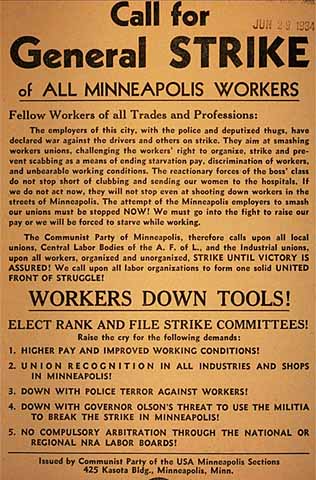

Minneapolis usually imagines itself at play in July, when long, warm days invite us to enjoy our beloved parks and lakes. Yet throughout the twentieth century, July was a time of bitter conflict. In 1967, it brought urban unrest on Plymouth Avenue; in 1934, the Truckers’ Strike; and in 1931, the siege of the Lee family home.

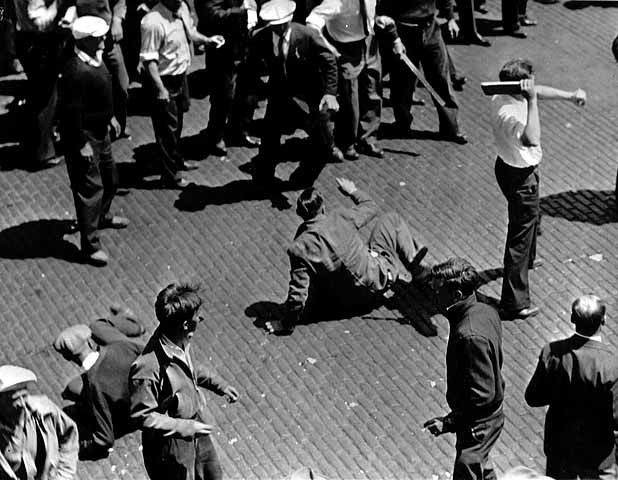

This mob attack in July 1931 was the ugliest racial clash in the city’s history. Edith and Arthur Lee bought a small bungalow on the corner of 46th and Columbus Avenue South. The neighborhood exploded in rage.

The new property owners were African American. The neighborhood was all white.

