Today’s blogger is Heidi Heller, a senior history major at Augsburg College and an intern with the Historyapolis Project.

The Teamsters’ Strike–in July, 1934–is the best known labor conflict in the history of Minneapolis. This historic clash is now remembered as a turning point for labor relations in the city and the nation. Activists say that it was at this moment that Minneapolis became a union town.

But the Citizens’ Alliance–a notorious employers’ association known nationally for its ruthless suppression of labor organizers– did not capitulate in the wake of the Teamsters’ victory. And labor militancy intensified in the wake of the famous strike. The result was an intense period of labor unrest in Minneapolis, as workers and their employers struggled over the parameters of collective bargaining.

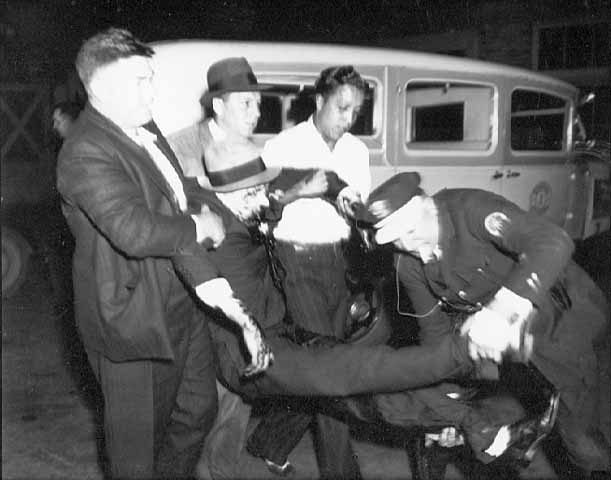

On this day in 1935–one year after the resolution of the Teamsters’ Strike–police and workers again clashed in the streets of Minneapolis. When dawn broke on September 12, two people were dead and 28 injured after a gun battle erupted between police and a crowd protesting the labor policies of the Flour City Ornamental Iron Company.

