Today’s blogger is Heidi Heller. She is a senior history major at Augsburg College and an intern with the Historyapolis Project.

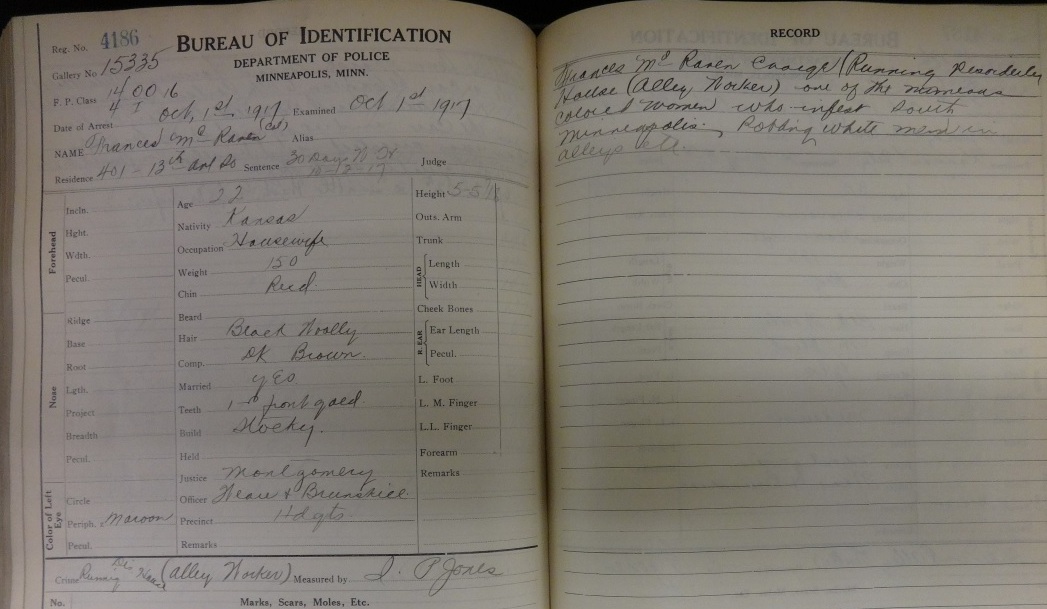

Today we have another excerpt from the Bertillon Ledgers in the Tower Archives at Minneapolis City Hall. This entry–which documents an arrest in 1917–illuminates the city’s campaign against prostitution in the run-up to World War I.