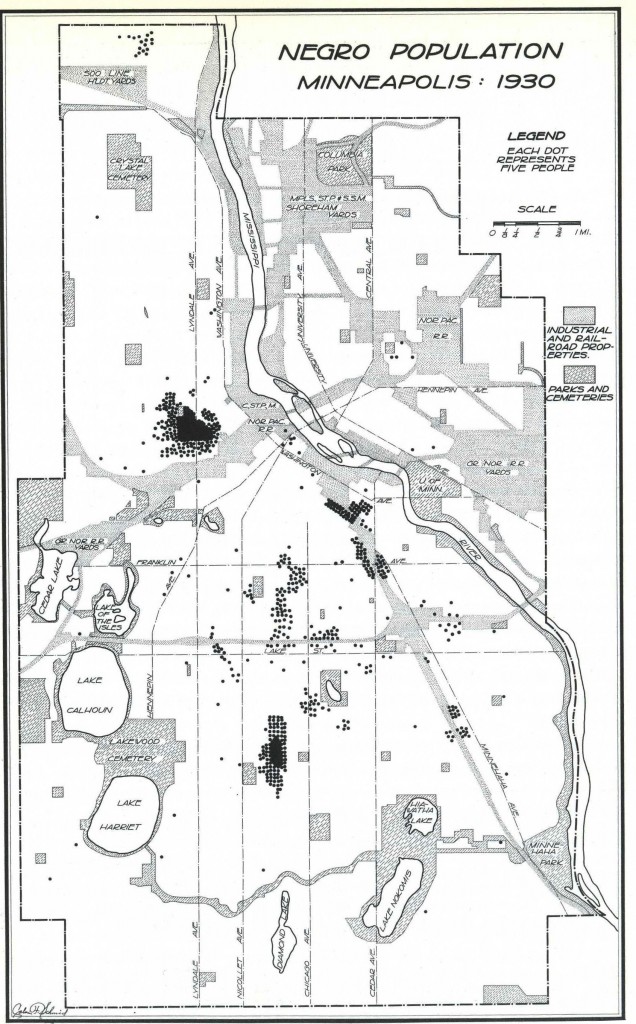

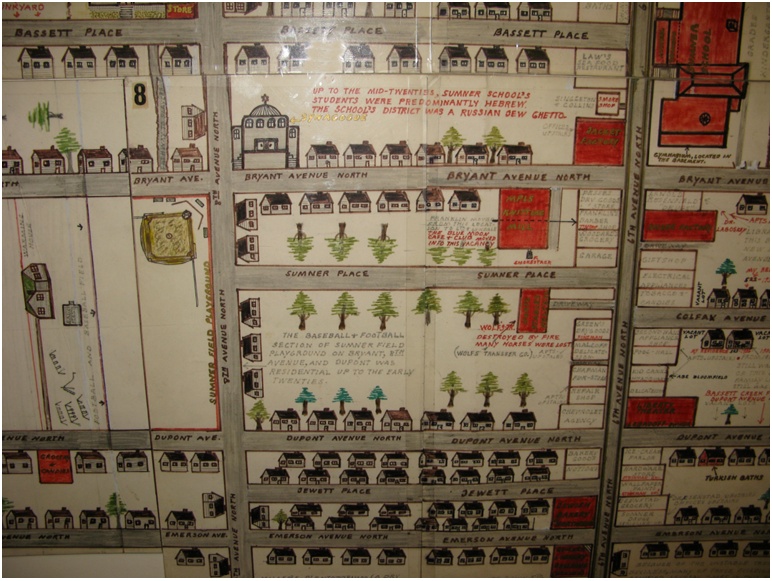

The absence of black residents was no accident. This map shows the concentration of “Negro Population” in Minneapolis, circa 1930. It is one of hundreds of maps created by demographer Calvin Schmid to illuminate the urban landscape of the Twin Cities during the Great Depression. His findings were published in a 1937 opus called the Social Saga of Two Cities, which modern Minneapolitans often mistake for an official city planning document. Schmid’s maps did not designate sections of the city for different groups. His cartography was descriptive, an early effort at what we now call data visualization. He recorded– with offensive labels and pejorative terms–the residential segregation already in place.

The story of the Lee family–and the obstacles they encountered in their quest for home ownership–illuminates how the segregation recorded by Schmid took shape.

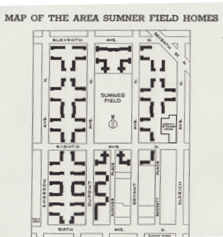

Before the Lee family bought their home, neighborhood activism had purged the blocks around 46th and Columbus of non-white denizens. In 1927, residents had formed the Eugene Field Neighborhood Association. Under the auspices of this group, one hundred residents had signed a voluntary “gentleman’s agreement” that barred them from selling or renting their property to anyone who was “not of the Caucasian race.” Starting in 1930, members of this group had bought homes owned by African Americans in the hopes of making this corner of the city an all-white “restricted district.”

When news came out that a homeowner had decided to settle a grudge with his neighbors by selling his property to an African American, residents mobilized. First they offered to buy the property from the Lees. They promised ever-larger sums to the postal clerk and his wife, pledging to pay thousands of dollars more than the purchase price of the house if the couple would leave the neighborhood. When these offers were rebuffed, they decided to make life unpleasant for their new neighbors. They threw garbage and “refuse of a more unpleasant form” on the lawn. They hurled black paint on the house and garage. They staked threatening signs in front of the house: “We don’t want niggers here” and “No niggers allowed in this neighborhood–this means you.” After dark the family was visited by roving gangs, which yelled epithets and threw stones, bricks and firecrackers. One night, someone killed the family dog.

Arthur Lee was defiant. For the previous twenty years in Minneapolis–as the black community had grown in the city–neighbors in Prospect Park, Kingfield and Linden Hills had used identical tactics to drive African-American property owners out of white sections of the city. And this new homeowner had more resources than most to withstand the pressure of racist neighbors.

Lee had the strength of his convictions. A veteran of World War I, he felt his military service should ensure he would enjoy the rights of full citizenship, regardless of race. “Nobody asked me to move out when I was in France fighting in mud and water for this country,” he declared. “I came out here to make this house my home. I have a right to establish a home!”

Lee also had an unusual degree of economic security thanks to his status as a federal employee; he drew a steady paycheck from the U.S. Postal Service at a time when the Great Depression had thrown one-third of the city out of work. Unemployment in the African-American community was even higher.

Yet the opposition of Lee’s new neighbors proved hard to overcome. On July 9th they declared their determination to restore the racial purity of the neighborhood, phoning Lee to give notice that 500 people would storm his house. Lee summoned the police, which ignored his plea for help. He then turned to fellow veterans at his American Legion post, who organized an armed vigil to protect the family.

