Today’s guest blogger is Derek Waller, a senior from St. Olaf College who interned with the Historyapolis Project for his January term. A history major with a minor in gender studies, Waller explores the history of abortion in Minneapolis in this two-part post.

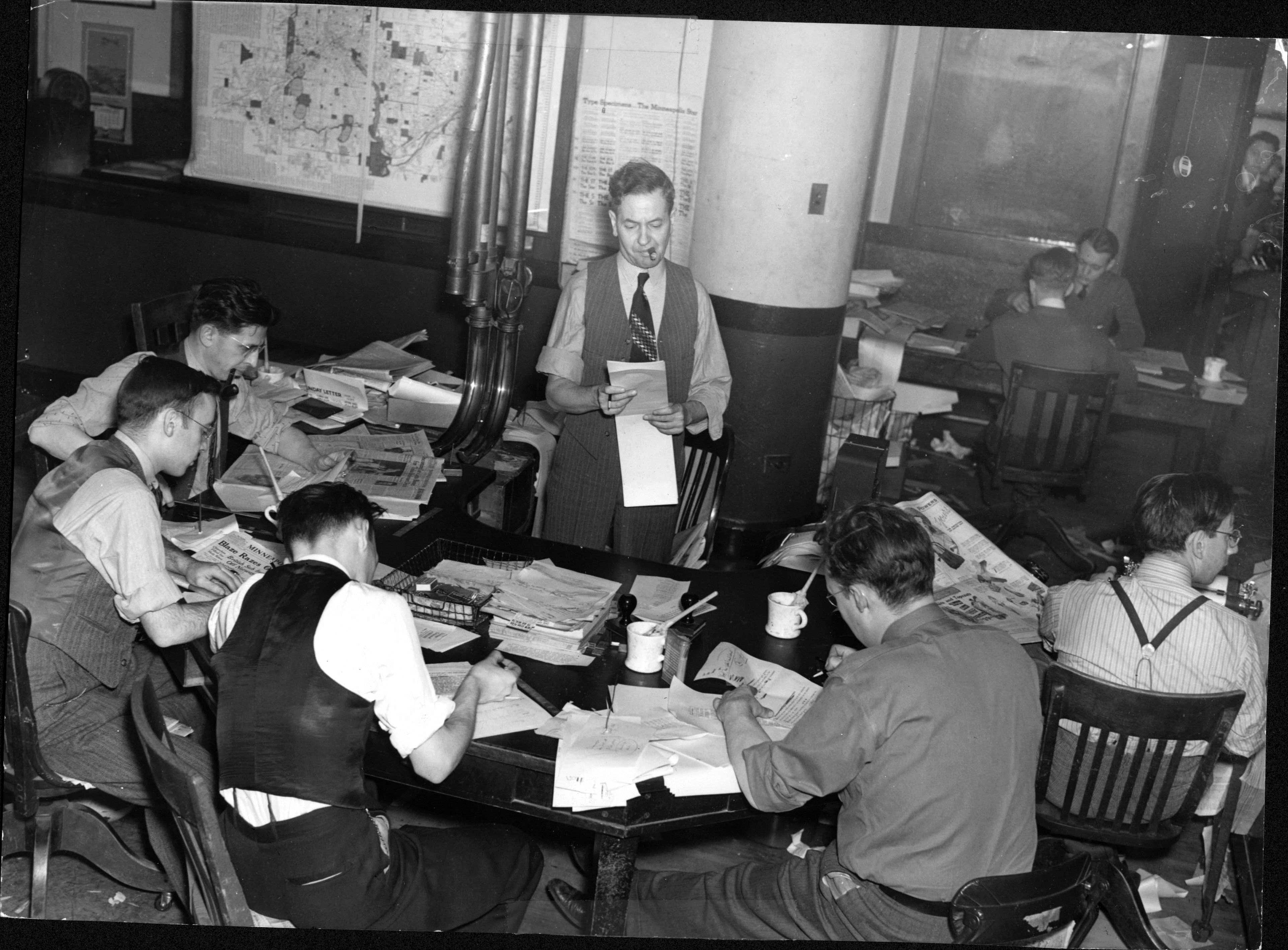

Shortly after Theresa Solie died from a botched abortion, the Minneapolis Tribune reported “2 Face Arraignment In Illegal Operation.” An inconspicuous piece on page 20, the article gave the names and addresses of the doctor and Martin Schmidt, reporting that the men were put on trial for performing the operation. The doctor, R.J.C. Brown, was an African-American who had operated a small practice in the Near North side for over a decade.

The average cost of an abortion in the 1930s was $67; Solie paid less than half that amount for her abortion. This probably indicates that Brown was catering to a less affluent group of women. We have no way to know whether he specialized in abortions or merely began to offer this service as a way for making up for the income that many physicians lost in the economic collapse of the Great Depression.