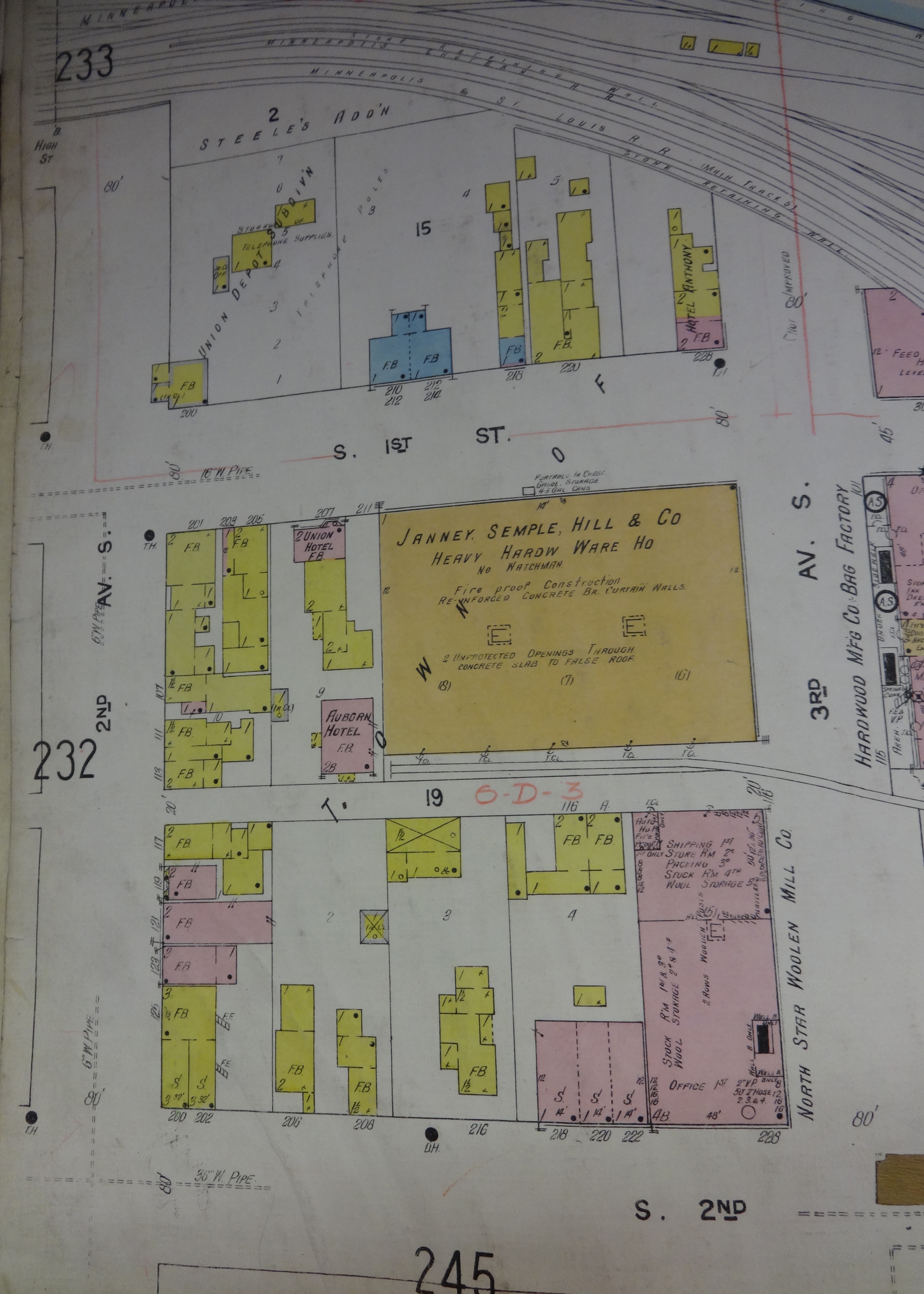

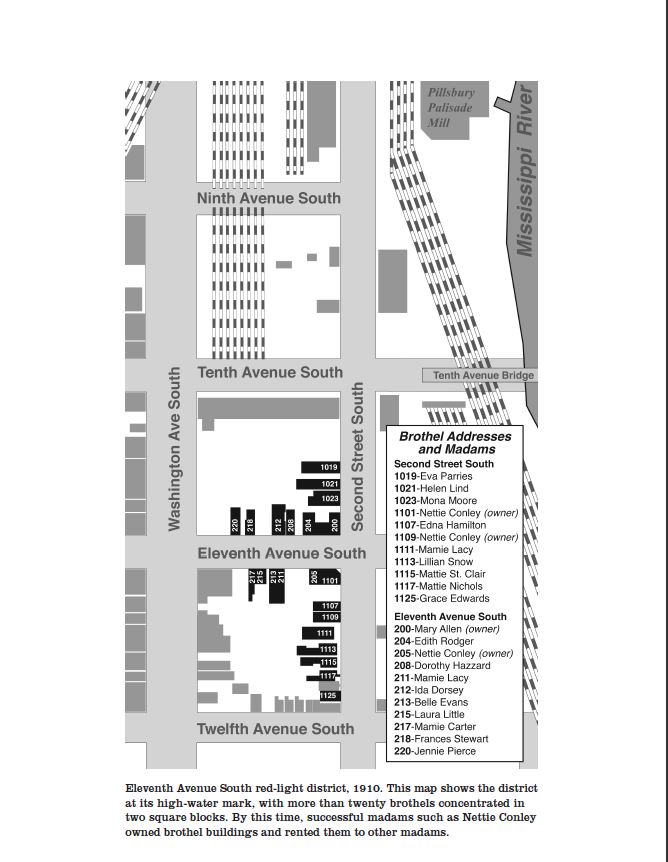

In 1910, city officials claimed victory over the social evil of prostitution when they shut down the red-light districts. Yet only one year later, the city’s Vice Commission issued a report that acknowledged that prostitution still represented a major problem for the city. The once segregated sex trade was now dispersed the throughout the city – into alleys, residential areas, hotels and saloons. Faced with the tasking of determining how to handle the growing city-wide problem of prostitution, the Commission debated the idea of once again allowing segregated areas of prostitution. Ultimately the Commission concluded “nothing is more certain than that segregation in Minneapolis has not, in fact, successfully segregated” prostitution.

To remedy this situation, Commissioners demanded increased police vigilance, encouraged citizens to report disorderly houses in their neighborhoods and insisted that police ban “vicious women” from saloons. They directed hotel keepers never to assign a room to two people of the opposite sex unless they were listed as husband and wife on a “bona fide register”; never to assign a room to a couple between 9pm and 6am; and never to provide a room to a couple that included a minor. Exceptions could be made only if the couple had “bona fide luggage”; permission from the police; or an affadavit from a “reputatable resident of the city” that they were husband and wife.

These measures did little to dampen the commercial sex trade. The industry continued to grow until 1917, when the federal government decided prostitution threatened wartime mobilization. Law enforcement in Minneapolis was happy to do its part for military preparedness and began rounding up the women they called “alley walkers.”

The Bertillon ledgers record scores of arrests. A disproportionate number involved “colored” women, who were sentenced to time in the workhouse. White women appear occasionally in the ledgers. But in the period between 1915 and 1919, it was primarily African-American women who were singled out for punishment. No doubt white women were also “alley workers.” But it seems that police did not see them as a pressing problem.