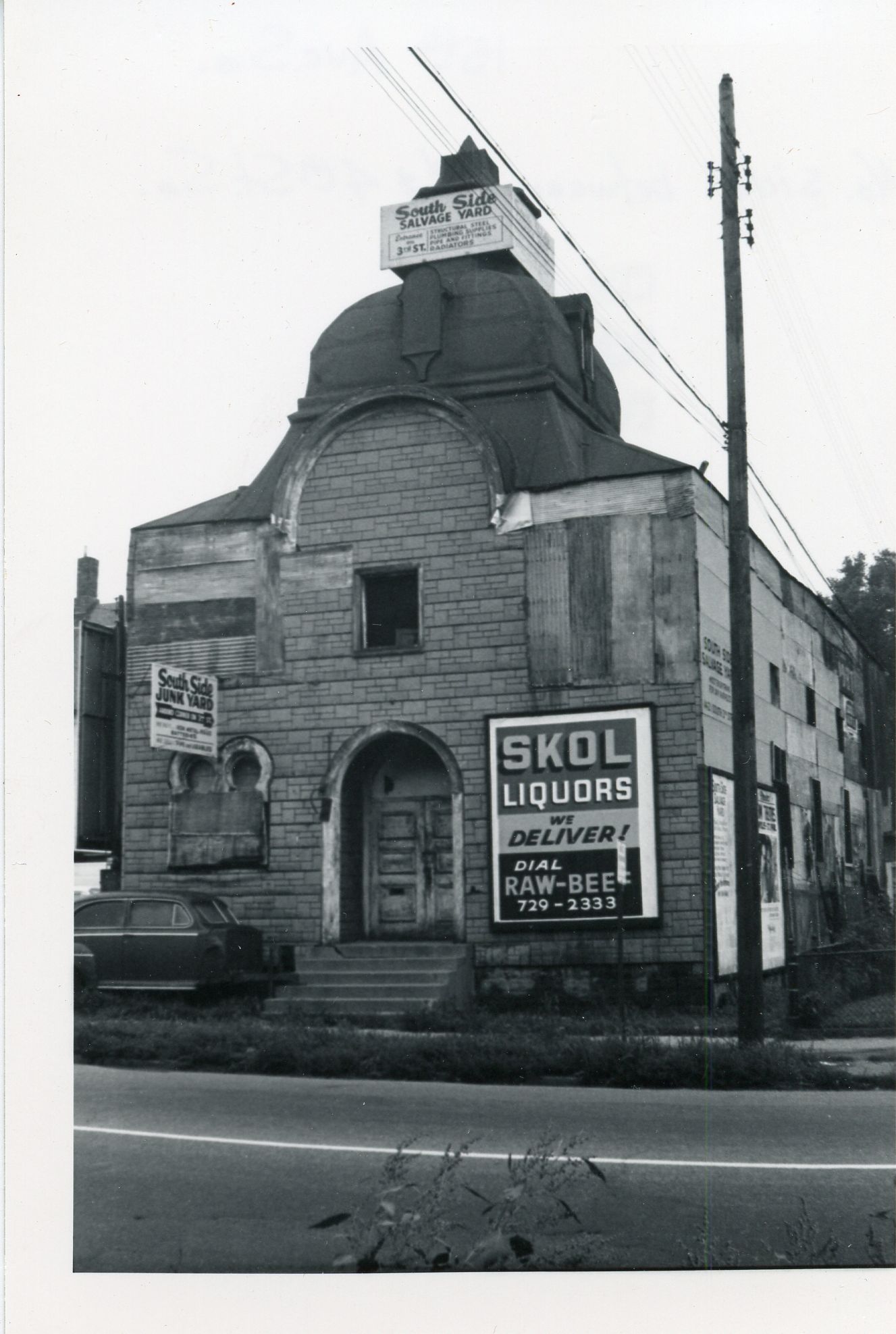

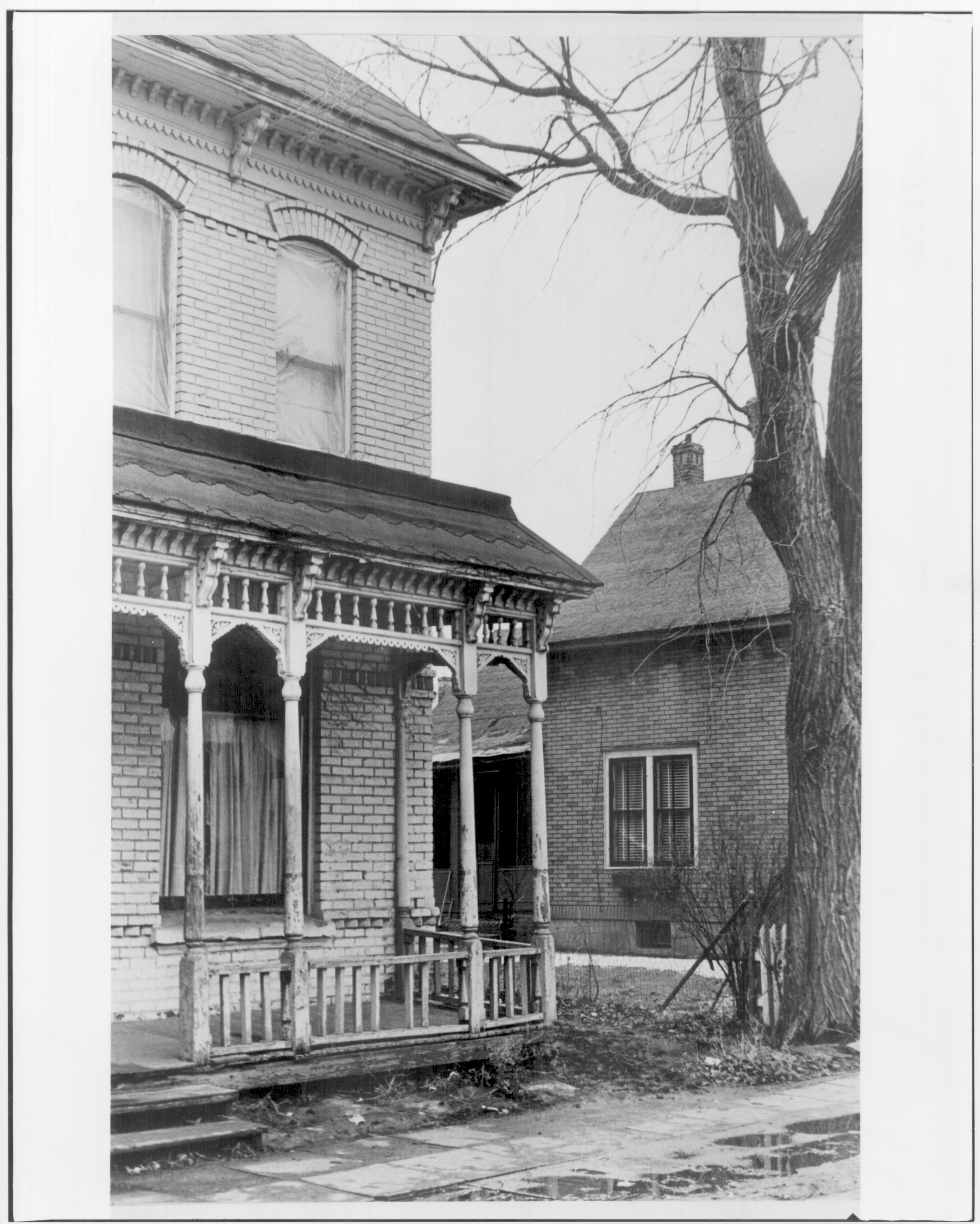

The Flour City Ornamental Iron Company had been a fixture in the working-class Seward neighborhood since 1901. The company had been non-union and owner, Walter Tetzlaff, an active member of the Citizen’s Alliance, worked hard to ensure it remained that way.

The Flour City Ornamental Iron Company after a clash between union organizers and police escalated into a gun battle on September 11, 1935. Note the broken windows. Image is from the Minnesota Historical Society.

In 1935–no doubt emboldened by the Teamsters’ victory–workers decided to challenge Tetzlaff. They organized collectively, forming a union that demanded a wage hike, a 40-hour work week and other workplace protections like a grievance and seniority system.