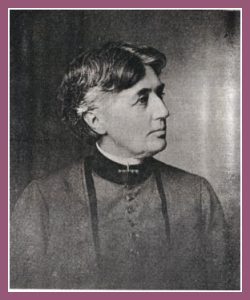

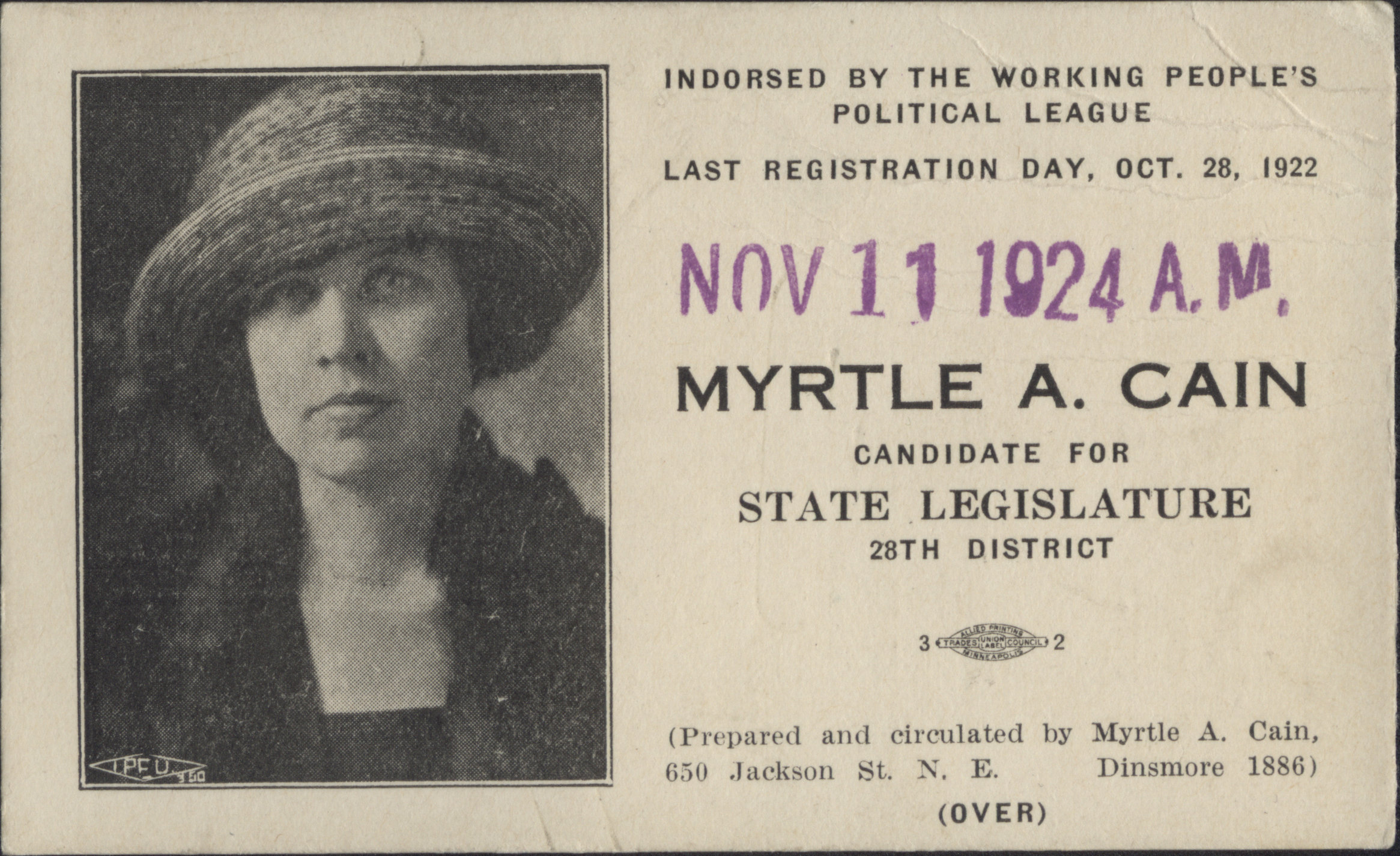

At the trial, Dr. Brown was represented by Lena Olive Smith, a prominent civil rights pioneer and Minnesota’s first female African-American attorney. Smith called on only two witnesses at the trial, Dorothy Johnson and Marie Schmidt. Dorothy, a friend of Theresa’s, testified that she was working as a prostitute, and Mrs. Schmidt’s testimony supported this claim. She said that Theresa was rarely home in the evening, and was unemployed. Mrs. Schmidt testified further that Theresa had received a package with medication to induce an abortion. However, the court refused to admit the pillbox as evidence, which was found among Theresa’s belongings. At every turn during the trial, the court ruled against Brown and Schmidt, admitting all the testimony for the prosecution while blocking evidence and testimony from the defense.

The court charged Brown and Schmidt with first degree manslaughter, sentencing both to prison. Schmidt was released after a year, while Brown served nearly 10 years; racism was almost certainly a factor in this outcome. Whether either of these men were responsible for Theresa’s death, we will likely never know. What does seem likely is that Theresa was a sex worker. No records of employment or testimony from an employer surfaced during the trial. Under desperate circumstances, Theresa had few connections in Minneapolis, and did not really have other options. Given the economic climate of 1938, many women ended up working as sex workers. Without the money or support system to raise a child, Theresa had to terminate her pregnancy. An unregulated and non-standardized practice in 1938, abortion was more likely to lead to death than it is today. The state found two men to blame for Theresa’s death, but did not recognize the material circumstances that caused it.

Thanks to William Mitchell law professor Ann Juergens, who shared this case and her other research on Lena Olive Smith with Historyapolis.