Police targeted women like Frances McRaven, who was arrested on October 1, 1917 for running a disorderly house and working as an “alley walker.” She was 22 years old, originally from Kansas and described as a housewife with a stocky build and one gold front tooth. She was also African American. According to the officer who described her crime and physique for the ledger, she “one of the numerous colored women who infest south Minneapolis, robbing white men in alleys, etc.”

Her arrest–and the many other ones like it–shed light on the changing nature of the sex industry in early twentieth century Minneapolis. But it also reveals the intense racism of the time. Prejudice isolated the city’s tightly-knit African-American community, making employment and affordable house difficult to find.

The city’s black community was small at the time of McRaven’s arrest. The Great Migration began in 1916, drawing millions of African Americans north with the promises of work and a better life. Few of these migrants would end up in Minneapolis. Between 1910 and 1920, the African-American community in Minneapolis grew from 2592 to 3927, an increase of 51.5 percent. In comparison, Detroit would see its African American population increase by 611.3 percent in the same period. Yet even this small population increase was viewed by many whites as a threat.

Negative racial attitudes prevented qualified African Americans from securing well paying jobs. In 1919, the Minneapolis Morning Tribune admitted that African-American women were “unable to secure the type of employment they are trained and fitted in every way to do.” Turned away from factories, department stores and telephone switchboards, many of these women were forced into the underground economy. Prostitution may have been the only way that many could survive.

Image from the Minneapolis City Archives. Material for this post is taken from Bertillon Ledgers, Tower Archives, Minneapolis City Hall; Report of the Vice Commission of Minneapolis, 1911; African Americans in Minneapolis: The People of Minnesota, David Vassar Taylor; “Survey for Benefit of Colored Women,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune¸ May 14, 1919.