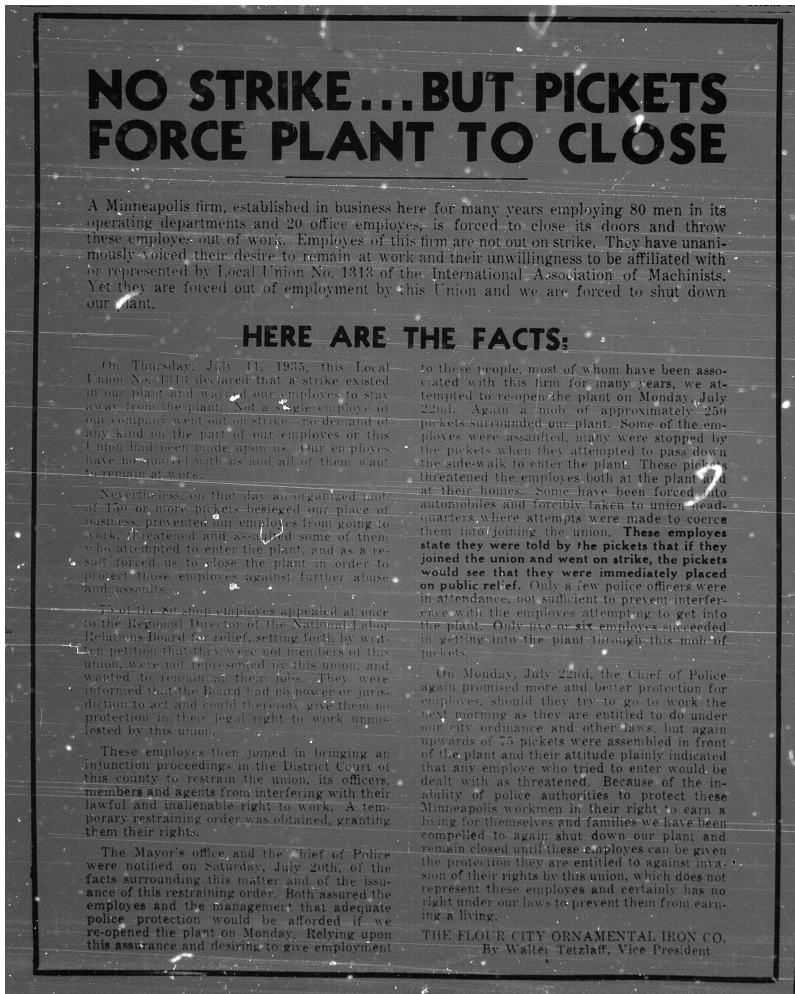

Tetzlaff rejected these demands. Workers responded by calling a strike, drawing support from other iron workers around Minneapolis, who also walked off the job. The factory managed to remain open, at least at first. Some employees remained loyal to their boss, even filing a restraining order against Union Local 1313. In July of 1935, Tetzlaff took out an ad in the Minneapolis Journal that called union supporters an “organized mob.” But as the strike dragged on, the factory was besieged. A hostile crowd threatened workers as they entered the building. Flour City was forced to close its doors.

The factory re-opened on July 25, after police escorted strike breakers into the building. By that night, union supporters had again surrounded the facility. The strike breakers were stoned. The factory went dark again.

Tetzlaff remained defiant, working with the Citizens’ Alliance to violate city ordinances and sneak workers into the facility. When the factory re-opened on September 9th –with a court order to house workers in the factory and under police protection–the union was ready. Protesters surrounded the building. The crowd threw rocks and shouted at the strike-breakers.

By the next night, September 10, the throng had swelled to 5000 people. The police used tear gas to drive protesters away. The next day, picketers were back in force. The police resorted again to tear gas, sending clouds of gas into the surrounding neighborhood and forcing bars and local businesses to close. But the protesters refused to leave. Police found themselves overwhelmed by wave after wave of union supporters.

The conflict came to a head just before midnight, when the crowd heard gun shots. A melee ensued. Hand-to-hand fighting broke out. Stones flew. Some protesters ran for cover, ducking down residential alleys and between houses.

Two hours later the battle was over. Two by-standers had been killed and 28 people had been injured. These casualties included a man who was shot in the arm as he sat on his back porch on 26th Avenue, another shot in the leg as he walked up the steps of his home on E. 26th Street and a woman who was hit in the face with a tear-gas bomb as she stepped off a streetcar. It was not clear who had done the shooting; police claimed that a group of picketers fired on them, union leaders denied the charges. Other claimed that Tetzlaff’s armed guards fired the shots.

Tetzlaff reached an agreement with strikers later in the month. The public largely forgot the battle in Seward. Flour City continued to operate until 1992.

