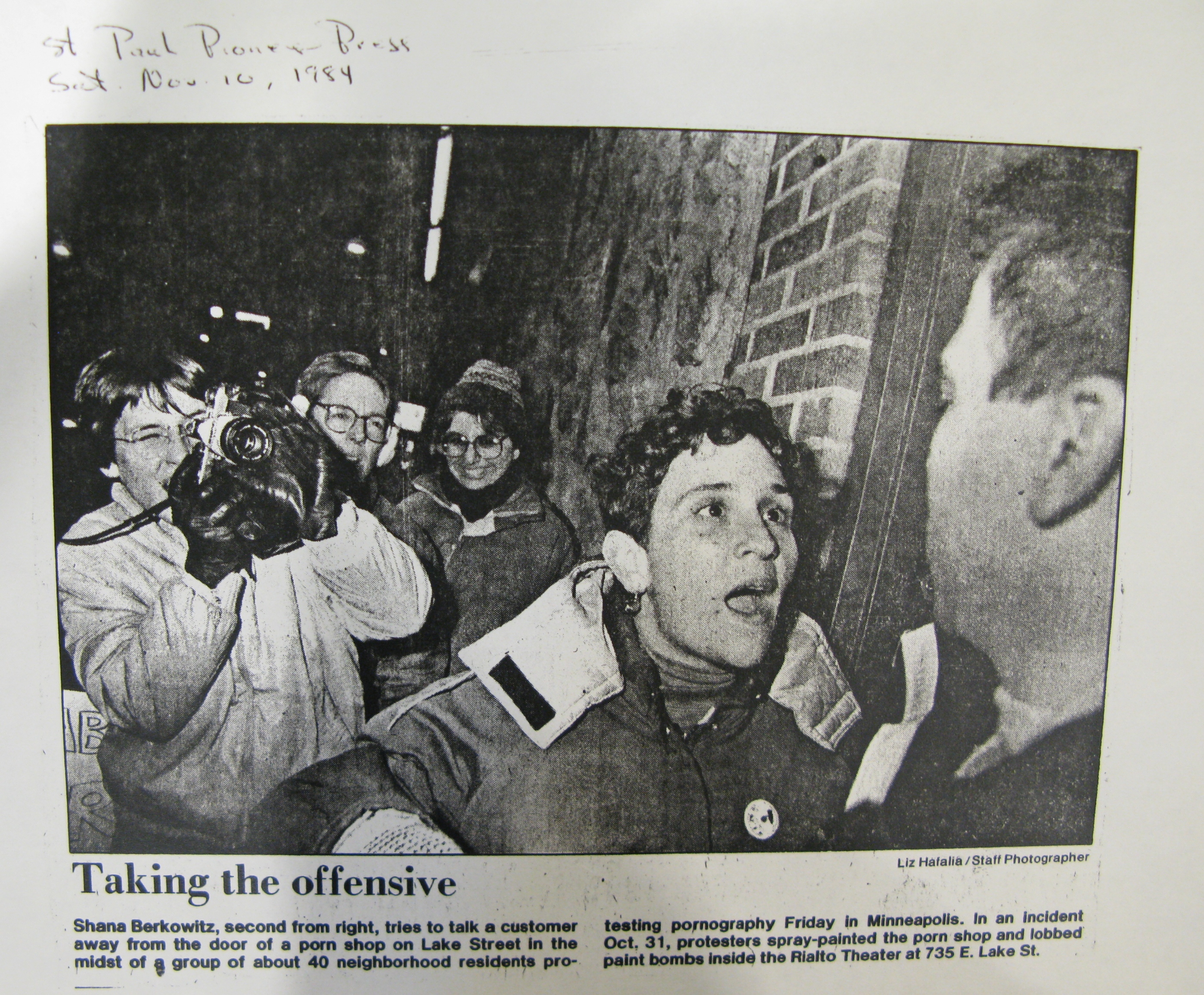

The struggle for these rights took place in a wide variety of community institutions. But a critical–and often overlooked–battleground for sexual freedom in Minneapolis was the city’s adult bookstores and movie theaters. From 1979 to 1985, the city’s growing adult entertainment industry was the site of intense conflict over the rights of gay men to seek sexual partners in public spaces. A critical turning point for gay rights in the city, this “battle of the bookstores” inspired queer Minneapolitans to seek real political influence in City Hall.

In 1979, police launched a crackdown against the city’s growing pornography industry. They were under intense pressure from neighborhood activists, who objected to the proliferation of pornographic bookstores and movie theaters in South Minneapolis. The ensuing police campaign targeted gay men who used adult bookstores and theaters as sites for sexual encounters. Men in Minneapolis, many of them unwilling to self-identify as gay, had been using those spaces since the early 1970s as a way to engage in sexual contact without fear of physical violence or discovery.

