Today’s blogger is Heidi Heller, a senior history major at Augsburg College. One of the interns with the Historyapolis Project, she will be a regular presence here in 2014.

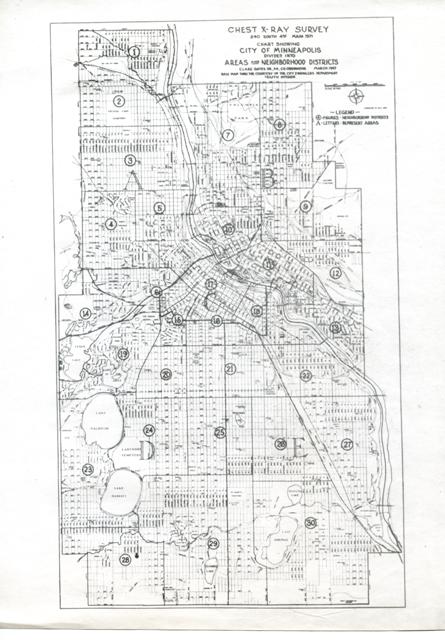

It’s map Monday. Today we’re highlighting another item from the tower archives at Minneapolis City Hall. At the dawn of the atomic age, the city created this map–dividing the community into numbered districts– as part of its new campaign against tuberculosis. During the summer of 1947, a mobile x-ray unit visited each of these sectors and performed chest x-rays on most Minneapolitans. The hope was that this miraculous new technology would help the city identify residents with active and contagious tuberculosis.

For Minneapolis and other cities around the country, tuberculosis had long presented a public health problem with few effective treatments; doctors had relied on sanatoriums, which prescribed fresh air, sunshine, rest and healthy eating for patients. This changed dramatically in the 1940s, which brought major breakthroughs in understandings of disease transmission as well as new treatment methods, including chemotherapy and antibiotics. This freed up new resources for TB detection efforts.

In Minneapolis, the idea of large scale city-wide survey to detect and treat individuals with contagious tuberculosis had been discussed since the late 1930s. But the high cost of screening equipment presented a major barrier to implementing such a program. In 1947, the city was offered new support for this effort from the federal government; the U.S. Public Health Service organized and supported a large-scale x-ray program for cities over 100,000 people. Thanks to this program–and with help from the Hennepin County Medical Society, Hennepin County Tuberculosis Association, the Minnesota State Cancer Society, the Hennepin County Chapter of the American Red Cross and the Minnesota Department of Health–the Minneapolis Health Department finally had the financial means to undertake a large scale TB chest x-ray survey.

An extensive educational campaign was launched to inform the citizens about the program and the need to be screened. Eleven mobile units with portable 70 mm photofluorographic units were used to screen 306,020 individuals over 15 years of age (in a city with a population of about 500,000). These initial screenings identified 5977 people who required follow-up exams. By the end of the summer, the survey had identified 150 to 200 people with active TB.

This photo is from the 1947 public health campaign to eradicate TB in Minneapolis. The majority of city residents recieved chest x-rays from mobile medical unit that summer. Photo is from the Minneapolis Municipal Archives, City Hall.

The U.S. Public Health Service continued the x-ray screening program until 1953; approximately 20 million people were examined during this time. The effort was discontinued after 6 years because the mobile units were costly to operate. Also, as effective preventive and treatment methods increased, tuberculosis infections rates dropped allowing public health programs to shift their focus to more pressing health concerns.

Image is from the Minneapolis City Archives. Material for this post is taken from J. Arthur Myers, Invited and Conquered: Historical Sketch of Tuberculosis in MN (St. Paul: Webb Publishing Company, 1949), “A Century of Notable Events in TB Control,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (Atlanta: CDC, 2000), William Roemmich, Francis J. Weber, Frank J. Hill and Lucille Amos ,“Preliminary Report on a Community-Wide Chest X-Ray Survey at Minneapolis, Minnesota,” Public Health Reports(1886-1970) 63, no. 40 (Oct. 1, 1948) 1285-1290.