Guest blogger today is Stewart Van Cleve, a graduate student in the program for Library and Information Science at St. Catherine University and the author of Land of 10,000 Loves: A History of Queer Minnesota. In this post, Stewart writes about Minnesota’s first statewide lesbian organization: the Lesbian Feminist Organizing Committee.

Since her 1980 election to the Minnesota Legislature, Representative Karen Clark has become a powerful voice in state politics. She and State Senator Scott Dibble helped lead the battle against a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage and, more recently, she became the House sponsor of Minnesota’s same-sex marriage bill, which Governor Mark Dayton signed into law last May. She looked on with her partner, Jacquelyn Zita, as Governor Dayton signed the bill, ending a fight for marriage equality that originated alongside Clark’s political career in the 1970s.

Clark’s foray into politics began four decades ago, when she participated in the landmark Sagaris Institute, a 1975 feminist conference held in Vermont. Though the Institute collapsed due to participant infighting and fears of FBI infiltration, Clark returned to Minnesota with inspiration, and she began organizing women from her home in the Powderhorn Park neighborhood. After a series of discussions with a diverse group of Minnesota women from around the state, she helped create Minnesota’s first statewide lesbian organization: the Lesbian Feminist Organizing Committee (LFOC). Though it only lasted for six years, the LFOC forged a local lesbian community that built the political infrastructure necessary for the immense cultural changes that transpired four decades later.

From the beginning, the LFOC called for radical change. “Lesbians are an oppressed minority,” the organization stated in its “Principles of Unity,” “…[and] we are working for the destruction of patriarchy, and for the development of a system in which there is an equitable distribution of power.” To help achieve the LFOC’s broader goals, Clark devised an innovative organizing strategy inspired by Marxist thought; she helped women create largely-autonomous “cells” that determined its own needs and objectives while simultaneously assisting the activities of the “mother organization,” which published newsletters and led organizing workshops for cell leaders. The structure proved extremely effective in responding to the myriad and often immediate needs of Minnesota lesbians. In an interview for Land of 10,000 Loves, one of the LFOC’s principal organizers, Janet Dahlem, remembered: “when people came to us with needs, we were able to respond and create a committee or a subgroup…we had a Lesbian Mother’s Legal Defense Fund because a women had lost her children to her heterosexual husband simply because she was a lesbian.” In addition to the Mother’s Defense Fund, the LFOC also led an organizing effort to curtail anti-lesbian hate crimes, which were ignored by both gay and mainstream news sources.

Simply by creating a political structure that gave women leadership roles, the LFOC helped destabilize male dominance in local politics, especially in south Minneapolis, where most members lived. The LFOC also helped Clark establish a mobilized base of dedicated volunteers who helped her first successful bid for elected office in 1980. Without the LFOC, Clark’s career, and thus the marriage equality legislation that defines it, would likely have not been possible.

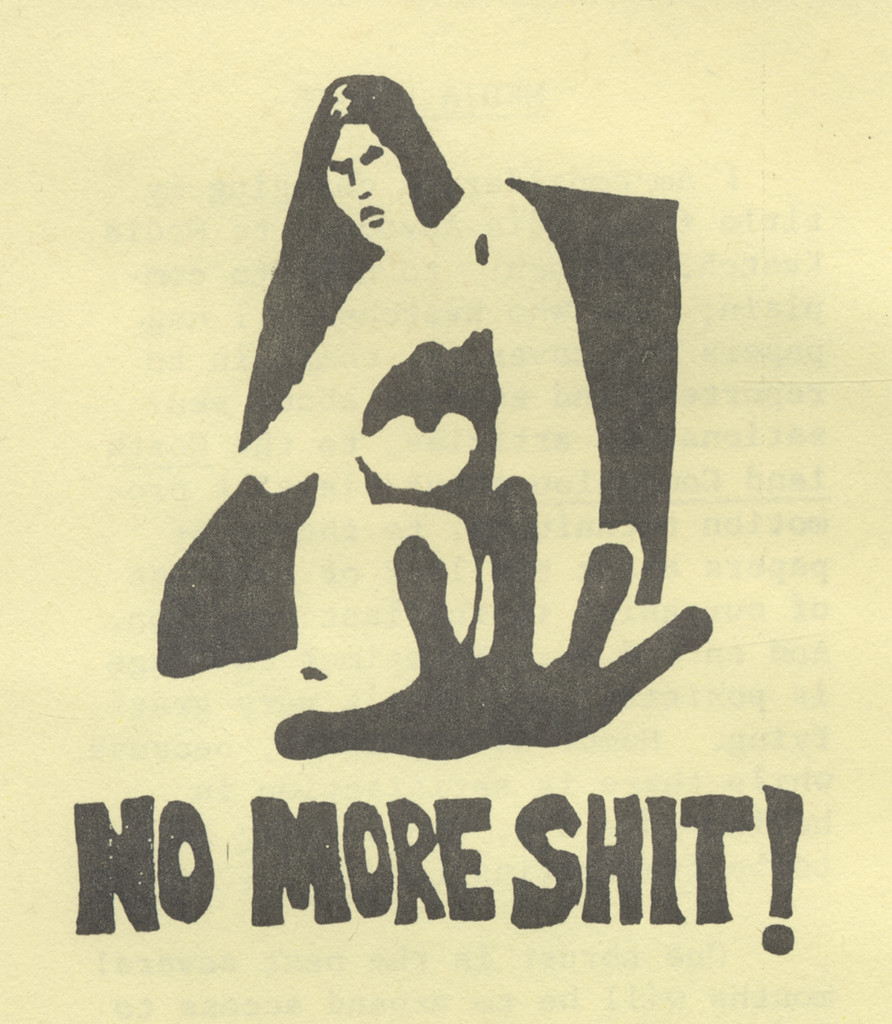

The image above is from the December 1978 newsletter of the Lesbian Feminist Organizing Committee. It comes to Historyapolis courtesy of the Lesbian Feminist Organizing Committee (LFOC) records, part of the Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies at the University of Minnesota.