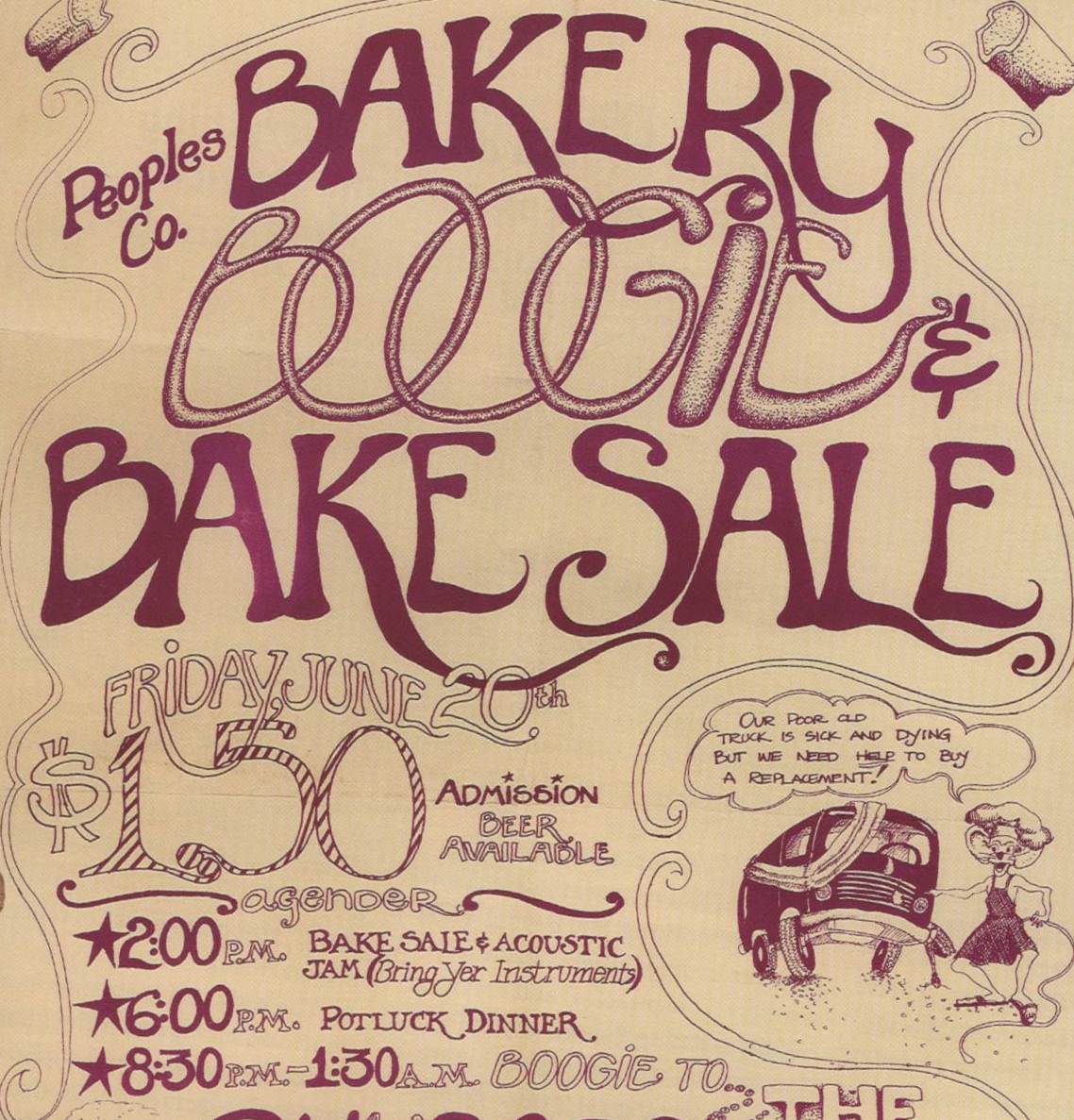

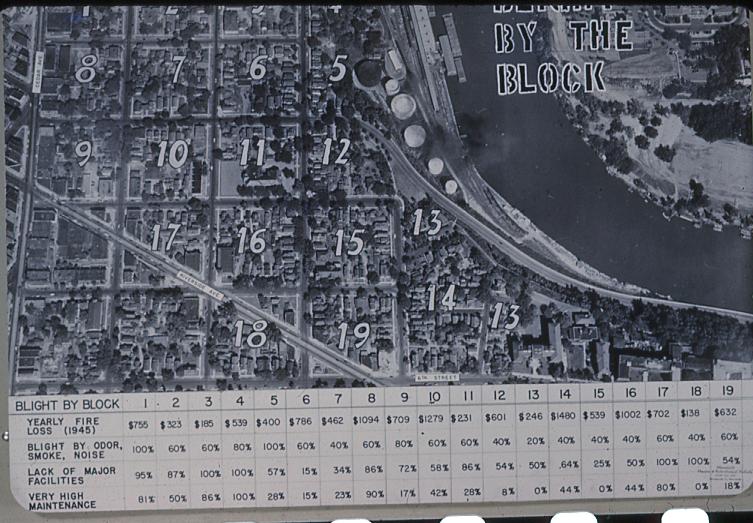

Sources: William Millikan, A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903-1947, Minnesota Historical Society, 2001. Iric Nathanson, “The Other Bloody Labor Disturbance,” Hennepin History Magazine, Summer 1995. “Two Dead, 30 Hurt in All Night Riot,” Lawrence Journal-World, September 12, 1935. Drew Shonka, “The 1935 Flour City Ornamental Iron Works Strike,” libcom.org https://libcom.org/history/1935-flour-city-ornamental-iron-works-strike-drew-shonka. Images are from the Minneapolis Journal, July 24, 1935 and the Minnesota Historical Society.