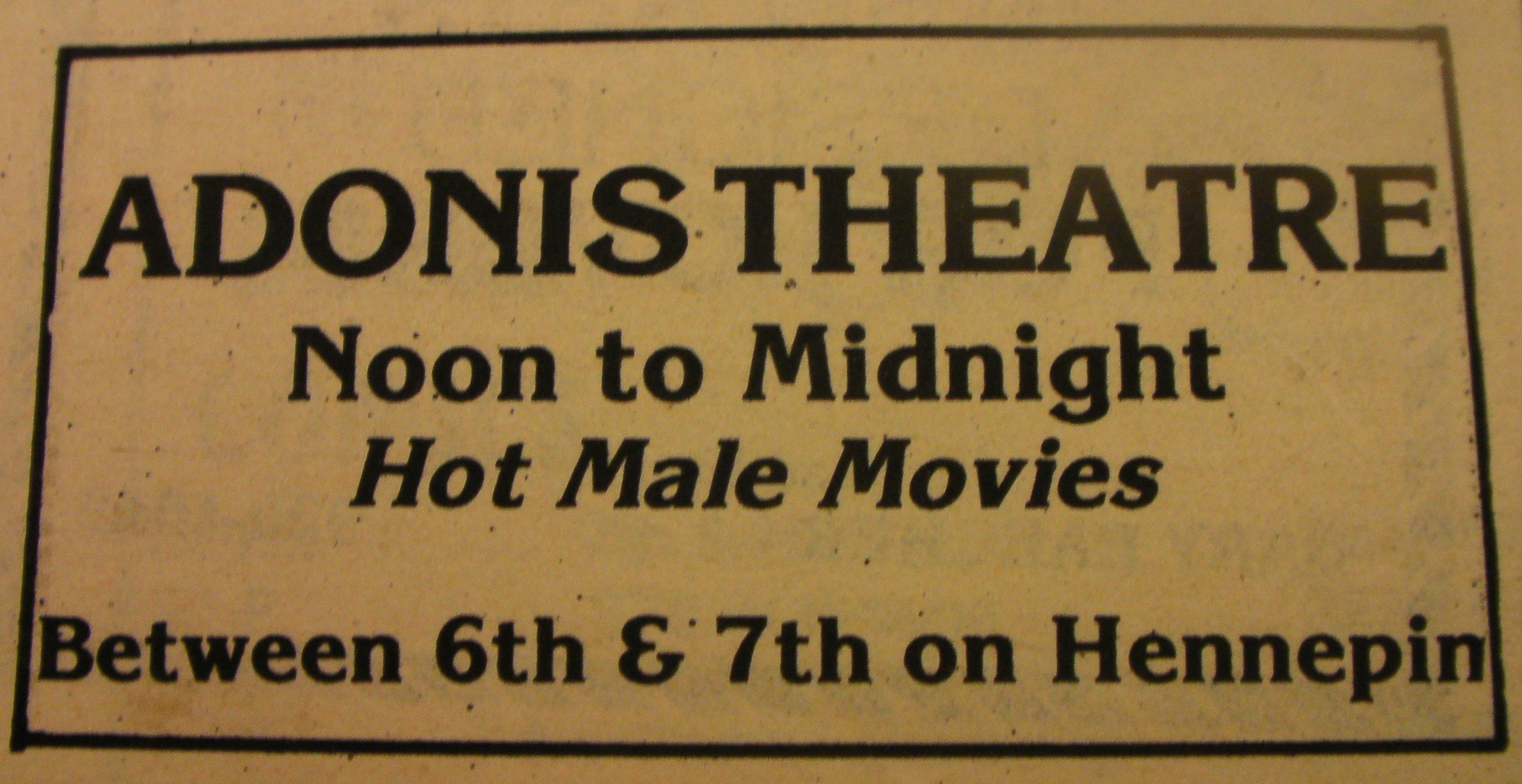

The experience of Mark Weintrob was typical. On August 17, 1982, Mark Weintrob left work and headed to the Adonis Bookstore downtown. He went up to the second floor where a small theater advertised “Hot Male Movies” from “Noon to Midnight.” After taking a seat, he noticed a man staring at him in the dim lights. The two men proceeded to engage in the “normal gay male cruising rituals” until the stranger finally took the initiative and asked Wientrob if he would like to “go somewhere a little more private.” Wientrob followed him to a small boiler room. There, the stranger asked: “Are you a cop?” Wientrob responded with a simple: “No.” “Well I am,” the stranger said, “and you’re under arrest.”

Wientrob became the first man to challenge such an arrest in court. He won, but very few of the men arrested for indecent conduct–a charge used almost exclusively for observed sexual conduct between consenting men–were willing to fight such a charge. Doing so meant public exposure, the very thing these men were trying to avoid.

That exposure could have dire–even fatal–consequences, as the case of the Reverend James Santo illustrates. On December 14, 1982, Santo went into the basement of his Hopkins church and lit himself on fire. His death, and the subsequent investigation, made the front page of the Star and Tribune. “The fire,” the story reads, “which police said may have been caused by Santo pouring gasoline on himself, was preceded 12 hours earlier by his arrest on indecent conduct charges in an adult-oriented bookstore in Minneapolis.” That line is the only mention of the indecent conduct arrest in the Star and Tribune coverage, but it hints at a problem that had been wracking the local gay community for years. Attorney Ken Keate, who regularly represented bookstore arrestees, reported that “about five percent of my calls on these cases are suicide calls.”

The undercover operations of the vice squad netted over 5,000 arrests for indecent conduct between 1979 and 1985. The vast majority of those arrests were gay men. In addition to the shame of such an arrest, many had to endure police brutality when taken into custody. Activists began to mobilize against this harassment in 1979. But they made little headway until 1985, when a coalition of openly gay politicians and community members were able to force police to scale back their entrapment operations. The political muscle exercised by newly elected gay politicians Brian Coyle, Allan Speer, and Karen Clark, signaled a profound change in the dynamics of the local gay community. The Star Tribune, which had all but ignored the bookstore arrests, suddenly took notice. The paper remarked that the police department’s decision to end vice squad entrapment demonstrated a “broad and well-entrenched political base of support for gays” and was one of the first tangible signs of “growing gay political power.”