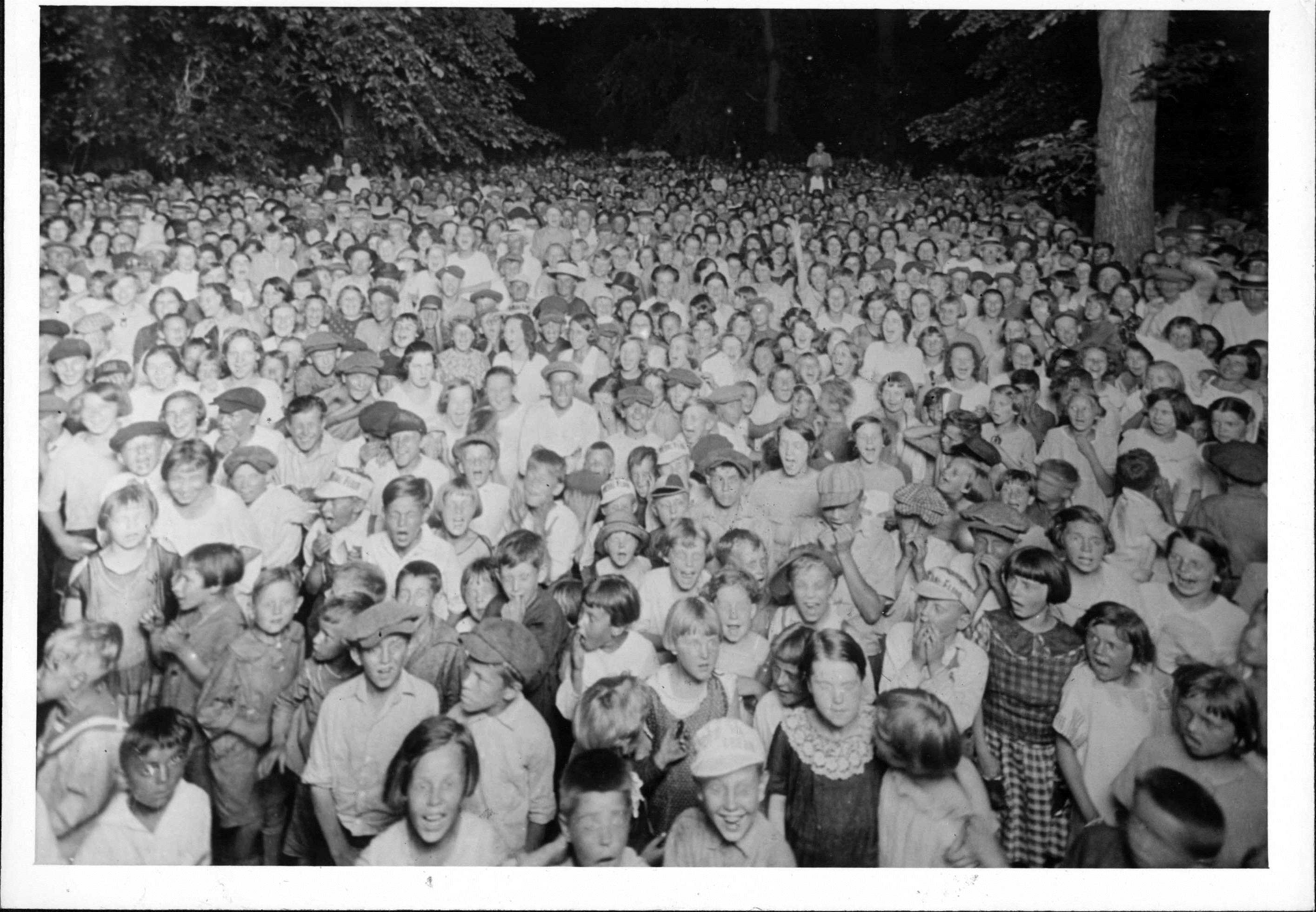

The veterans held the crowd at bay. But over the days that followed, the mob outside the house continued to grow, doubling in size after news of the conflict was reported in the Minneapolis Tribune on July 15th and 16th. One eyewitness recalled how spectators traveled from around the state to witness the siege:

I have never seen anything like it. Here were literally five or six thousand people, men, women and children, both on the curbs and sidewalks, just standing and waiting as near as they could get to this little, dark house. . .Six thousand white people, waiting to see that house burned.

After a speaker at nearby Field School called on the crowd to exhibit “sanity and patience” as well as respect for “principles of human and property rights,” listeners walked out in protest. They swelled the mob outside of the house, where pushcart vendors were reaping the profits of prejudice, supplying refreshments to the horde. But the crowd wanted to do more than eat and drink. Some practiced marching in military formation, in preparation to storm the house; others threw stones; still others demanded immediate action, shouting “Let’s rush the door” and “Let’s drag the niggers out.”

“Inch by inch, the crowd moved close to the home, muttering threats,” according to one of the witnesses. Their encroachment was watched from inside the darkened house. Behind the barricaded door and windows sat a phalanx of African-American veterans and an arsenal of weapons. The Legionnaires had Lugers, Colts, rifles and shotguns at the ready; they had already declared their intention to use their military training to protect the little family.

Mayor William Anderson ordered a police cordon to placed around the house; he issued pleas for calm, even interrupting a band concert at Lake Harriet to instruct citizens to stay away from the clash on Columbus Avenue. A group of citizens worked to broker a “compromise,” by which they meant an agreement to have the Lees leave their house. But with the backing of the NAACP, led by a militant lawyer named Lena Olive Smith, the Lee family remained in their little bungalow until 1933. But they were never accepted into the community they had sought to open up for African Americans.

In the aftermath of the crisis, some white residents were bitter about what they saw as their mistreatment at the hands of the mayor and police, blaming the Lees for the violence. “You know if there was any legal way of keeping a negro out of a white district and ruining the value of everybody’s property for miles around, this disturbance would never have arisen,” a disgruntled Minneapolitan declared in an anonymous letter to a public official. “You know when you hurt a man’s pocket-book, that is something that is never forgotten. . .They talk about justice for the negro, how about a little justice for the white man who has put his life savings into a home.”

Despite the sentiments of this citizen, the attack on the Lee home was largely forgotten after the departure of the family. In the 1940s, memories of this attack were eclipsed by efforts to create a climate of racial tolerance in Minneapolis, which became nationally acclaimed for its embrace of civil rights.

But sociological studies and municipal anti-discrimination laws did little to loosen the rigid residential segregation that had taken shape in the city in the early part of the twentieth century. This meant that the neighborhood was still all-white thirty years after this episode, when another African-American family decided they wanted to live near Minnehaha Creek. This family was greeted with angry glares and “For Sale” signs in neighboring yards. But no angry mob took shape. And they were not subjected to the terror of arson and bombings experienced by “blockbusters” in Chicago and Detroit. “Minneapolis,” journalist Michele Norris declared in her autobiography, which described her childhood in the neighborhood that drove out the Lees, was “known for tolerance.”

In recent years, a new generation of neighborhood activists have grappled with this ugly legacy, illuminating a difficult history that shows that Minneapolis was not always renowned for tolerance. They have commemorated the disturbing events of July 1931 and placed a plaque outside the Lee family home. The house itself was recently put on the National Register of Historic Places, thanks to a group of activist-researchers who have worked to recover the details of this episode in the hopes of helping our community understand the full scope of our collective history.

Material for this post was taken from Maurine Boie, “A Study of Conflict and Accomodation in Negro-White Relations in the Twin Cities–based on Documentary Sources,” MA Thesis, (University of Minnesota, 1932); Chatwood Hall, “A Roman Holiday in Minneapolis,” The Crisis (October, 1931); Ann Juergens, “Lena Olive Smith : A Minnesota Civil Rights Pioneer.” William Mitchell Law Review 28, no. 1 (2001); Calvin F. Schmid. Social Saga of Two Cities; an Ecological and Statistical Study of Social Trends in Minneapolis and St. Paul. Minneapolis, Minn: Bureau of social research, the Minneapolis council of social agencies, 1937); Michele Norris, The Grace of Silence ( New York: Pantheon Books, 2010); Laurel Fritz and Greg Donofrio, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Lee Family Home, 46th and Columbus, National Park Service.

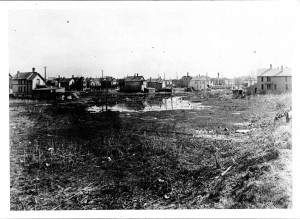

The map is from Schmid, “Social Saga” and the photograph is from the October, 1931 issue of The Crisis.